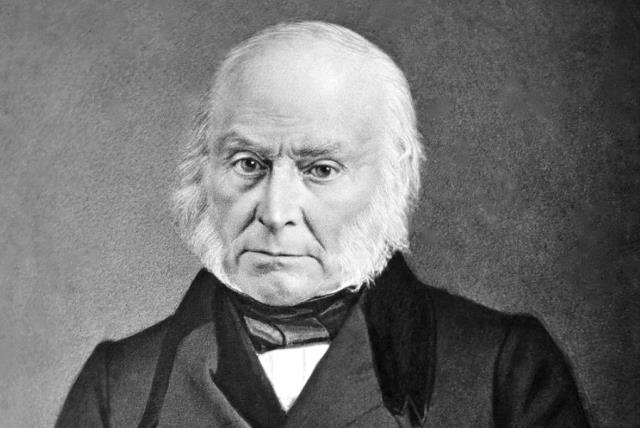

6. JOHN QUINCY ADAMS (the Cat's in the Cradle)

Born

Born: July 11, 1767, Braintree, Massachusetts

Died: February 23, 1848, Washington, DC

Term: March 4, 1825- March 4, 1829

Political Party: Democrat- Republican

Vice President: John Calhoun

First Lady: Louisa Johnson Adams

Before the Presidency: I think it’s safe to say that John Quincy Adams came from a political family given that his father was once President of the United States. Indeed, he was a child of the Revolution and, as a young lad, was said to have committed treason in defense of his father who, of course, was deeply involved with the Revolutionaries. Though too young to fight, he witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill with his mother.

Because he was the son of John Adams, that afforded the young John Quincy to see much of Europe as he would accompany the elder Adams to Paris among other places. With part of his schooling taking place in Paris, John Quincy would find himself very well educated by the time he was ready for adult life.

In some ways, his career started at age 14 when, already fluent in French, he accompanied emissary Francis Dana to St. Petersburg, Russia as an interpreter. A year later, he would rejoin his father at the Hague. Finally, he returned to the US in 1785 where he would attend Harvard for two years.

He more or less followed in his father’s footsteps and studied law, passing the bar in 1790. He was an admirer of Thomas Jefferson even though he was more in line with his father’s politics. Adams struggled in his early years as an attorney despite the fact that his father was now Vice President of the United States, but President Washington, maybe through the elder Adams, who undoubtedly loved his children, especially the hard working John Quincy, became aware of his linguistic skills and appointed him minister to the Netherlands. His political career had begun.

When his father became President, Adams was assigned as the Minister to Prussia where he remained until his father’s term expired. He returned to the US in 1801 and became involved with local politics, winning election to the Massachusetts State Senate.

And his star rose fast as he was appointed to the US Senate in 1803. He went against his Federalist party often, supporting President Jefferson on matters such as the Louisiana Purchase and the Embrago Act of 1807. This infuriated the party heads in Massachusetts and his days as a Senator were numbered. So were his days as a Federalist as he switched parties in 1808.

His political career was far from over. President Madison appointed Adams as the Minister to Russia where he became an ally of Czar Alexander, who he admired for standing up to Napoleon. It was, in fact, Adams who kept President Madison informed after Napoleon invaded Russia in 1812.

Adams would become involved with the peace negotiations with Britain that would end the War of 1812 and was one of the signers of the Treaty of Ghent in December 1814. Later, Madison would appoint Adams as Minister to the United Kingdom. He would return home in 1817 to become President Monroe’s Secretary of State. There, he was credited for writing what would become known as the Monroe Doctrine. He also oversaw the transfer of Spanish Florida to the United States in 1819.

President Monroe’s term was to end after the 1824 election, and it seemed as if Adams’ diplomatic career might be over, and it was.

But the career was about to have another chapter

Summary of offices held:

1794-1797: Minister to the Netherlands

1797-1801: Minister to Prussia

1802-1803: Member Massachusetts Senate

1803-1808: Senator from Massachusetts

1809-1814: Minister to Russia

1815-1817: Minister to the United Kingdom

1817-1825: Secretary of State

What was going on: the Erie Canal, the B&O railroad,

Scandals within the administration: None that we know of

Why he was a good President: He maintained good relations with most of the European nations, especially in terms of trade. And, even with all his flaws, no one could argue his integrity.

Why he was a bad President: He never did win the confidence of the Congress and his temperament probably wasn’t fitting for a sitting President.

What could have saved his Presidency: Not much really. The Congress was way too hostile at the time. Actually, under today’s standards, he could have even been impeached since the only crime you have to commit is to be disliked these days.

What could have destroyed his Presidency: As bad as his Presidency was, it could have been worse. Maybe he would have had no success in foreign affairs and, even with the debates over States rights (i.e., the right to enslave), no major violence occurred during his administration. A violent insurrection such as the events the led to the Civil War could have turned a bad administration into a notorious one.

Election of 1824: The rules were changing, at least in an unofficial sense. The previous three Presidents had served as Secretary of State at one time or another and it should have made Adams the favorite to be the next President.

But Adams didn’t really have the charisma of Jefferson or Monroe in particular and there were some firebrands waiting in the wings that also wanted to be President. By now, the Federalists were dead leaving the US with just one major political party. As such, they never really decided on a nominee.

So, John Quincy Adams was saddled with the pretty tough competition. Andrew Jackson was perhaps the most popular of the four major candidates and he was wildly popular in the South, but he wasn’t getting much traction in the North. The same went for the ambitious William Crawford, but, besides of an endorsement by Senator Martin Van Buren of New York, didn’t seem to be going anywhere either.

Then there was the Speaker of the House, one Henry Clay of Kentucky. Like Jackson, he was something of a war hero, but he was also a very capable legislator. It was he who came up with the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and was certainly well respected by the House members.

There was a convention and if they had it their way, Crawford would have been the nominee to run unopposed. But there were many factions within the party, and the states had their own ideas, thus, the general election ballot would feature six, count them, six, candidates.

Two of them, John Calhoun and Smith Thompson would bow out, leaving four candidates to duke it out. Calhoun ended up as the running mate of both Adams and Jackson while Crawford pegged Nathaniel Macon to run with him and Clay went with Nathan Sanford.

As it was, none of the candidates had the support of the entire country. Those in the South mistrusted Clay and Adams and the people in the North weren’t going to vote for Jackson or Crawford even if you put a gun to their heads.

So, for the second time in American History, the circus came to town. Jackson would win in the general election with a little more than 40% of the vote and have a plurality of electoral votes as well.

But there was just one problem. The Constitution stated that it went to the House when no candidate could gain a majority of electoral votes.

And so it was that the House, with their archaic rules of a majority of states as opposed to a majority of actual Representatives, would determine the next President of the United States, whether the American people liked it or not.

And they started with eliminating Clay, who, despite his legislative brilliance (He’s considered today as one of the most important non-Presidents in history), finished fourth and the House could only consider the top three candidates, Jackson, Adams, and Crawford.

Even that would prove to be controversial as the Clay supporters switched their votes to Adams, thus robbing Jackson of what he clearly thought was his Presidency. But we can get into that later when we review his Presidency.

In the meantime, there were cries of corrupt bargain as Adams would ultimately appoint Clay as his Secretary of State. Yes, Adams won the Presidency.

But he didn’t win much else.

First term: The election was behind him, but the support of the Congress was not. It didn’t help that Adams’s diplomatic skills were, shall we say blunt. It didn’t help that he was also opposed by his own Vice-President, John Calhoun. It wasn’t all bad though. The Erie Canal was completed during President Adams’ term, and it was during this term that his father, John Adams died, and he died knowing that his son was now the President of the United States. He had to have been proud.

Because of a hostile Congress, Adams wasn’t able to do a lot from a domestic standpoint. He had to settle for higher tariffs for example. He fared a little better with foreign relations, forging trade agreements with several European countries, but even that was a mixed bag. In the end, sad to say, John Quincy Adams would go down as one our least effective Presidents.

Election of 1828: By now the Democratic- Republican party had fractured into two factions and Martin Van Buren would soon establish what is known now as the Democratic party. Andrew Jackson, nominated by the Tennessee Legislature as early as 1825, would represent this faction while Adams represented the old Federalist platform (though, officially he was a Republican)

The issues were also pretty clear. States rights was the banner for the new Democrats (Or, really, an excuse to continue slavery) while the National Republicans, as they were called, took on a more Nationalistic approach.

It was an ugly election as things got quite personal. Though neither nominee campaigned personally, as was the norm, their supporters were out loaded for bear. Jackson was attacked by the Adams- backed press of having lived in sin with his wife and of multiple murders (Jackson was, in fact, a notorious duelist) while Adams, via the Jacksonian press, had the audacity to marry a foreigner (hey, at least she was white).

In the end, Jackson proved more popular, and he would win election easily, thus, Adams would face the same fate as the father as the then only Presidents to lose a re-election bid.

Post Presidency: Adams was somewhat bitter after the 1828 election and he refused to attend Jackson’s inauguration. This was probably the lowest point of John Quincy Adams’ life.

But he would bounce back. In 1830, there was a draft for him to run for Congress, and, despite family objections, he agreed. He won election, and he served with distinction from 1831 until his death in 1848. Though he usually voted with the minority (the nation was dominated by, let’s face it, some right wingers), he nonetheless proved to be on the right side of history, particularly as an anti-slavery advocate. He argued for the freedom of slave mutineers on the slave ship Amistad- and won.

Even his death was a bit spectacular as he was stricken on the House floor after vehemently speaking against decorating certain Army Officers involved in the Mexican-American war. He may have been a failed President but he wasn’t a failed man by any length of the imagination.

Odd notes: Adams was an avid skinny dipper

https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/...n-quincy-adams

He had a Niece that seduced all three of his sons

https://www.newenglandhistoricalsoci...-quincy-adams/

Anthony Hopkins played John Quincy Adams in the Steven Spielberg movie, Amistad.

Final Summary: Let’s face it, the poor guy never had a chance. The Congress refused to work with him, and he was not really forgiven for what many thought was a stolen election. He would fare better as a Congressman later but, alas, I can only rate him as a President, not as a legislator which I would give him a solid B for. Even as a diplomat, I’d rate him as better than average.

But as President, not so much.

Overall rating: D+

https://millercenter.org/president/jqadams

Hybrid Mode

Hybrid Mode