Chapter I: Go West, Young Man: Taming the Wild Frontier

Timeline: 1788 - 1803 (very approximately)

Frontier: another word you’ll hear associated with the West. Crossing the frontier. Pushing back the frontier. Exploring the frontier. Or, as in my example above, taming the frontier, wild or otherwise. Hell, they even called some of the trappers and hunters who made this place their own frontiersmen. Possibly women too. But what does it really mean? Frontier, I mean. Well, inevitably whenever I hear it I hear the voice of Captain James T. Kirk intoning that famous phrase on

Star Trek: “Space, the final frontier.” And so, mostly, it is. Space, that is. The final frontier. But for the people who moved out of the relative comfort and wealth of cities like New York, Philadelphia, Boston and Chicago, to seek a new life beyond what was then thought of as the civilised part of America, the frontier was something to be faced, something to be crossed, something to be dealt with.

A barrier. Not quite. But for me, this is what frontier has always meant. A demarcation line, beyond which lies, often, the unknown, or at least the very different. It’s like the coach driver says to Jonathan Harker at the beginning of Dracula: this far will I go, and no further. Although there is no physical frontier evident to Harker, he has arrived at one, and once he steps over it, passes it, and walks up to the dread count’s castle, he is essentially in a new land, a new world, a world of the unknown, the frightening, often the impossible. A wild frontier indeed.

What the hell is that doing here? Oh. Right.

What the hell is that doing here? Oh. Right.

Some call the ocean floor a new frontier, and so it is. Space, too, as mentioned above, is indeed a further frontier, though not to correct Kirk or Roddenberry, but it may not be the final one. Talk of digitisation of the human brain, the literal exploration of the mind, may end up being our final frontier. Or we may find that there is more beyond that, who knows? However, for the people of America, the West was certainly the frontier they had to deal with. A formidable, if not actually entirely physical barrier, a path that led to a new life, possibly - probably - a dangerous one, maybe even a short one. But just maybe a profitable one, and one that would change their future and their fortunes forever. After all, a frontier is only a frontier until it’s crossed, isn’t it?

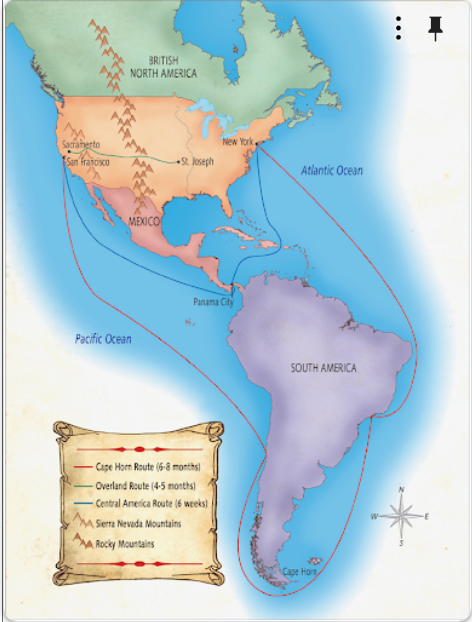

Imagine, then, the heady mix of excitement, anticipation, doubt and fear that must have beat in the hearts of these early pioneers as they loaded up all their valuables, their families, their entire lives onto a small wagon and headed West in search of gold, land, or just new opportunities. They would have known that the journey would be fraught with perils: far from the protective hand of their government, far from their friends, far from any kind of law enforcement, there was nobody to defend them from marauding Indians, or equally marauding bandits, both of whom roamed the prairie, searching for unwary travellers, unwelcome newcomers and plunder, be it material or personal. Many a hopeful journey would end up in shattered, overturned carts, blood, bones and brains spattered on the ground, stolen or butchered horses, and a life’s meagre possessions scattered across the arid desert floor.

So what was it that made these city folk leave the comfort and familiarity of their homes and strike out on a journey of several thousand miles, armed with little else than rifles and knives, with no real map or knowledge of their destination, across hostile territory, in the dim and vague hope of finding a new life?

Two things, really. The first was land. With so much unexplored and (to white men) available land up for grabs, a presidential decree promised an area of it completely free to anyone who would settle on it, cultivate it and basically colonise it. In a way, this perhaps mirrors the plantation of Ireland, especially Ulster, by Elizabeth I and James I, though that was more in an effort to disenfranchise and defang the Irish resistance to their rule. While the same could be said, in a way, of the Indians, pushing them off their native lands does not seem to have been initially the main idea behind this project; indeed, many tribes made treaties with the US Government which allowed them to remain on their lands, and held their holy places as forbidden to the settlers, provided the Indians reciprocated and did not attack the farms and holdings set up by the families who had moved there. Later, of course, as the Indian Wars took hold, all bets would be off and there would be incalculable suffering on both sides, resulting in the souring back home of the idea and romance of the new frontier, and eventually the subjugation and forced resettlement of the Indian tribes, an event which came to be commemorated by them as “the Trail of Tears”.

The other inducement? Oh yeah. Gold. Once gold was discovered in the hills ad mountains of the West, it precipitated a frenzy, a mad “dash for the cash” which we know as the Gold Rush, when anyone who had the resources, bravery and determination to do so headed west to try to make their fortune panning for gold, the dream being to set up a gold mine and become richer than astronauts. Unsurprisingly, the larger percentage of these ventures failed, and so you had people who had spent everything to come here, gambled it all on one unlikely throw of the dice, and inevitably lost. Like the Irish and others who had listened to tales of streets paved with gold, these people had literally believed these tales (or that they could make their own golden streets) and left bankrupt and with no future, unable to get home (perhaps unwilling to admit failure) they settled in the town in which they had come to make their fortune and tried to make a life for themselves and their families.

So towns grew up around settlements, some towns became mining towns, some ended up coining the phrase boom town, and later, when the gold had run out, ghost town, and some desperate people turned to crime to supplement their meagre income. Some excelled at this, and became successful and famous bank robbers, train robbers or guns for hire, while others failed miserably even at this and ended their days doing the hangman’s dance, dangling from a noose. Frontier justice was swift and brutal.

You could argue, I guess, that a lust for adventure stemming from boredom in the cities, failing fortunes back east which forced a man to reinvent himself in the west, or even sometimes a medical need for a literal change of scene also pushed people westward, but money and the opportunity to own land, own their own farm, must have been uppermost in most people’s minds when they decided to make that life-changing move.

Some, of course, had already headed out that way, for entirely different reasons.

Frontiersmen and Farmers: Take a Walk on the Wild Side

Since the successful ending of the American War of Independence, or Revolutionary War, tough hardened men had begun to move west, dissatisfied with the “easy living” in the cities of the east, and determined to strike out and explore this new frontier. With no support structure of any kind behind them, they had to be tough and resourceful, making most of their accoutrements themselves (no hardware shops in the wilderness!) and building their own shanty huts in which they would live while they hunted bear, buffalo and any other wild game they could eat or sell. A man had to be proficient with both gun and knife, as these could be the difference between survival and death, and there was no room for squeamishness. There was no blacksmith to tend to your horse if it lost a shoe, or treat it (or you) for illness. There was no way to preserve food, so everything had to be fresh; there could be no waste. You caught what you needed to make it through a winter, and no more.

Some frontiersmen built relationships with the local native tribes, realising that they were on their own and would need to get along with their neighbours if possible - you can’t fight a war on your own - and besides, the Indians could show them the territory, teach them where to go and where not to go, and by teaming up with the Indians, a trapper or hunter could avoid both stumbling on less friendly natives as well as keeping the risk of trespassing on holy ground minimal. Nothing angered an Indian more than if you went tramping heedlessly through the places in which he worshipped his gods, or which were sacred to his tribe. As a result of this burgeoning friendship and co-operation, there were many frontiersmen who, when the US Army began to sweep the tribes from the plains, rebelled against this wholesale destruction of the Indians and some even joined their allies, fighting against their own government, in effect “going native”.

Others went the opposite direction, seeing the native Indians as enemies, obstacles to their path to power, glory and riches, and believing the land belonged to whoever could win it, wrest it from the control of the other. Like most of us, these men were driven by one of the oldest motivators in humanity: greed. The abundant natural resources, the huge swathes of land, the massive opportunities available spoke to their desire to better themselves, and become more than they were. Many would become better than they were, rising in status and power as the wilderness that was the frontier shrunk and began to join up with the more civilised parts of the newly-born nation, as boundaries fell and barriers to both trade, commerce and expansion collapsed, and those who were in on the ground floor, so to speak, could, again, so to speak, write their own cheque.

On the other side of the coin were the settlers, the families. Those who would become known as homesteaders and pioneers, men who ventured out into the West in the hopes of bettering their lives, putting bad luck behind them and re-establishing their families and rewriting their story, women who stuck by their men and were determined to tough it out right alongside them, and their children, who would, if all went well, grow up to become the next generation of citizens of the newly-opened West; who would, in time, perhaps become leaders, status figures, perhaps even legends in this brave new world. Drawn by the promise of gold or just a new life, they bid the cities goodbye and loaded up all their… yeah, I’ve done this already, haven’t I? Well anyway, assuming they survived the dangerous journey, they would eventually found towns and cities, some of which would grow into the biggest and most famous in the USA, such as Phoenix, Houston, Seattle and of course San Francisco.

One of the main spurs that encouraged people to head west was the proclamation in 1862 by the government that anyone could have 160 acres of land, totally free of charge, anywhere in the West, provided they settled on and cultivated it. That’s a lot of land, and back east would not only cost a pretty penny but be likely out of the reach of any ordinary person, so here was a chance to almost literally put down roots, to claim an area of land that was yours by law, and which nobody could take from you, which you had to pay nobody for, and which, presumably, you could in time expand upon. And all you had to do to get it was leave your old life behind and strike out for these pastures new.

Oh, and survive the many hazards along the route to your promised land.

In the light of all this, and considering that the Republican government was essentially robbing this land from its rightful owners, the native Indian population, it’s almost funny, certainly ironic to read from the terms of the Treaty of Ghent (1814) which was agreed between the British Crown and the newly-formed United States after the War of 1812:

The United States, while intending never to acquire lands from the Indians otherwise than peaceably, and with their free consent, are fully determined, in that manner, progressively, and in proportion as their growing population may require, to reclaim from the state of nature, and to bring into cultivation every portion of the territory contained within their acknowledged boundaries. In thus providing for the support of millions of civilized beings, they will not violate any dictate of justice or of humanity; for they will not only give to the few thousand savages scattered over that territory an ample equivalent for any right they may surrender, but will always leave them the possession of lands more than they can cultivate, and more than adequate to their subsistence, comfort, and enjoyment, by cultivation.

Yeah. But we’ll come back to this much later, when it comes up in the timeline. Incidentally, I should also point out that, like some of my history journals and unlike others, though here I will be following a timeline of course, I will be deviating from it to write articles, profiles, small mini-histories of various events usually before they come up in the timeline. This will, I hope, prevent the journal getting too boring as a simple timeline progressing through the formation of the American West, and also prevent important figures or events all piling up together, as many will have taken place or lived around the same time.

Linear Mode

Linear Mode