The Central Pacific Big Four: Men with a Dream

The Transcontinental Railroad was the amalgamation of three separate railroads: the Union Pacific, the Western Pacific and the Central Pacific. One of the first men to envision the idea of a transcontinental railroad was of course an engineer, and well versed in building railroads. He would become one of the leading figures in the attempt to cross America with slats of iron and sleepers of wood, but he would sadly not live to see the fruition of his life’s dream.

Theodore Judah (1825 - 1863)

Theodore Judah (1825 - 1863)

To paraphrase Lyle Langley in The Simpsons episode “Marge vs the Monorail”, Judah would have been well qualified to have said “I’ve built railroads in New York, Sacramento and Marysville, and by gum it put them on the map!” He learned the trade from an early age, remembering the words of his father, a minister, that a life without a goal was a life wasted. He was certain he wanted to be an engineer, and also had taken a great interest in trains, but he wanted to ensure he left some sort of legacy behind, something that would mark his life as having meant something, and make his father proud. He surely succeeded, when, at age twenty-seven, he became a member of the American Society of Civil Engineers, and the next year went on to head the construction of the Sacramento Valley Railroad as its Chief Engineer.

Its president, Charles Lincoln Wilson, recruited him and he left New York to travel to California, where he presented his initial survey and report. Problems dogged the start of the project though, including the election of a new president and the position of vice president going to one William Tecumseh Sherman, and it was not until a year later, 1855, that work began on the railroad. Funding ran out though, and the proposed line to Marysville terminated instead at Folsom. Nevertheless, the Sacramento Valley Railroad became the first incorporated railroad in America, and would later be part of the Southern Pacific Railroad.

In 1859 he was nominated by the California Pacific Railroad Convention to lobby Washington for the proposed Pacific Railroad, but rumblings in the south as America prepared to descend into one of its darkest chapters in recent history distracted Congress, and he got no traction. Sorry. In fact, he was so almost evangelical about his pet project, describing it, somewhat in the same vein as that sarcastic member of congress, but with absolute conviction and not a hint of humour, as a gateway to Heaven, he became something of a laughing-stock in California, where people began to refer to him as “Crazy Judah”, but he would have the last laugh, and show them who was crazy.

II: Climb Every Mountain: The Rocky Barrier to the Railroad

While the idea of a transcontinental railroad had been in its infancy at the time of the Klondike Rush, the discovery of gold in Nevada reignited interest in a faster way to get to the lodes, and Judah was rehired by the Sacramento Valley to extend the railroad he had helped build, so that it now stretched from Folsom, its previous terminus, through the Sierra Mountains north of Lake Tahoe and on to the Nevada goldmines. It was while working on this that the engineer considered the major problem facing him concerning building what would become the Central Pacific Railroad, a route through those forbidding mountains.

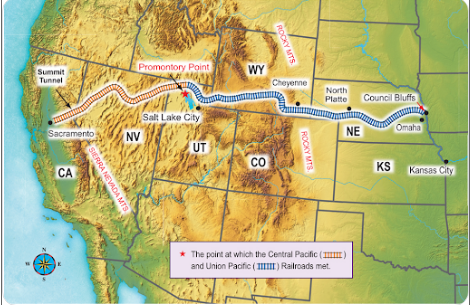

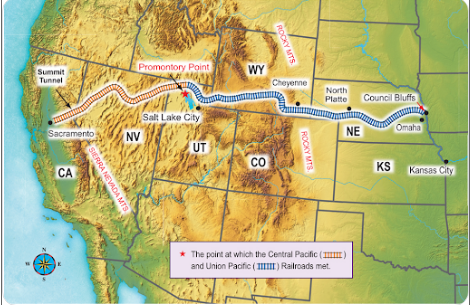

Judah’s experience in grading (the levelling of road before track could be laid), bridge-building and his almost supernatural knowledge of terrain - he could tell almost at a glance which ground was suitable for carrying rails and which was not - led him to go against popular belief that the best route for the railroad was across the flat Iowa plains to the Missouri River at Council Bluffs, then following the Platte River through the Rocky Mountains to the Great Salt Lake. Rails would then carry on westward from here towards the Sierras. This was to roughly parallel the Oregon and California Trails, which had been used for centuries.

But Judah found a shorter path through the Donner Pass and down the Truckee River to the Nevada mines. His plan was not without problems - the path he proposed entailed the rails (and the trains that would use them) climbing steep gradients and having to have massive (and expensive) tunnels bored into the bones of the mountains. Expensive, and dangerous work. In addition to this, construction would have to deal with massive snowfalls that would plunge down from the tops of the Sierras and threatened to bury them. Tapping private investors for the venture, Judah formed the Central Pacific Railroad Company in 1860, which did not impress Sacramento Valley Railroad, who fired him.

The Big Four: Making tracks for progress

Finding funds was not easy, and most of the wealthy San Francisco bankers laughed at him, as had Congress some years previous, but he managed to interest four other men, and these became the Central Pacific Big Four: they were Leland Stanford, future governor of California, wealthy hardware merchant Collis P. Huntington and his partner Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker, who had made his fortune in the gold rush, but not panhandling or mining: he had set up a shop to supply the miners and had quickly become rich off their labours. Coincidentally, it seems he lived as a child in the same district as Judah in Troy, New York, although there is no evidence the two men ever met.

The Big Four, in addition to the funding they brought to Judah’s fledgling enterprise, had political clout, having only recently formed the California Republican Party, who had had an early and landslide success with the election of their candidate, some guy called Lincoln, to the presidency. At last, “Crazy Judah” was in a position to make people listen; he had the ear (and fat wallets) of four very influential Republicans, who also had a more or less direct line to that of the President, and could smooth the way for any legislation pertaining to the building, and funding, of their new railroad venture.

With the secession of the southern states and the outbreak of the Civil War, the need for a reliable mode of transportation for troops, weapons and supplies became more urgent and the project was quickly greenlit, though in a time of war such things as material, fuel, even labour were scarce, as every resource the Union had was being poured into trying to win the war. Critics were loud in their dismissal of the idea, citing such problems as the winter snows high in the Donner Pass, the difficulty of transporting machinery around Cape Horn to Sacramento, the unlikelihood of the track being able to support the carriages and predictions they would sink into the ground, and an overall doubt that such an enterprise could manage any sort of profit at all for its investors.

Initially, it seemed some at least of these fears were well grounded, when Judah returned from his survey of the Donner Pass and glumly announced that he had seriously underestimated the cost of building the thing. The distance was longer than expected - 140 miles instead of 114 - and would require boring tunnels through three miles of solid granite, and he now estimated that his original budget would go over by fifty percent. This is not news any investor wants to hear, especially before the first hammer is even lifted, and in the face of so much opposition and lack of belief in the project.

Then, of course, there were, inevitably, the rivals. In the wake of the war, other companies had sprung up, eager to take advantage of the generous government grants, and controlled mostly by big San Francisco interests like Pacific Steamship Line and Well Fargo, all hostile to the Central Pacific Railroad and eager to crush it before it had a chance to get going. However when one of the Big Four, or The Associates, as they preferred to call themselves, was elected governor of San Francisco, he was able to appoint Judah to the House and Senate Railroad Committees, giving him the power to lobby in favour of his railroad project. Much bribery of course went on, and Judah even managed to sway one of their competitors, the San Francisco & San Jose Railroad, striking a deal which removed their opposition to the CPRR’s bid.

Charles Crocker (1822 - 1888)

Charles Crocker (1822 - 1888)

Born, as noted already, in Troy, New York, Crocker’s family moved to Indiana when he was fourteen, and he quickly became independent, proving a diligent worker and an intelligent man, the sort of entrepreneur America would turn out in droves around this time. He took advantage of the gold rush of 1849 to set up his own business, again as already mentioned, selling tools and hardware items to the miners who came to California in search of gold. While most of them went home poor, (or more likely, stayed where they were, unable to afford passage home) Crocker made huge profits and was able to answer the call when Theodore Judah asked for investors in his new Central Pacific Railroad. He set up Charles Crocker & Co., a subsidiary of the company dedicated to getting the railroad built, and he spent over two million dollars on snow ploughs to clear the tracks of snow, but the ice derailed both figuratively his efforts and literally his ploughs. Learning from his mistakes, like all good entrepreneurs, he had snow sheds constructed to protect the rails through the Sierra Nevadas from snow in the harsh winters. These stretched for sixty-five kilometres.

Leland Stanford (1824 - 1893)

Leland Stanford (1824 - 1893)

Another native of New York, Stanford was called to the bar in 1848, whereupon he moved to Wisconsin. Here he was nominated as the city’s district attorney, and in 1852 gold fever took him and he headed to California, where, rather like Charles Crocker, he resisted the pull of actual gold mining and instead opened a hardware store, making his fortune that way. He returned to New York in 1855 but was bored by the sedate pace of life there, a world away from the hurly-burly frontier life in California, and he moved back there, to Sacramento, the next year. Having invested in Judah’s Central Pacific Railroad, he was elected its president in 1861.

With the others of the Big Four, Stanford acquired control of the Southern Pacific and became its president too. He ran unsuccessfully for governor of California in 1859 but was triumphant in 1861, becoming the state’s first Republican governor. The first Central Pacific train was named in his honour.

Collis P. Huntington (1821 - 1900)

Collis P. Huntington (1821 - 1900)

The only one of the Big Four, or five if you include Judah, not to have been born in New York, Huntington was a native of Connecticut, and was also the only one of them all to see the twentieth century. Like the others, he too made his money in the gold rush, but through commerce in a venture he set up with Mark Hopkins, who would join him as the last of the Big Four. He would in fact in time oust Leland Stanford from the presidency, and was well known for providing generous bribes and kickbacks to politicians and businessmen, earning himself the title of “the most hated man in railroad”. He would, however, also be credited with many projects to educate black children and adults after the end of the Civil War.

Mark Hopkins (1813 - 1878)

Mark Hopkins (1813 - 1878)

Hopkins arrived in California in 1849, just as the gold rush reached its height, and established a store in Placerville, but had little luck with that and relocated to Sacramento. It was, however, after meeting Collis P. Huntington that he had real success, the two men becoming fast friends and partners, a relationship they took to the formation of Theodore Judah’s Central Pacific Railroad, of which Hopkins became treasurer. His opinion was highly prized by Huntington, and he was trusted as a true and decent man. He was the eldest of the Big Four, and perhaps appropriately died while aboard a company train in 1878.

Before war broke out, southern congressmen had lobbied to have the railroad cross the Mississippi at Memphis, and then turn west through the southwestern territories, running through Texas and New Mexico, hoping that the new towns which were expected to spring up along the route would all be southern towns, and thus in favour, as was all of the south, of slavery. At the outset of the war though, all southern representatives had abandoned the capitol, and therefore there was nobody to oppose the route favoured by what were now the Union states, which was Judah’s proposed route, and which now got the green light. Naturally, construction was delayed due to the war, but a decision had been made, which in Washington is saying a lot.

The Pacific Railroad Acts

Congress passed a series of acts in 1862, unencumbered by opposition from the south, promoting the construction of the transcontinental railroad, otherwise known as the Pacific Railroad, and authorising funds through the issuing of government bonds and land grants to railroad companies. The whole thing proceeded under the auspices of the War Department, and the original rather long-winded act was titled

An Act to aid in the construction of a railroad and telegraph line from the Missouri river to the Pacific ocean, and to secure to the government the use of the same for postal, military, and other purposes. Right. The two companies to benefit from these bonds and grants, and thereby establish a monopoly on rail travel in the USA, were the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific Railroads. We’ll be looking into the Union Pacific later; right now we’re concerned with the other one.

The companies were granted contiguous right of way for their railroads throughout the United States, including all public land within thirty metres on either side of the track. They were given government authority to construct their railroads between the eastern side of the Missouri River, at Council Bluffs, Iowa and the navigable waters of the Sacramento River, thirty-year bonds which would guarantee a loan payment to them for each section of track as it was completed, in return for a lien on the section, to be returned when the loans fell due and were paid.

From 1850 to 1871 the railroads were granted the sum total of land bigger in area than the great state of Texas, approximately 175 million acres, and were allowed, under the terms of the Railroad Acts, to sell some of that land to incoming settlers, who paid a handsome price for land close to the railways, desiring the convenience of nearby transport for cattle and/or goods. It was clear that though the railroad would eventually be a huge moneyspinner, it might take months or even years before the investors began to see appreciable profit, and so they took every opportunity to make cash for themselves, including double-dealing, controlling the contracts tendered for the various subsidiary projects, and keeping wages down despite the dangerous, often fatal nature of the labour.

They also built largely superfluous sections of railroad, building where their partner in the venture, Union Pacific, were also laying track, knowing that their sections would not be used as this was to be one integrated network, but determined to be paid, as they were, per mile of track, whether it was used or not. The passing of the Homestead Acts, as detailed in a previous article, encouraged settlers to head west, and ensured the newly-formed railroad would not be short of customers, thereby swelling their profits even more.

Having been scandalised by the money-grabbing and deceitful tactics of his investors (at one point, their mapmakers showed the Sierra Mountains to be twenty-three miles east of where they were, just so they could get the bonus for building on mountainous terrain, when in fact the land there was flat and even) and realising that they shared his dream but only for what they could get out of it, enriching themselves as much as possible, Theodore Judah decided to buy out the Big Four, and assume control of the project. He made the trip back to New York to raise the necessary capital, but tragedy struck when he contracted yellow fever and died at the age of thirty-eight. The irony is that he had to go, as Asa Whitney had complained of twenty years ago, via Panama to get back to New York, and it is believed it was while crossing the Isthmus of Panama that he fell victim to the disease which claimed his life shortly after he arrived back in the city of his birth. Had Congress listened to the likes of Whitney and Henry Carver earlier, the transcontinental railroad might already have been in service by that time, and he would not have needed to have gone near Panama.

He was, of course, never forgotten, having a street in San Francisco named after him, and memorial plaques installed in Folsom and Sacramento. Schools bore his name, and naturally, one of the first of the CPRR’s locomotives was named in his honour. Most impressive of all, his name was given to a high mountain adjacent to Donner’s Pass, which he had originally surveyed and which became part of the route for the Central Pacific railroad. Mount Judah stands over 8,000 feet high, towering over Placer County, as indeed Judah himself loomed large over the dream of a transcontinental railroad that would link up all of America.

Linear Mode

Linear Mode