Brother, Where You Bound? Finding Direction and Taming the Wind

Brother, Where You Bound? Finding Direction and Taming the Wind

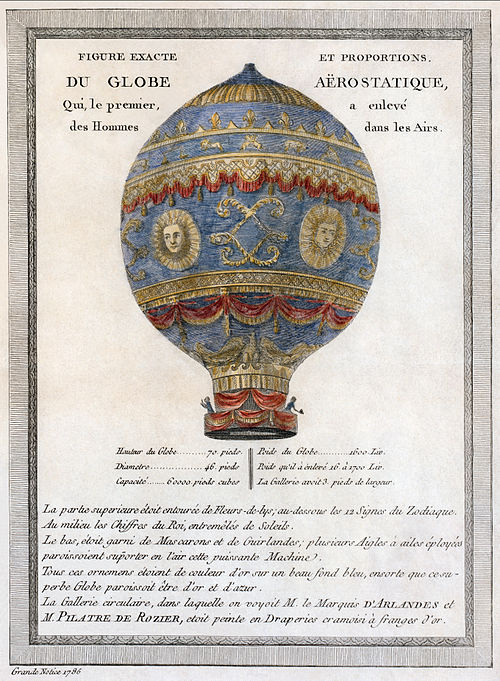

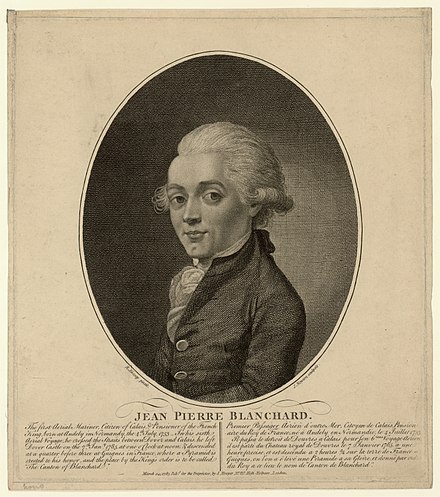

Flying in balloons was all well and good, and as James Onedin once remarked, the wind blows free for any man. But that was the trouble: the wind tended to obey no rules but its own, and any intrepid balloonist who ventured up into the big blue was at its mercy. There was originally no way to steer a balloon, and so they literally drifted on the wind, perhaps going the way the pilot intended, perhaps not: witness Blanchard’s original plan to fly northeast to La Vilette in Paris but being blown by the wind across the Seine instead westward towards Billancourt. In that case, it surely didn’t necessarily matter which way he went, once the flight was successful. But as ballooning became more widespread and more popular, people wanted to choose the direction in which they flew, and to make sure they went that way.

The only possible way to achieve this was to be able to control the trajectory of the balloon, and to this end people like Henri Giffard (1825-1882) began to experiment with steam engines, but these proved too heavy to be effective, while German Paul Haenlin (1835-1905) did fly in a dirigible powered by an internal combustion engine, and utilising a propellor driven by the engine. His experiments were limited to tethered flight though, due to a shortage of capital. Lack of funds also proved to be the stumbling block which prevented Charles Renard (1847-1905) and Arthur Krebs (1850-1935) from furthering their work on

La France, the first powered dirigible, or any aircraft of any sort, including balloons, to return to its place of take-off, after a 23-minute flight around the Eiffel Tower.

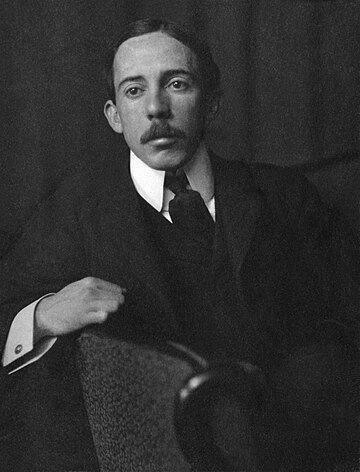

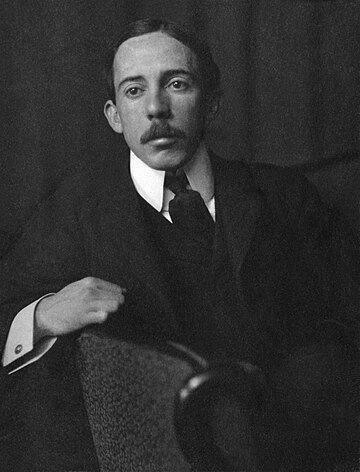

Alberto Santos-Dumont (1873-1932)

Alberto Santos-Dumont (1873-1932)

Often cited by his countrymen as the father of aviation, this Brazilian engineer managed to conduct the first ever manned and untethered flight of a powered balloon. Heir to the huge Santos-Dumont coffee empire, Alberto moved with his parents to France when his father was paralysed after falling from a horse. Seeking treatment in Europe they arrived in Paris, where young Alberto fell in love with the idea of ballooning, and thereafter dedicated his life to the pursuit of aviation. He was heavily involved in heavier-than-air flight too, but here we will concern ourselves only with his ballooning and dirigible exploits.

After several flights in balloons in Paris, Santos-Dumont decided to build his own, and had a purpose-built factory erected. His efforts bore fruit, as he won the Deutsche de la Muerthe Prize for being the first to make it from the Parc Saint Cloud to the Eiffel Tower and back, though in the run-up to the attempt he did lose one balloon when it started to sink due to a loss of hydrogen, leaving him stranded on the side of a hotel. When he won the prize, to his credit, already being very wealthy he donated the money to Paris’s poor. This, along with his fame as a balloonist and love for the city, made him a favourite among Parisians, and they would often watch him float down the streets in his balloon, on his way to lunch in some fashionable cafe.

Like Blanchard before him, Santos-Dumont soon looked to America to further his reputation, and to enhance the interest in ballooning, when he entered his balloon in a competition in St. Louis, however though he did get to meet President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House, his ambitions were thwarted as his balloon was damaged - sabotage was suspected but could not be proven - and he returned to Paris, where he inadvertently contributed to the invention of the wristwatch, after he pointed out to Louis Cartier how difficult it was to check one’s pocket watch during flight.

And here is where we will leave our friend from Brazil for now, but he does figure prominently in the later history of early aviation, and we will return to him in due course.

Ballooning Outside France

Though it can’t be denied that France was both the birthplace and the mecca of ballooning, and that anyone interested in the sport came there to test, fly or design their balloons, the interest had spread and there were balloonists in England, Scotland, Ireland and elsewhere around the same time that the French were taking all the headlines.

BRITAIN

Naturally, England was the next biggest hotbed of ballooning. We have already related how Jean-Pierre Blanchard moved there to conduct his own tests and flights, but essentially these were still French-driven. However it was a Scot, James Tylter, who made the first true British attempt, flying a modest 350 feet for ten minutes on August 27 1874, a month after Jacques Charles and the Robert Brothers had made their historic flight, and, amazingly, exactly one year to the day after their first-ever hydrogen balloon met its fate at the hands of angry peasants in a French village.

Vincenzo Lunardi (1754-1806)

Vincenzo Lunardi (1754-1806)

Arriving in London as the attache to the Neapolitan Ambassador, Italian aeronaut Vincenzo *Vincent” Lunardi tackled the doubt and suspicion among Englishmen about ballooning, demonstrating (in company with a cat, a dog and a bird in a cage - what is it with these people and animal passengers?) that balloons could fly safely. He flew 24 miles in a hydrogen-fuelled balloon on September 15 1784, one month after the Scot Tytler had made his ascent. The successful flight made him a celebrated figure in England, though Doctor Johnson was less impressed: “In amusement, mere amusement, I am afraid it must end, for I do not find that its course can be directed so as that it should serve any purposes of communication; and it can give no new intelligence of the state of the air at different heights, till they have ascended above the height of mountains, which they seem never likely to do”

Lunardi then flew again in June 1875, this time inviting a woman on board, making Leticia Ann Sage the first Englishwoman to fly, and proving the second time a man, intended to fly as a passenger, stepped down in favour of the lady. This time it was Colonel Hastings who had to gallantly relinquish his place in the balloon as it would have been too heavy with all three of them, while Count Jean-Baptiste de Laurencin had been the gentleman a year earlier in Lyon, who gave up his seat to Elisabeth Thible. Chivalry, huh? Wouldn’t happen today! Not so chivalrous, however, was the farmer in whose field Lunardi’s balloon landed, ruining his crops, who, despite the presence of a woman, threatened them both till they were rescued.

The Lunardi ballooning tour then moved on to Liverpool before crossing the northern border and heading for Scotland, where he gave demonstrations in Glasgow and Edinburgh, proving as much of a hit here as he had been in England. These things are of course though ever fraught with danger, and the threat of death, and just before Christmas 1785 Lunardi was blown by bad weather into the North Sea, where he remained for some time before being rescued. Perhaps ironically, his take-off spot had been from the local hospital! This experience led him to invent and develop a miniature lifeboat for the victims of shipwrecks.

The next year, disaster struck again when, in Newcastle, spilled vitriol (acid) caused the men holding down Lunardi’s balloon to scatter, and one of them became entangled in the ropes as it ascended ahead of time. Dragged up into the air, he fell from a height and died. Lunardi decided it was time to bid farewell to the shores of merry old England, and struck out for pastures new. He travelled to Portugal, Spain and Italy, where he conducted the first ever ascent over the dormant Mount Vesuvius.

Two other attempts in England ended in disaster, with one, a Mr. Arnold, coming down in the River Thames, while the appropriately-named Major John Money, attempting to raise funds for a hospital, was blown, like Lunardi, into the North Sea and, like the Italian pioneer, only survived by being rescued by a small boat.

James Sadler (1753-1828)

James Sadler (1753-1828)

The first English balloonist though was James Sadler, a pastry cook by trade, and he made his first ascent only two months after James Tytler, however his flight achieved a height of ten times as high as his Scottish contemporary, over a distance of six miles. He attempted to emulate Jean-Pierre Blanchard in 1875 but was unable to cross the Channel, landing instead in the Thames, and he was another who seemed to prefer the company of the feline sort, as a cat (not sure if it was his pet or not) accompanied him on one of his later flights. Another to realise the dangers inherent in his chosen sport, Sadler was badly injured after having been thrown from his balloon and dragged along for some distance before the balloon disengaged and flew off without him. A further trauma ensued in 1824 when his son died in a ballooning accident.

During his time as a balloonist, Sadler set a speed record by flying over a hundred miles in an hour in the teeth of a gale, attempted to cross the Irish sea from Ireland in 1812 and almost died in the effort, and was asked to travel to London in 1815 to open the Jubilee celebrations for that year. Despite being a celebrity in his own time, Sadler’s low social status meant that he was virtually ignored by history, as men who were rich and noble took all the plaudits, but nobody can take from him the title of having been the first Englishman to fly in a balloon on his home soil.

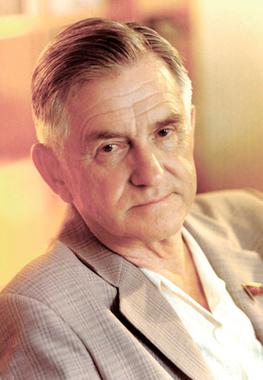

Charles Green (1785-1870)

Charles Green (1785-1870)

Undoubtedly the most famous English balloonist, Green was another man of humble origins, being the son of a fruit grocer, but while James Sadler is all but airbrushed from the history of ballooning Green is celebrated. He undertook both the longest flight and the one with the most passengers, the latter amounting to at one point eleven people not including himself, so twelve in one balloon, the great Nassau Balloon he built himself, and the former an epic journey from England to Germany, covering a distance of over 500 miles in just over eighteen hours. Tragedy again struck in 1837, though not for Green: one of his passengers, a painter called Robert Cocking, decided to test a parachute he had made by, well, jumping out of the balloon. Obviously the QA Department were less than effective. Unsurprisingly, he died on impact. Should have stuck to painting.

Green certainly flew the highest of the balloonists at the time, reaching at one point in 1838 the ceiling of almost five miles, and he seems to have been victim of quite some misfortune, having at one point to take refuge on the balloon itself when sabotage or vandalism caused the basket or car to separate from the balloon, the ensuing journey causing him and his passenger many injuries. For some reason he decided to take a deaf and dumb guy up in a storm (!) and in 1841 was almost thrown out of the balloon along with his passenger. He was responsible for some major strides forward in the technology, including the invention of a guide rope which allowed the balloon to be steered, and the discovery that coal-gas could be used in place of hydrogen, the latter being very expensive to use and time-consuming to inflate balloons with. On his retirement from ballooning in 1852 he had made over 500 ascents and flights.

IRELAND (Yes, Ireland! Don't look so surprised!*)

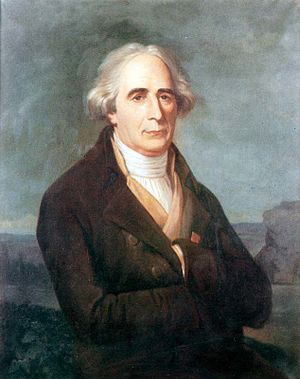

Richard Crosbie (1755-1824)

Richard Crosbie (1755-1824)

The first Irishman to fly, Crosbie emulated his peers by sending balloons piloted by animals, notably a cat, which had to be rescued from where it landed near the Isle of Man (hey, at least it wasn't the Isle of Dogs!), before attempting the flight himself. No doubt the cat wished him luck! And luck he did indeed have. On January 15 1875 he rose from Ranelagh Gardens in Dublin in a hydrogen balloon he called his “aeronautic chariot” or “flying barge” and flew to Clontarf, a distance of about six miles. Obviously a showman, like every other balloonist, Crosbie’s ascent was witnessed by an excited crowd of onlookers, his mode of dress described as “a robe of oiled silk, lined with white fur, his waistcoat and breeches in one, of white satin quilted, and morocco boots, and a montero cap of leopard skin.”

His intention had been to cross the Irish Sea, but due to the early fall of darkness he decided instead to land at Clontarf. However he did try again six months later, this time making it halfway across before having to be rescued by a barge which had been shadowing him. The Lord Mayor of Dublin was not best pleased, having instigated a ban on ballooning as too many people were wasting time staring up at the sky instead of working. Spoilsport.

*Hell, I know I was!

USA

Thaddeus S.C. Lowe (1832-1913)

Thaddeus S.C. Lowe (1832-1913)

One of the foremost balloonists of the US, Lowe’s career would be interrupted by the American Civil War (see further) in which he would serve as the very first ever observational balloon pilot, helping the Union war effort tremendously, despite receiving little or no recognition for his efforts. Coming from pioneer stock, Lowe was a respected politician and scientist, and developed an abiding interest in and love for the new sport of aviation, building his own balloons and even inventing a system whereby hydrogen could be synthesised from charcoal and steam.

A keen adherent of the possibility of transatlantic travel by balloon, Lowe constructed a huge specimen which he named

City of New York, later renaming it to the

Great Western, but though he successfully travelled from Philadelphia to New York, his first attempt to cross the ocean ended in disaster when the balloon was ripped open by the wind, and the repair made to the balloon did not satisfy his sense of safety for a second attempt, so he opted to wait till the spring of the next year. April 1861 saw him fly from Cincinnati, but rather than land at his chosen destination he was blown off-course and landed in South Carolina, where Confederates took him to be a spy and placed him under arrest. Having established that he had nothing to do with the Union Army, he was allowed to go free, but on his return to the North was summoned to Washington by the President, where he would later form and run the Union Army Balloon Corps (see further). The outbreak of the Civil War ended his attempts to fly across the Atlantic.

After the war, Lowe was in great demand for his expertise, but refused all offers to head any more military ballooning operations. He helped all he could though, particularly aiding (but not taking part in) the Brazilian Balloon Corps and speaking to Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, who would of course later be famous for giving his name to one of the all-time classic rock bands. Oh, and also for designing airships, apparently.

Lowe went on to invent many things, including the already-mentioned process for making hydrogen from charcoal, and ice-making machines, and in fact he became extremely rich, but he never returned to ballooning after the war, perhaps dispirited by his reception by the Union Army, or maybe his brush with malaria had taught him to value his life more than he had done.

John Wise (1808-1879?)

Unlike his contemporary above, and other balloonists in America and elsewhere, Wise was purely in it for the sport and enjoyment, and the scientific gain. He was not particularly interested in making money from commercial ventures, and though he joined the Union Air Balloon Corps under Lowe when his country called him, he fell out with the commander and was forever at loggerheads with him. He pioneered the first airmail delivery in 1859, and in 1838 constructed a balloon that would, when ruptured, convert into a parachute, thus allowing the pilot and passengers to descend to the earth safely. He was however badly burned in an accident when the gas in his balloon exploded, and he was also thrown from the basket on another occasion, sustaining injuries that time too, while his balloon ascended without him.

He invented the rip panel, which allowed descending balloons to be gradually deflated, whereas prior to this deflation had to be accomplished by hand, as in a dangerous - and often fatal - manoeuvre the balloonist would have to climb up onto the balloon as it bounced along the ground, to release the valve and let the air out. He is credited with discovering the jetstream, and also the effects of the sun on heating the gas in the balloon, and built a black balloon to take advantage of this fact. He too tried to cross the Atlantic, but, as related in the section on military balloons, coming up, while attempting this with John LaMountain the balloon was caught in a windstorm and badly damaged, putting paid to his ambitions. An ally of LaMountain, he was later reunited with him in the Union Army Balloon Corps, which spelled trouble for Thaddeus Lowe as the two joined forces against him.

In true ballooning and adventurer style, John Wise vanished on a trip from east St. Louis, September 28 1879, and though the body of his passenger was found in Lake Michigan, his own was never recovered, nor was the balloon. This is the last that was ever heard of John Wise.

I was, for some time, a plane spotter. No, you’re right: I never had a girlfriend, and at this point am unlikely ever to. But I’ve always been interested in aircraft, from the days of my childhood when my family would go out for the day to nearby Dublin Airport, and one of my earliest memories is of going out onto the viewing balconies (long closed now) and inhaling the sweet smell of aviation fuel. I tell you, it was my drug. And when I got older I of course then gravitated towards the hobby, this getting even better for me when I started working at the airport.

I was, for some time, a plane spotter. No, you’re right: I never had a girlfriend, and at this point am unlikely ever to. But I’ve always been interested in aircraft, from the days of my childhood when my family would go out for the day to nearby Dublin Airport, and one of my earliest memories is of going out onto the viewing balconies (long closed now) and inhaling the sweet smell of aviation fuel. I tell you, it was my drug. And when I got older I of course then gravitated towards the hobby, this getting even better for me when I started working at the airport.

Linear Mode

Linear Mode