Boeing’s willingness to look to the future and take risks nobody else would led to the company being the first in America - but not the world - to conceive and produce a jet airliner, at a time when everyone else (other than the British, with the ill-fated Comet) were flying on turboprop and piston propellor-driven planes. Boeing’s biggest rival, Douglas, proved to be too timid to make the leap, allowing Boeing to bring their 707 out almost a year before Douglas entered the field with the DC-8. Boeing was, then, quickly established as the first name in aviation innovation, speed and comfort, and the first choice for anyone wishing to travel through the air.

When submitting designs for the US Air Force, all companies tendering - Lockheed, Martin Marietta (both of whom would merge in the 1990s to form Lockheed Martin), Boeing, Douglas and General Dynamics - were instructed that cargo needed to be loaded from the front, so the nose had to tilt up. This meant raising the cockpit above the nose, and would lead in Boeing’s case to the distinctive “hump” that instantly identified their 747.

As the demand for air travel (sorry) skyrocketed after the war, and airports began to crowd up as people waited in line, we return to our friend Juan Trippe, now head of Pan American Airlines. Trippe used his airline’s standing and his own political power and connections to request Boeing to construct a new airliner, to be over twice the size of the current largest, their own 707, putting in a pre-order for twenty-five of the aircraft, which had not even been designed yet, never mind built, and committing an enormous sum, even then, of 525 million dollars, more than a staggering 5 BILLION dollars today.

The man Boeing chose to head the project was this guy.

Although the management team was led by Malcolm Stamper, later to rise to the top job and in fact make history at Boeing as its longest-serving president, it was Joe Sutter who really did the work that counts. An engineer who had worked for the company since 1940, having made a crucial decision to choose between Boeing and Douglas, both of which had recognised the young man’s potential and had offered him a job. Believing that Boeing were more focused on the future - jet development - Sutter chose them, a decision which a former executive of the company believed saved Boeing from being bought out by its rival. Presiding over the initial plans for the Boeing 747 and seeing it through to launch, Sutter is rightly known as the “father of the 747”. Today the main engineering building at Boeing’s Everett plant is named after him.

Looking back to the lost military contract, and with fears that the emergent idea of supersonic travel would eventually make the new airliner obsolete - even today, supersonic passenger travel is not a reality, the only example having been the Concorde, and that was only for the super-rich - Sutter concentrated on making the new aircraft capable of carrying freight, particularly with the inclusion of the idea from the original plans for a front-loading aircraft, something I think (but will have to check) had never been done before. If aircraft were carrying cargo, transport planes like the C-130 Hercules would load from the rear. This idea of a nose-loading design meant Sutter had to also use the raised cockpit idea, which became, as mentioned, the distinctive bump or hump that is the trademark of the aircraft.

Juan Trippe originally wanted a full double-decker aircraft but this was not seen to be possible. In fact, it would be the twenty-first century before the first - and at the time of writing, only - airliner of this type would fly, the Airbus A380. From a quick perusal of the figures, it looks like it has not been the roaring success the company had hoped, with just over 500 sold up to this year. This, despite the fact that it must rank as one of the safest aircraft in the sky, with only three crashes resulting in absolutely no fatalities. That’s damned impressive.

Building the world’s largest airplane was a huge undertaking, and required an equally huge factory. None that existed were suitable, so Boeing had to build their own, on land in Everett, Washington. The area they chose was heavily wooded, and so over six hundred acres of forest had to be felled and cleared. A railway line was also laid, in order to move parts and materials to the factory, though the time chosen to build turned out to be a bad one, as the area saw its heaviest rainfall in years, with the skies opening for sixty-eight straight days. Hey, even Noah only had to contend with forty! In order to meet this challenge, over 100 acres was asphalted, and the building could commence.

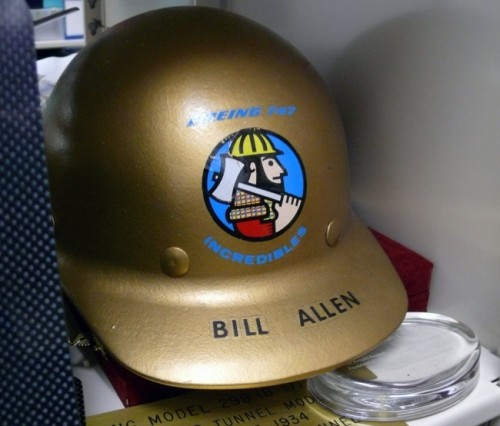

Even so, the rain had delayed and put back their schedule so badly that the aircraft prototype had already been built before the building housing it was completed: they literally built the factory around the aircraft, men having to wear hard hats and contend with with the freezing, driving rain and the cold Washington winds as they worked. Because of the almost insurmountable hazards the team faced in their quest to bring in the aircraft on time, they earned the name “the Incredibles”.

Just to digress very slightly here for a moment, the prevailing ideas about the future of supersonic transport in the 1960s surprise me. Given that Chuck Yeager had only managed to break the sound barrier for the first time in 1949, just over ten years ago at this point, and that the military had only cracked it in 1954 with the F-100 Super Sabre, the chances surely of widespread commercial supersonic aviation were about as likely as, at that point, man colonising the Moon! I mean, even now, here we are in the twenty-first century and still, other than the Concorde, which is now retired, the only supersonic aircraft are still military ones. We still fly on our holidays (well, you do: I haven’t had a holiday in 20 years!) on subsonic airliners. And do we care? Is anyone bothered that it takes hours to fly the Atlantic?

And yet, the idea behind the 747 has repeatedly been stated that it was to be a “stop-gap” aircraft, there just to take up the slack and mark time until the new breed of SST (SuperSonic Transport) airliners came on the scene. I mean, they really believed and expected this. In the mid-sixties! So the 747 was not expected to be the success it ended up being, and it was envisioned by its designers that it would take up the role of a freight-carrying plane when those SSTs were blasting their way across the sky, making New York to Sydney in an hour, or whatever. Jesus in the first-class cabin on a non-supersonic flight! Talk about your predictions of hover cars in the late twentieth century!

Never before - nor, I think, since - has an airline had such a hands-on input into the design of an aircraft. Usually, at least now, airlines decide what aircraft to purchase and order accordingly, but it would not be any exaggeration to say that Juan Trippe loomed large over the design, build and testing of the Boeing 747, doing the equivalent, it seems, of a television network giving notes to a producer or director; he was sceptical about the new aircraft’s proposed speed, also unhappy with its projected range, and while he wanted a double-decker aircraft, the more to fit in as many passengers as possible, this proved outside of safety regulations, as the passengers on the upper deck could not be evacuated, along with those on the lower, in the regulation 90 seconds required by the FAA, the Federal Aviation Administration. And so Sutter and his crew, never happy with the double-decker design anyway, as well as other suggestions such as a high-wing, engine in the tail and and a three-engine model, worked on ways to have the new airliner accommodate the amount of passengers Boeing, or rather Trippe, wanted.

Given that so much was riding on the development of the 747, given Trippe’s buying power and the ability he had to blackball Boeing if they got it wrong, it would not be stretching it at all to say that the very future of the company rested on the success of this new aircraft. With all the money being pumped into it, and no other project being considered, to say nothing of Boeing’s reputation and standing in the world of aviation design, the company would stand or fall on the results. No pressure, then!

Putting all their efforts into the area in which they erroneously believed the 747’s future would eventually lie, as a cargo freighter, Sutter’s team designed a twenty-foot wide body to allow the aircraft to accommodate two pallets of freight side by side. This, then, made the emerging 747 the widest-bodied aircraft in the world at this time. Mind you, if he couldn’t have his double-decker design, Trippe was not a man to allow any of that space to go to waste, i.e., not make money for him. When it was suggested that the raised area behind the cockpit could be used as a rest area for the crew, he shook his head. “Make it into a cocktail lounge,” he advised. Boeing obliged, but drew the line at his idea for passenger staterooms with special windows. Hey, they already had to install a staircase (originally spiral, later straight) in order to allow access to the upper deck and what would be its cocktail lounge, making this, I believe, at least until the advent of the Airbus A380, the only airliner with two floors, the upper reached by stairs.

In terms of safety, though there have been 61 747s destroyed or no longer reparable due to accidents, few of these were down to design flaws or maintenance issues, and indeed half of the losses involved no deaths, which is pretty remarkable, I think. Of course, 747s have been involved in some of the worst and most famous air disasters of our time, but these crashes have only involved the aircraft, not been endemic to it: essentially, they could have occurred with any aircraft, but they just happened to be 747s. Given that there have been over 1,500 747s in service throughout the years, that percentage is very low, about 4%.

Not only did the 747 revolutionise just about every aspect of aviation (and provide more employment, not least due to its additional crew member requirement) but it changed the way airports worked. Juan Trippe would have to spend another 215 million dollars redesigning JFK Airport in order to accommodate the new star of his airline, rebuilding terminals, lengthening runways, and providing new maintenance facilities to accommodate the behemoth, almost another 100 million. Of course, this would be a drop in the ocean compared to the revenue he would receive as Pan Am flew 747s for decades and they did indeed prove to be the seachange (so to speak) that aviation had been waiting for. With the 747 in service, air transport became cheaper for those who could not afford it previously, flight times became shorter and distances covered longer, and those who could afford to travel first class were eager to experience the “flying penthouse” of the upper deck of a Jumbo Jet.

The name, incidentally, was coined by the media. The 747 had never been marketed as a jumbo jet, but the appellation stuck, and helped to make the 747 the best-loved aircraft in the sky for over sixty years.

Of course, any aircraft is only as good as the engine that drives it, and Trippe had originally wanted General Electric’s engine, which had been included in the failed Boeing bid for the military transport contract, this being turbofan, an engine which drew air in and circulated it through huge fans before spitting it out the rear, giving the aircraft its thrust. The GE engine, having been designed for the slower military plane, would not however be suitable for the faster 747, so was discounted in favour of the new Pratt & Whitney JT9D, then the most powerful engine in the world: one of its powerplants had more thrust than all four of those on the Jumbo’s predecessor, the Boeing 707.

At the official signing ceremony for the first contracts for Pan Am’s 25 747s, Trippe made what seems to me an odd announcement: he said the 747 would be “a great weapon for peace, competing with intercontinental missiles for mankind’s destiny”. Uh, what? He compared a commercial airliner to ICBMs? I fail to see the connection. The type of guy he was, I guess he said weird stuff like that all the time.

The timeframe allowed to manufacture, assemble, test and produce the first prototype was staggering; the shortest time an airliner has ever been designed, even today. Three years, from conception in June 1966 to roll-out of the first prototype in 1969. No wonder these guys were called “The Incredibles”! Adding to the pressure on them, Boeing’s two main rivals, struggling to get into the widebody game too, has their own designs in production. Lockheed were working on the L-1011 Tristar, while Douglas had gone for the DC-10, both aircraft ignoring the configuration of the 747’s engines - four slung beneath the wing in pods, as on the 707 and indeed the DC-8) with tail-mounted ones, one either side of the tail section and one in the tail itself, in the case of the DC-10, in a manner Boeing would certainly copy for their smaller 727, but which they assumed was not suitable for a large “jumbo” jet, while the Tristar opted for all three engines being mounted on the tail.

One unfortunate consequence of the overrun on budget as the 747 slowly made its way to reality was necessary cost-cutting exercises at Boeing, resulting in a massive 60,000 redundancies across the company. The project was, in fact, running the risk of bankrupting Boeing. September 30 1968 was designated as roll-out day, and in truth, though Boeing kept this date, the aircraft that rolled out of the hangar at Everett really more staggered out than rolled. Its engines were non-functioning at this point (as Pratt & Whitney were still working on how to provide the needed additional thrust to lift an aircraft whose laden weight had increased by over 1,000 lbs) and no usable landing gear, but the press must not be disappointed and this was all a P.R. exercise anyway, so the roll-out and christening ceremony went ahead as planned, and the Boeing 747 had officially been born.

After all the champagne had been smashed (and more, no doubt, drunk) and hands had been shaken, photographs taken and journalistic reports prepared, the real work began. To all intents and purposes, the aircraft which rolled out onto the tarmac in - for once - bright sunshine on the last day of September was a model: not a mock-up; this was the aircraft all right, but mostly it was an airframe, and much tinkering had to be done before it could fly. The ever-dependable Washington weather provided the worst possible conditions for test flight when the first Boeing 747 to take to the sky lifted off on February 9 1969. The test pilot, Jack Waddel, had been concerned about flying - and more importantly, landing - an aircraft whose flight deck was so high above the nose, and familiarised himself by having a mock-up built which he drove around the field, before he climbed into the cockpit of N7470 and raced her down the runway, pulling back on the stick to tilt the nose up as the first 747 climbed into the grey sky. The first test flight lasted one hour and sixteen minutes, and the aircraft easily fulfilled its promise.

Seems odd to me that the man who basically shepherded the creation and development of the 747 was not there to see it take its maiden flight. Having retired from Pan Am, Juan Trippe had moved to the Bahamas, but William Allen, president of Boeing, had been visiting him when he got the news that the 747 was about to attempt its first flight. He was only seventy at the time, so you couldn’t really say (unless he was sick, which there is no mention of) that he was too old to make the trip, and given the time and indeed money he had sunk into the project, you would imagine he would have wanted to have cadged a lift with Allen back to Everett to see his dream come to life. But no: he did not attend. Maybe, since he was no longer involved with Pan Am, he was not interested any more, or maybe he instinctively knew the 747 would fly without any issues. Still, you’d think he would have wanted to have been there.

Trippe had originally demanded the first of his new 747s be delivered to him by 1969, and this he got - or Pan Am got, as he was by this time retired - in April, Pan Am nodding back to their old Sikorsky flying boats and naming the new 747s as Clipper, a name that would stick with them throughout their service. Other airlines’ orders began to be fulfilled, and soon the Boeing 747 Jumbo Jet was a familiar shape in the sky, at airports, and was the aircraft to have in your fleet. Even today, more than fifty years after it first went into service, it’s still flying, though this year (2022) saw the lowest number of orders of the airliner, with only three, half of the number from the previous year. Some of this, of course, has to be do with a general slow-down and fall-off of aviation due to Covid-19, but the reality sadly now is that the day of the 747, like that of the QE2, has passed, and people are not so much concerned now with luxury as with price. Wide bodied aircraft like the A330 and Boeing’s own 777 and 787 have taken the place of the gargantuan liner, and only this year British Airways scrapped its entire fleet of 747s, the end of an era indeed.

But though its day is passed, and though the chances you will ever travel on one, if you never have, are very low indeed, the legacy of the Boeing 747 will be with us always. The dream, in the end, of a man who had little to do with aviation development but yet created the conditions for the emergence of such a behemoth at a time when others were thinking in completely different and opposing directions, the 747 became the queen of the skies, and proved that bigger was, for a very long time, better.

..cheers Dianne

..cheers Dianne

Linear Mode

Linear Mode