Timeline: 490 BC

The Battle of Marathon

Era

Timeline: 490 BC

The Battle of Marathon

Era: Fifth Century BC

Year: 490 BC

Campaign: First Persian Invasion of Greece

Conflict: Greco-Persian Wars

Country: Greece

Region: Marathon

Combatants: Perisan Empire, City State of Athens

Commander(s): (Athens) Miltiades, Callimachus, Aristides the Just, Xanthippus, Themistocles, Stesilaos, Arimnestos, Cynaegirus, (Persia) Datis, Artaphernes, Hippias

Reason: An attempt to subjugate both Athens and Sparta in retribution for standing against the Persian Empire

Objective: To take Attica, and then Athens and Sparta, and eventually all of Greece

Casualties (approx): 203 (Athens) 4,000 -5,000 (Persia)

Objective Achieved? No

Victor: Athens

Legacy: This battle served to show two things, which had not been apparent before: firstly, that the mighty Persian Empire could be beaten, and secondly, that the Athenians could do so without having to rely on their traditional ally, the Spartans.

Some people just can’t let a grudge go. After the Greek colonies in Asia Minor were conquered by the forces of Darius I, Emperor of Persia, they revolted and were helped in that endeavour by soldiers from Athens, who came to help their Greek brothers. This was in 498 BC. Darius, who had not seemingly even heard of Athens before, demanded to know who these upstarts were who dared attack and burn his city of Sardis, capital of Lydia, one of Persia’s most important cities. When told they were Athenians, he swore revenge on them, and to this end had a slave whisper in his ear three times a day “Master, remember the Athenians.”

And so he did. Let’s take a moment to look at some of the major players here, beginning with the emperor himself. It’s critical to remember that at the time, the Persian Empire was one of the biggest and most powerful empires in the known world, and you simply didn’t stand up to them. If they wanted your country, it was best just to hand it over without any fuss, because if you didn’t, well, they were going to take it from you anyway, and leave a whole lot of children without fathers and wives without husbands, and fill the air with the acrid stench both of burning masonry and flesh.

Darius the Great, c. 550 - 486 BC

Darius the Great, c. 550 - 486 BC

Darius I, also known as The Great, was the third king of the Achaemenid Empire, essentially the First Persian Empire, established in Iran (then known as Persia) around 550 BC by Cyrus the Great. At its height, the Achae - sod it, let’s just call it the Persian Empire, huh? - stretched from the Balkans of Eastern Europe to the Indus Valley in Asia, and was possibly the first major empire, though I’d have to check that. It was the first to devolve rule under its authority to governors or satraps, who each reported to the Persian King. Darius presided over the biggest expansion of the empire, and had among his other titles, King of Kings, King of Babylon and Pharaoh of Egypt. What does seem odd, to me (though it probably wasn’t uncommon at the time) is that Darius did not ascend the throne due to any right of birth, but rather, in a sort of military coup.

He was not born of royal parents (but then, for all I know, neither was Cyrus, whose son, Cambyses II, succeeded him on his death and then promptly went mad) but served in the army and though the king at the time, Cyrus the Great (guess everyone was “the Great” in those days, eh?) had a prophetic dream about Darius taking his throne, this seems to have happened only after Cambyses lost it. Killing, it is said, his own brother, Bardiya, he then died of an infected wound. The murder was, it seems, kept secret and so when an imposter called Gaumata came and proclaimed himself as the brother, Bardiya, the people accepted him - having become restless under the rule of the increasingly-loopy Cambyses - and it was up to Darius, with a cohort of allies, to depose him. It’s pretty likely there was no imposter and that Darius removed the obstacle to his reign by killing Cambyses’s would-be successor, but as they say, history is written by the victors.

You have to admire the selection process for who would become king of these six or seven nobles then. They decided they’d all sit on their horses outside at sunrise, and whoever's horse neighed first would be king. Hey, it beats 270 electoral college votes, doesn’t it? So our friend Darius took the throne, and became the third ruler of the Persian Empire. However taking the throne and holding it are two different things, and Darius found that the official story from the palace of how he took power was not always believed, leading to revolts in Assyria, Babylonia and Egypt, all of which he ruthlessly put down, claiming he had killed “nine lying kings” in the process. Rebellion was closer to home, too, though, much closer. One of the nobles who had helped him to the throne, Intaphernes (is this where the word interfere comes from?) paid Darius a terrible insult which led the ruler to believe his ex-comrade was planning to seize power for himself, so, as you do, he slaughtered him and almost all his family.

Darius conquered all before him, but it was his attempts - eventually successful - to put down the Ionian Revolt in the Greek-inhabited areas of Asia Minor and the surrounding islands which drew support from Athens and Eretria, actions which would cause him to turn his eyes towards Greece itself, and especially Athens, and which would lead to the first major defeat for his army under his rule.

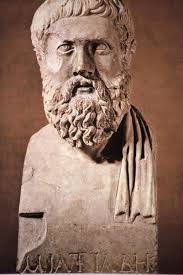

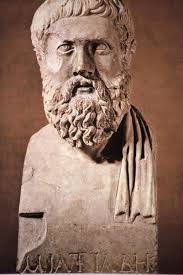

Miltiades the Younger (c. 550 - 489 BC)

Miltiades the Younger (c. 550 - 489 BC)

Odd as it may seem, though there was a Miltiades the Elder, he was not his father, the Elder dying without issue, and passing his kingdom on his death on to his nephew, Stesagoras. Miltiades the Elder had set himself up as tyrant of the Thrace Chersonese (which is now the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey) which he ruled for 35 years until his death in 520 BC. Note: although today the word tyrant is used as a pejorative for a despot or dictator, in ancient times it had a different meaning, simply indicating that the holder of the title was the unchallenged ruler, who had taken power by his own hands and had not been elected. There were a lot of tyrants in ancient Greece, as we will see. Anyway, poor old Stesagoras didn’t last long, dying in 516, a mere four years after taking power, felled by “an axe to the head”. That’ll do it all right. Mind you, it doesn’t say who wielded the axe.

Back in Athens, Miltiades the Younger, Stesagoras’s brother, was doing well and had become the archon, or chief magistrate, of the city, under the rule of the tyrant (see? I told you) Hippias. When someone perhaps misunderstood the term “let’s bury the hatchet” with regard to Stesagoras, Miltiades the Younger (who, given his uncle is now dead we will just in future refer to as Miltiades) was sent to take over. He immediately established his power and tricked the nobles into being captured, then consolidated his hold over the city. Around 513, our friend Darius made his appearance and subjugated the Thrace Chersonese, making Miltiades a vassal and forcing him to fight for him. However when word came to the Persian king that his Athenian vassal had been plotting to destroy a bridge he and his men had been left to guard, to prevent Darius’s crossing the Danube into Scythia, he was less than pleased and Militades had to flee. He joined the Ionian Revolt, and when that was crushed, legged it back to Athens, possibly to await the vengeance of his ex-master, which was surely to come.

He wasn’t exactly welcomed back with open arms though. Hippias had been deposed and exiled, tyranny abolished in Athens and democracy had taken its place. As a tyrant himself, the Athenians were sceptical of Miltiades, but his knowledge of Persian tactics and experience fighting them would be invaluable, and so he was forgiven and allowed to rejoin the city, which he would defend in the battle to come.

Hippias (c. 547 - 490 BC)

We’ve heard of this guy already. In a tactic which would be repeated by deposed rulers or out-of-favour nobles or generals down through history, Hippias would lead the Persians back to his old stomping ground of Athens, in the hope of being able to claim it back and being re-established as the tyrant there once Darius and his boys had kicked the crap out of the fledgling democracy and reinstalled tyranny. Not saying they all didn’t anyway, but Hippias seems to have lived up to the more modern interpretation of the word tyrant, being a cruel ruler who executed his subjects on a whim, and levelled crippling taxes on the ones he spared. Eventually the people had had enough and Hippias was deposed and exiled. Given that he had looked to the Persian empire for assistance against his growing enemies when in power, it was only natural that he should seek shelter among them, always hoping one day to return and retake power. Unbeknownst to him, he had allies in the Spartans, who didn’t much like this idea of democracy and thought Athens was becoming a threat under it. Get the tyranny back, they thought, and scotch this whole stupid idea before it had a chance to breathe. But despite threats from Persia, at the urging of the Spartans, that they would attack if Athens didn’t take Hippias back, they were told to bog off. Understandably, they did not take this well.

When the Ionian Revolt kicked off (yes, this again!) Hippias was delighted when Athens aided the rebels as, once they were defeated, he was able to float the idea of an invasion of Greece to Darius, who nodded sagely, remembering the words his slave was commanded to whisper in his ear. “Let’s go get them bastards!” he may have said, though there are no records of his actual words. Hippias suggested Marathon as a good place to land, and Darius agreed.

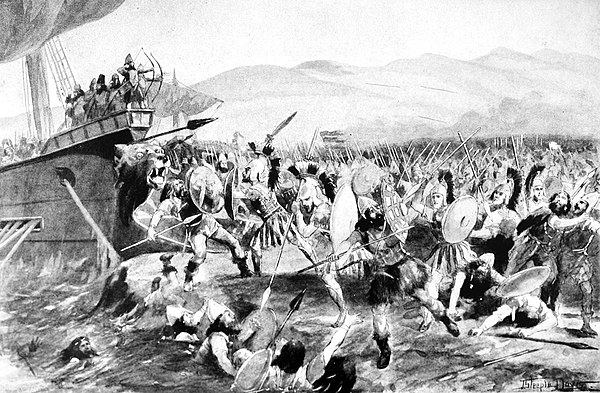

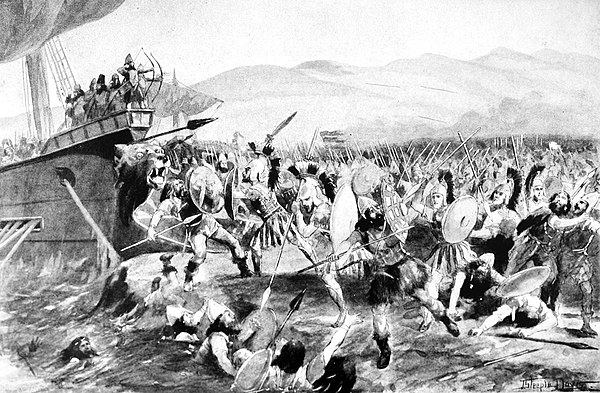

The Battle

So Darius’s fleet arrived in the Bay of Marathon, 25 miles from Athens. Before they could move inland though, Miltiades, familiar with the Persians’ tactics, marched his army there and blocked off the only two exits from the plain. Seeing they were hopeless outnumbered (around 125,000 to 10,000, very roughly, though not every man fought in the battle or was used) he sent a runner to Sparta, hoping they would come to their aid as a fellow Greek city state. Unfortunately the Spartans were in the middle of a holy festival which could not be disturbed (so they said) and would not be able to send reinforcements for ten days. This could have been a ploy of course; as mentioned, the Spartans had no love for the Athenians (though I haven’t read here any actual accounts of them fighting each other) and had in fact tried to force them to take back their deposed tyrant, on pain of being attacked by the very forces who were now threatening them. Then again, they might have been looking at the longer game. If Darius did succeed in taking Athens he was unlikely to stop there, and the Spartans would find themselves fighting not only his forces, but those of Athens, now newly under the control of the triumphantly returned Hippias.

Anyway, whatever the truth, Sparta were no help, but the small town of Plataea did send 1000 men, which is not to be sneezed at when you’re up against an army over ten times your size) and for five days the armies faced each other across the plain of Marathon in stalemate, the Athenians waiting for the Spartans to arrive, the Persians unable to break out without great losses. Look, democracy is all well and good, but can we really trust a system of command that had ten generals directing the battle, and who rotated the command between them every day? So one day General X was in charge, the next General Y and then General Z, and so on, until it came time for General X to have his shot again? Sounds like a recipe for disaster. But that’s apparently how they did it, and Miltiades was one of those ten generals. In overall command was the polearch, Callimachus, to whom all ten deferred.

Or did they? Because according to accounts, even on days when he wasn’t in command Callimachus ordered the generals to report to Miltiades. Sounds like a man who perhaps was looking for a fall guy. At any rate, the battle seems to have been a case of the old “game of two halves”, with the first half being the two armies eyeing each other across the plain for - well, some accounts say five, others say eight days, but days certainly - and the second half seems to have, if you’ll forgive extending the football analogy a little, kicked off with a sudden rush from the Athenians down a slope, which took the Persians by surprise.

But there was a hell of a lot riding on this. In terms of the Persians, of course, the prize was the whole of Greece and the destruction of the Athenian (and, presumably, the Spartan) states, removing any further interference from them to the now-subjugated Greeks in Asia Minor, further tightening Darius’s grip on and extending his empire. Failure here would mean a humiliating defeat for the Persian king - the first of his rule - and reputations are both built and lost on decisive battles. For the Athenians it was all in: they had to take all their soldiers to Marathon, but this left Athens undefended should they lose and the Persian fleet make the relatively short trip up the river to the city state. It would mean the reinstallation of the tyranny under the traitor Hippias, the abolition of the almost embryonic democracy, and, though they couldn’t have known it at the time of course, this would have had catastrophic repercussions for the rest of the western world, as we owe so much to Greek art, literature, politics and science. It could have been the beginning of a dark age worse than that in Europe during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, and would surely (I assume) have seen Islam as the ruling religion in most of the world, fundamentally changing the balance of power.

Linear Mode

Linear Mode