Timeline: 2016

Timeline: 2016

The Siege of Fallujah (February - June 2016)

Era: Twenty-first century

Year: 2016

Campaign: Anbar Campaign

Conflict: Iraq War/War on Terror

Country: Iraq

Region: Fallujah, Anbar Province

Combatants: ISIS, Iraqi Security and Armed Forces (with air support from Coalition Forces - USA, UK, Australia) and also Iran

Commander(s): (Iraqi/Iranian) Haidel al-Abadi, Suhaib al-Rawi, Issa Sayyar al-Isawi , Major Sayeer al-EsIsawie, Qaem Soleimani (ISIS) Abu Waheeb, Hussein Alawi, Ayad Marzouk al-Anbari

Reason: To retake the city after its fall two years previously

Objective: Regain control of the city and thus the province, push ISIS back

Casualties (approx): Very roughly about 5,000 on both sides

Objective Achieved? Yes

Victor: Iraqi army and its allies

Legacy: A major defeat for ISIS and secured the safety of Baghdad. Many top-level leaders killed; a demonstration that the Iraqi army could defend its own country without (too much) intervention by or help from the USA or other outside allies. Created a humanitarian disaster and left thousands of people homeless and destitute, and set the template for later conflicts.

Like most battles in the Iraqi War, this one was heavily connected to others and was in fact also known as the Third Battle of Fallujah. In Iraq, control of this territory or that territory was contested almost on a monthly basis, with one side gaining the upper hand only to lose it soon after, and the whole thing taking on the aspect of a deadly game of tag. One day, the local Iraqi forces were “it”, the next, they were chasing ISIS. One is reminded, grimly, of a nevertheless funny scene in

Star Wars (or if you prefer,

A New Hope, though it will always be the former to me, the original) where Harrison Ford, seized by a sudden sense of either courage or madness, charges a squad of stormtroopers on the Death Star and they run off, with him in hot pursuit. Off-camera, someone eventually realises this is just one man, and they turn and begin chasing him, back the way he came.

So it would seem was the case with Iraq, where ground won, rather like the trench warfare stage of the First World War, was rarely held, and everything was in a perpetual state of flux, including the government. Fallujah was an important and strategic town, and I’m about to tell you why, but in order to do so, I need to take you back two years, to the original Battle for Fallujah, which did not go the west’s way.

To understand why this city became such a focal point for resistance (even if, in the end, the actual citizens became nothing more than a cross between cannon fodder and prisoners) we need to look back to almost the very beginnings of the Iraq war, the 2003 invasion. Fallujah had been a stronghold and powerbase of the powerful Ba’ath Party, which was, yes, the party of soon-to-be-deposed-and-later-hanged President Saddam Hussein. It was primarily a Sunni city, this being the ethnic group Hussein belonged to, the other being the Shi’ites, and each hated the other with the kind of revulsion and anger you might have seen on the streets of Belfast on the Twelfth, when the Unionist Orangemen marched through the Republican areas where lived those loyal to the IRA.

As usual, the coalition forces almost literally shot themselves in the foot from the start, “accidentally” bombing a market and killing hundreds of civilians. Quite how, with the supposed “infallible” computer-aided guidance systems we’re supposed to have now, a bomb can go so spectacularly off target is something I find hard to understand, but you kill civilians at your peril, and so the resistance against George W. Bush’s coalition forces hardened, and it never really thawed, as Fallujah became a rallying call for then-Al Qaeda fighters, and for those who had lost everything when their leader had been deposed. Before March 2003, the most profitable and cushiest jobs went to members of the Ba’ath Party only, so with the ousting of Saddam Hussein also went their meal ticket, and things changed radically as their city, and their country, was taken over by foreign invaders.

And let’s not make any mistake about it: this was an invasion. Not a response to a cry for help, not a strategic and necessary moving in of assets, not a pre-emptive strike to forestall an attack. Iraq, while certainly ruled by a despot, was no threat at all to the USA, to the west or to the world outside of the Middle East. Hussein’s posturing had proven to be just that, empty braggadocio spouted by a windbag who, when someone actually stood up to him, when he met a bully as big and powerful as he was, went scurrying home and hid under his bed. The First Gulf War, barely deserving of the name, was over in a matter of a month, and over decisively. Hussein knew he could never take on the mighty powers of the west - especially USA and Britain - on his own, and he had few allies that were willing to step up and help him, and thus alienate not only the Americans but also the rich and powerful Saudis, who were nominally allies of the US (despite almost all of the 9/11 attackers being from there, but that’s another story).

So there was zero chance of Iraq launching any sort of offensive at the west, and the best it could do would be to throw shapes at Iran - as it did, and was again beaten - and fume to itself, impotent and unimportant. The idea of Saddam Hussein possessing WMDs - weapons of mass destruction, such as biological and chemical weapons or even nuclear bombs - was as ludicrous as the idea Donald Trump actually won the 2020 Presidential election. It just could never happen. But fear is a great motivator, and most of the time you just have to say the right words to make people s

hit themselves and demand action (let’s not forget Hitler’s dire warnings about the “international Jew”, shall we?), action you’ve just been waiting to be asked to take.

So there was no basis - no true basis - on which the USA and its allies invaded Iraq, on the face of it and being entirely fair, a peaceful country which threatened nobody and had as much to do with 9/11 as I did. But they did it anyway. The USA has been used to “intervening” in any conflict in which they believe they should get involved, whether on grounds which are ideological, religious, financial or territorial. In the case of Iraq, it was money, pure and simple. Iraq had oil, America wanted it, and what America, the biggest bully in the world’s playground, wants, it takes.

This time, however, it was about to bite off a whole lot more than it could chew.

The American combat mission in Iraq has ended. Operation Iraqi Freedom is over, and the Iraqi people now have lead responsibility for the security of their country.” President Barack Obama, The White House, August 31 2010

The Fall of Fallujah, December 30 2013 - January 4 2014

After seven years in Iraq following its invasion by the US-led coalition forces in ostensible response to the terror attacks of September 11 2001 which brought down the twin towers of the World Trade Centre, a new president was in office and Barack Obama had been elected partially on a promise of bringing the troops home, and ending an occupation America was getting increasingly dissatisfied with, seeing another Vietnam unfolding before their eyes. As the words of former President George W. Bush at the outset of the invasion, that there would be no US casualties, rang hollow in the wake of over 4,000 coffins arriving in American airports during the period up to 2008, the new president realised the US was never going to win this war, and it was time to exit as gracefully as possible. To that end, he began preparations to reduce, and finally remove all US troops from Iraq, and by 2010 the last brigade had departed.

While this decision is easy to criticise, especially with the benefit of hindsight, and while its historical repetition is being played out in Afghanistan as I write this, a permanent presence in Iraq was never going to be of benefit to the US government, and at some point the question had to be faced: what were all these young men and women dying for? Given that the Iraq War had been predicated on a bald-faced lie, or two actually - that Saddam Hussein was somehow tenuously and nebulously responsible for 9/11, and that he was amassing weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) for use against his enemies - there really was no reason for America to be there at all. They weren’t guarding or protecting any US interests (unless you count peace in the Middle East, which had totally failed as an endeavour, and was always doomed to), there weren’t any American citizens in Iraq who needed their protection (other than those in the US embassy, who could easily be evacuated) and nobody really wanted them there. Over seven years they had destroyed the country, plundered it of its riches, forced it to pay big American corporations such as Haliburton to rebuild what its countrymen had destroyed, and made the situation there much worse than it had been before the first bombs had fallen.

However, without an effective US presence there, insurgents became emboldened and moved in. The Islamic State - variously also known as ISIL, Daesh or ISIS - gathered followers and pointed to the weakness of their opponents, citing American withdrawal from Iraq as their victory over the crusaders (just what Randy Crawford had to do with it I don’t know) and pushed to take advantage of the power vacuum. The government set up by the US, essentially the normal puppet power installed by the invader, was weak and shaky, and with their protectors gone back home were easy prey, though this did not mean they would not fight hard to retain what they had already struggled for, and what had been built, with the help of Uncle Sam. Nevertheless, they were fighting a lost cause when the forces of ISIS hammered into the city of Fallujah in Anbar Province (it’s a trap! Oh no wait; that’s Admiral

Ackbar, isn’t it?) and took it in a few days.

This was a great victory for ISIS, and Al-Qaeda, the capture of their first city in Iraq, and a base from which they could launch an attack against the capital, Baghdad, only forty kilometres away. It was clear this could not be allowed to happen, and so an offensive was launched to recapture the city. It began with the taking of Al-Karmah, 15 kilometres from Fallujah, in May 2015, which gave them something of a base from which to plan and prepare their attack on Fallujah. However later that month ISIS forces took Ramadi, another town in the Al Anbar province, which was not recaptured by Iraqi forces until the following February. Having captured several villages around Fallujah in the same month, the stage was now set for the siege of the ISIS-occupied city.

“There is a volcano of resentment boiling inside Fallujah.” Iraqi military, February 19 2016

“If those groups inside aren’t supported, Daesh will have huge revenge. There will be the biggest bloodshed ever.” - Issa al-Issawi, Fallujah Mayor-in-exile, February 19 2016

Siege of Fallujah

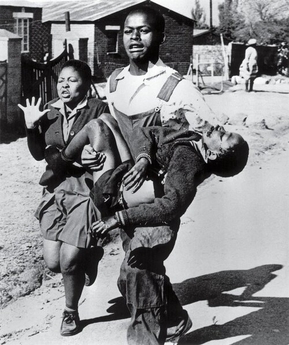

If there’s one thing you can be guaranteed in any siege - at least, one of any appreciable length - it’s that civilians will suffer. As the Iraqi forces took all of the neighbouring Khalidiya Island and effectively cut off the city of Fallujah, the supply lines feeding the city were completely severed, and it was estimated that from 30,000 to 60,000 people would starve, but the siege went ahead as planned. Inside the city, unrest bubbled. This was no siege by an army protecting its citizens, supported by them and concerned for their welfare. There was no attempt at negotiating the release of any of the civilians, not even the women or children, and as what food there was was reportedly hoarded by the ISIS militia, leaving the ordinary folk to starve, and with repressive action being taken against the citizens, an uprising was being born.

Reports emanated from the city (impossible to corroborate, as ISIS had, as per standard procedure, cut off all communications with the media and the outside world, destroyed mobile telephone networks and cut off internet access), of elderly men being “humiliated” when they asked for food, women being beaten, and Sunni tribesmen inside the city finally had enough and attacked the headquarters of the hisbah, the ISIS moral police, for want of another word, they who rigidly enforced Sharia law on the streets. The building was burned and everyone inside killed. The uprising quickly spread, but it was obvious that the tribesmen would need assistance from outside the city if they were to retake it and put ISIS to flight. The revolt however did not succeed and was crushed ruthlessly (why ruthless I often wonder? Does anyone ever do something

with ruth? What

is ruth anyway? Sorry) and took 180 prisoners, but just then the Iraqi military began shelling the city, and moved troops towards the city in preparation for its storming. The siege was about to become a battle.

Linear Mode

Linear Mode