Back to King Edward and those pesky Scots though. While he had scored a major victory in defeating and breaking the armies of both Moray and Wallace, and having the latter pay the ultimate price for what he saw as treason, Edward’s campaign in Scotland did not go to plan, and in the end the Pope commanded him to withdraw, and he did. For now. But he was back in 1301, this time with his son. Again, he failed to conquer the country and sodded off back to England, declaring a nine-month truce as the following year began.

Robert (the) Bruce (1274 - 1329)

Robert (the) Bruce (1274 - 1329)

The next Scottish patriot to rise against the king was arguably the most well-known, other than perhaps Rob Roy, and in no small part as he also features in the movie Braveheart. After Wallace resigned the Guardianship of Scotland following his defeat at Falkirk, Bruce held it jointly with John Comyn, though the two men did not see eye to eye. Descended in an unbroken line from the Scottish King David I, Bruce had been (as already related) one of the claimants for the crown on the death of the Maid of Norway, which led to Scotland’s Great Cause, but though his claim had been one of the strongest he was passed over in favour of John Bailiol. He then initially fought on the side of King Edward, holding Carlisle Castle when John Comyn and his men attacked it just prior to Edward’s first invasion of Scotland. When Scotland rose up in the face of the harsh treatment and lack of respect the king paid them, Bruce switched sides and rode against Edward.

At Irvine he had his men drawn up for battle against Henry de Percy, grandson of the Warden of Scotland appointed by Edward, but dissension and in-fighting among the Scots led to their capitulation, and while William Wallace was busy raiding Scone, his supposed ally Bruce was swearing fealty once again to Edward. But while Bruce was at the English court word came to the king that John Bailiol had made a deal with him to abdicate the throne of Scotland in Bruce’s favour, and he ordered Bruce be arrested. Bruce, however, forewarned, hauled ass back to Scotland, where he prepared for war against his old master.

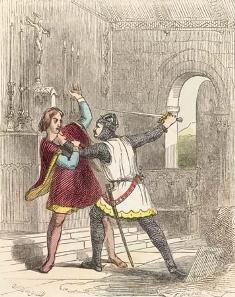

When Bruce found out that Comyn had reneged on the deal, that it was in fact he who had spilled the beans to Edward, he confronted him in the Abbey of Greyfriars and stabbed him. Some accounts say his supporters finished the king off, others that knights loyal to Bruce returned to the chapel, Comyn only having been wounded, and “made sure”. Either way, the king was dead, long live the king, and Bruce claimed the throne he believed he should have had in the first place. For breaking the sanctity of the church and spilling blood in the holy place, Bruce was excommunicated.

King Robert Bruce - Heavy Hangs the Head

The new king’s reign did not start off on the best footing. He had to be crowned twice, as the wife of John Comyn (not the one Bruce murdered, another one - between that many Andrews and Roberts and Johns, you’d wonder how any Scot ever knew who was being addressed!) claimed the right to crown Robert for her young brother, the Earl of Fife, who was a prisoner of the English. Yeah I know: I don’t get it either. But even though he ended up having two coronations, Robert couldn’t have missed the very glaring fact that he would have been the first Scottish king not to be able to sit on the Stone of Scone as the crown was placed on his head, Edward having half-inched it and trotted off merrily back to England where it was kept under, presumably, lock and key.

Chivalry is dead - and so are you: The Battle of Methven

Chivalry is dead - and so are you: The Battle of Methven

He lost his first battle against the English king, at the Battle of Methven when he faced the new Lord Lieutenant of Scotland, the Earl of Pembroke, Aymer de Valance. His boss, fed up with the annoying Scots resisting his power, gave the earl orders to spare nobody, take no prisoners, show no mercy. Unaware of this order, I guess, Robert the Bruce offered to meet de Valance in single combat, but the earl shouted back “can’t manage it today, old bean. Bit too late for me. Let me check my diary: oh yes, indeed, splendid. I can fit you in the morning, how’s that?” I suppose the exact dialogue went somewhat differently, but you get the picture. “Fair doos,” responded the new Scottish king, agreeing. “I’ll see ye in the morn then ye sassenach!”

Little did he know though that de Valance cared little about his chivalric behaviour, and when the Bruce and his men bedded down for the night, they had a nasty visit from the English, who fell upon them in their jammies, possibly, and soon put the Bruce and any of his men who could manage to get away to flight, the rest I suppose killed, as per the orders from the king. Worse was to follow for the harried king though, as his hated enemy - or at least, an ally of same - was waiting for him as he made his escape. What took place could very well have ended the reign of Robert the Bruce, and nearly did.

The Battle of Dalrigh: Caught between a loch and a hard place

The Battle of Dalrigh: Caught between a loch and a hard place

Alexander MacDougall, head of the MacDougall clan and descended from Somerled, the First King of the Isles and Lord of the Hebrides, was related by marriage to John Bailiol, the deposed king of Scotland chosen by Edward I, and his cousin, John Comyn. Having naturally taken the side of Bailiol and Comyn, the MacDougalls lost everything when the former was killed by Robert the Bruce and he, Bruce, was crowned king. MacDougall, therefore, was only waiting for his chance to avenge himself on the man he saw as the usurper, and that chance came directly after the Battle of Methven, as the remnants of Bruce’s army - said to number no more than 500, including women and older people who were hardly in a condition to fight - ran into an ambush led by his son John (oh yes god damn it, another one!) which he had laid with his over 1000 men.

Battle was joined but very one-sided, the king reported at one point to be personally fighting alone almost literally between a rock and a hard place - stuck in a narrow passage between a loch (lake) and a hill, and there was a very good chance he could have fallen, which would have changed Scottish history considerably. Against a superior force, unprepared and unable to use his trick of making the terrain work for him, as MacDougall knew it as well as he did, he was quickly routed. He did survive, but as a fighting force his army was over and done with.

Some short time later members of Bruce’s family were captured, and other than the women, all killed. Some respite was on the horizon for the outlaw Scottish king though, as in July of 1307 Edward finally died, though his campaign was carried on by his son, Prince Edward, now Edward II. Another link with Ireland suggests the possibility that Bruce went into hiding here, as he waited for a chance to strike back at the king, though there are other places it’s agreed he could also have taken shelter.

In spring Bruce returned to Scotland, now mostly under English control or held by nobles hostile to him, and scored a minor victory when, at the Battle of Glen Trool, he had his men loosen boulders at the top of a hill and, Wiley Coyote-like, rain them down on the approaching English soldiers, killing most of them. It was his old adversary, Aymer de Valence, who led them, and he was to meet him again in battle when they clashed at Loudon Hill. Unlike his contemporary Wallace, and like Andrew Moray, Bruce had learned an important lesson waging his guerilla war against the English, and that was that he who knew and could use the terrain to his best advantage was more likely to win, even if the numbers were against him. De Valence had not known about the loose boulders at the top of Glen Trool, and this had been his undoing. His lack of knowledge about Loudon Hill, and the digging by Bruce of three large trenches to focus the earl into approaching his enemy in single file was another way of turning his familiarity with the land to his advantage, and again he won the day, though de Valence escaped.

It’s a Scottish thing - ye wouldnae unnerstan’ - The Defeat of John Comyn (another one)

It’s a Scottish thing - ye wouldnae unnerstan’ - The Defeat of John Comyn (another one)

When Edward II had to return across the border to deal with domestic issues at home, Bruce rampaged through Scotland, scoring some victories, but his main aim was to end the feud between his family and that of the Comyns. He had no intention though of burying the hatchet, anywhere other than in Comyn’s head, that is. You’ll remember that Bruce killed another John Comyn in the Greyfriars Chapel, an action for which he was excommunicated. Since then, not surprisingly, the Comyns and the Bruces, and the allies of each, had been at war within the Scottish kingdom, and finally one of the cousins of the slain ex-king and the now-fugitive king met at Inverurie to settle the matter once and for all.

The Battle of Inverurie

A strange one, this. It seems that all that harrying, dodging, sneaking, attacking and retreating had taken its toll on poor King Robert the Bruce, and he got very sick. It doesn’t say what he suffered from, but maybe nervous exhaustion? Who knows? But the point is that at the time of this battle he was being ferried around by his men on a kind of litter, unable to walk or ride a horse. The news of this had spread, and had given Comyn’s men heart, so when the king struggled out of bed and onto a horse in order to face his old enemy, it seems Comyn’s army just, well, got scared and all ran off. Seems odd I know, but that’s what the account says. Comyn escaped but had to flee to England, where he died later that year, removing the power of the Comyns from Scotland and providing Robert the Bruce with a powerful and telling victory.

Scotland’s Shame: The Harrying of Buchan

Scotland’s Shame: The Harrying of Buchan

In the wake of Comyn’s defeat he flew to his stronghold, Fyvie Castle, but it was well defended and Bruce did not intend to waste time and men laying siege to it. However there is nothing quite so dangerous as a vengeful king, other than a woman who has been told that her bum does indeed look big in that, and so Bruce took his anger at Comyn out on his people, burning villages, killing cattle and livestock, slaughtering men, women and children and basically giving the people of Buchan a taste of what Oliver Cromwell would dish out in Drogheda three hundred years later.

Technically, of course, he didn’t do it: he was too sick, despite his show of bravery at the battle, but he ordered his brother Edward (again, not too much in the way of originality about the choosing of names here -at one point, Edward could have been said to have been fighting against the combined forces of Edward and Edward!) to carry out his wishes, and so he did. For months the countryside was laid waste to, people harassed and harried, presumably a lot of the old rape and pillage taking place, and castles were “reduced”, whatever that means. Reduced to rubble? Reduced in size? Reduced to having to swear fealty to Robert? Reduced in power? Who knows? One thing is certain though: it was not good for those who held those castles.

The flight of Comyn and the resultant destruction of his lands by the raging king’s brother served to rob Bruce’s ex-rival of any loyalty he had in the area. It took thirty years before John Comyn’s successor, Henry Beaumont, stuck his nose into the area and he withdrew it again pretty quickly when he was attacked, legging it to England where he popped his clogs, no doubt lamenting the loss of Buchan to the Bruces, in 1340. His own son, John (yeah, yet another one!) had the good sense to back away, hands raised and say “Nah, nah, you’re all right there mate. Don’t want it thanks all the same” when offered the earldom. Nobody of the Comyn line wanted Buchan, and Buchan did not want them. A century of Comyn rule was over.

Bruce now turned his vengeance on the MacDougalls, allies of his hated enemy.

Hell’s coming five paces behind me: The Battle of the Pass of Brander

Having destroyed the power of the Comyns in Scotland forever, Bruce started mopping up their supporters, and first on his list was the MacDougall clan. He had not forgotten what he must surely have seen as the shameful attack on a tiny force composed of old men and women, at the Battle of Dalrigh - and more importantly, perhaps, his own ignominious flight from there into hiding, and he meant to pay them back in spades, or whatever phrase Scots use instead of spades. This time he was an unstoppable force, not only marching with legions of soldiers but also commanding galleys which sailed up Loch Linne, and though his old adversary was too sick to fight at this time, Alexander MacDougall’s son, John, who had dealt Robert such a crippling blow at Dalrigh, stood ready to take him on.

They were hopelessly outnumbered though, and demoralised by the size of the force facing them, and when Sir James Douglas (known as Black Douglas), one of Bruce’s chief commanders and most loyal supporters led a force of archers high up onto Ben Cruachan, the highest mountain in Argyll, the MacDougalls’ cause was doomed. John escaped in a galley while Alexander had no alternative but to swear loyalty to Bruce, though he later fled to England, where he died in 1310.

With the defeat of the MacDougalls Bruce’s power in Scotland was uncontested, all his enemies slain, fled or forced to pledge their fealty to him. In a quite amazing feat of military prowess, Robert the Bruce had, in two short years, gone from being a fugitive outlaw king in name only to making himself the undisputed ruler of Scotland, the most powerful man in the country.

But England awaited…

Linear Mode

Linear Mode