Chapter IV: The Book of Invasions, Part three:

Boots on the ground – the beginning of eight hundred years of occupation and oppression

Timeline: 1073 – 1316

With the death of Brian Boru Ireland descended - or rather, returned - into petty wars, as claimants to the throne of Ireland (not literally: there was no single throne, no ruling palace or even indeed any idea of real kingship in Ireland, and would not be for hundreds more years, but various chieftains and warlords vied for the position of High King of Ireland) fought among themselves, but nobody was a worthy successor to Brian. As ever, the power of the Christian, and in particular Catholic Church, would be the real force for change in Ireland, and the real power would rest not in Dublin or Ulster, but in Rome. With increasing dissatisfaction with what it saw as the unacceptably semi-autonomous power of the Church in Ireland, and the reported misuses of power there, the papacy was eager to assert its own control over the island. Pope Gregory VII had already established his absolute accepted rule,not only over the Christian Church, but all of creation (and that surely included Ireland!) so the way was clear, in 1155, for Pope Adrian IV (who just happened to be an Englishman, the only English pope in history) to issue a papal bull.

A papal bull, in case you don't know, was not some sort of pet the pope kept, nor was it a description of doubletalk coming out of the Vatican. It was a letter signed by the Pope, each a formal decree, a command that something must be done. Papal bulls could start or finance wars, revoke kingships or even excommunicate sinners from the Church, denying them the benison of Heaven on their death and banning them from churches. They could also provide annulments of marriages and, as in this case, confer authority upon a person to do something the pope wanted done. The papal bull of 1155, called

Laudabiliter (“laudably”, or “in a praiseworthy manner”) allowed King Henry II of England to invade, at his convenience, Ireland, in order to bring it into line with religious orthodoxy. In other words, the King of England was encouraged to reassert the power of the Pope over the Irish monasteries.

Henry, however, was a little busy, fighting those pesky French, his eternal enemy, so he deferred invasion until such time as it might be possible, or, in the event of the war ending in victory for him, politically expedient. With rather telling Irish tragedy though, it would actually end up being the Irish – or one Irish lord, anyway – who would force Henry's hand and bring his troops to the shores of Ireland, where, once entrenched, we would suffer their yoke and oppression for the next nine centuries. As you read on through this journal, you may get an idea of exactly why Irish people hate English – historically; not so much now, but even when Ireland plays England at football or rugby, the latter is always referred to as “the old enemy”.

Prelude to invasion: the Normans

The story is well known in Ireland about Diarmuid MacMurchada who, having abducted the wife of a rival chieftain, had his lands in Leinster confiscated by the closest to a High King Ireland had at the time, the powerful Rory O'Connor. Forced to flee abroad, Diarmuid plotted revenge and swore to regain his kingdom. If you feel bad for him, don't: legend has it that the man said himself he would rather be feared than loved, and any of his enemies he did not have killed outright he had castrated and blinded, so that they could have no progeny who could avenge them. Indeed, the story is told of the time he became incensed because leadership of the Abbey of Kildare had been granted to one of his rivals, and furious he rode there, attacked the place and seized the abbess and had her thrown into a soldier's bed and raped, thereby disqualifying her from holding her position. Not a nice guy!

And forevermore branded as a traitor in Ireland, though some historians see it differently. However the indisputable facts of the case are this: Diarmuid fled to France, where he found the English King, Henry II, engaged in war. Busy as he was, Henry could not spare any troops to help the dispossessed king, but he allowed him to go to Britain and recruit men in his royal name, in return for Diarmuid's promise to submit to him, hold the province of Leinster in his name and offer his daughter to the leader of the troops he would raise.

And he found troops in Wales, men who called themselves Normans. These were the descendants of Vikings who had come to originally raid and then settled in France, in what is now known as (anybody?) Normandy. Gradually acclimatising to and being assimilated by the French lifestyle, they basically became French, and when they invaded England in 1066 led by the famous William the Conqueror, a whole new way of life was stamped on the English nation, and would be visited on the Irish too, a hundred years later. 1167 saw the first wave of Norman troops arrive in Ireland, where they quickly regained Diarmuid's kingdom, and two years later their leader brought more troops, this time taking Dublin and Waterford, sweeping all before them contemptuously.

Strongbow (1130 – 1176)

Having inherited his late father's lands as the Earl of Pembroke in 1149, Richard Fitzgilbert de Clare, known as Strongbow, lost them again when he supported King Stephen when Henry's mother, the Empress Matilda, rode against him but failed to take the throne of England. When Stephen died, and Henry inherited the throne after his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry had his revenge on the rebel earl. Seeking to better his fortunes, Strongbow was receptive when Diarmuid came looking for help to reclaim Leinster by force of arms, and after first dispatching some of his knights to aid the dispossessed Irishman, Strongbow himself followed Diarmuid to Ireland where he began a two-year rule of the country.

1170 saw the arrival of Strongbow and he laid siege with his knights to Dublin and Waterford, taking both towns easily. The Irish had never seen anything like the Normans: they were mounted and armoured, and they used longbows and crossbows, which could kill with great accuracy at a distance, and pierce armour (though the Irish wore none; indeed, they often charged naked into battle), as well as long lances. There was no contest, and Rory O'Connor, the

de facto High King of Ireland, was reduced to the role of a provincial king. Diarmuid MacMurchada, who had married his daughter Aoife to Strongbow as part of the agreement, and had hoped not only to regain Leinster but to take all of Ireland and make himself High King, would not live to see this ambition fulfilled. In 1171, a mere year after Strongbow arrived, he died. On his death the kingship of Leinster fell to Strongbow, through Aoife. He was now in total control of the province.

The marriage of Strongbow and Aoife

The marriage of Strongbow and Aoife

Rory O'Connor, however, while weakened was still a threat, and the Normans under Strongbow only held Dublin, Wexford and Waterford, a relatively small percentage of the whole of Ireland. In 1171 O'Connor laid siege to Dublin, hoping to starve Strongbow's people into submission. The Irish were not experts at siege: they had no clue what siege engines were, and merely surrounded the town with their troops. After a weak attempt at a truce, wherein his promise to swear fealty to the High King and renounce the feudal ties to his king were rejected, Strongbow engineered a daring attack by day. He literally (so the tales say) caught Rory O'Connor and most of his men bathing in the river Liffey. Unprepared (as you are, when naked) for the assault, the Irish were routed and the story spread of Strongbow's cunning and guile, bringing more Irish lords over to his side and further weakening Rory O'Connor.

But all was not well for Strongbow. He had taken Ireland (well, Leinster) at the command of and under the auspices of King Henry, on condition he hold it as a vassal of the English king. When he offered to renounce this fealty, even though the offer was dismissed, it would not take long for the news to reach Henry. And news of attempted treachery and betrayal never sits well with kings.

Henry II and the arrival of the English

Henry II and the arrival of the English

As already related, Henry was no friend to Strongbow, and did not select him for the task of helping MacMurchada regain Leinster; he told the Irish king he had licence to seek aid in his royal name, but did not mention Strongbow. Henry and the Earl of Pembroke had already butted heads, and the king certainly did not trust Strongbow. When his vassal seemed on the point of turning Ireland into a staging point for a possible attack against his former king – which may or may not have been in Strongbow's mind; remember, his roots went back to the Vikings, whose ethos had always been conquest – he decided it was time for him to take a personal hand in things. With the war in France over he was able to turn his attention to this annoying little island, and see how it might become a problem.

In October of 1171, a mere five months after the death of the man who had unwittingly provided him the excuse he needed to come to Ireland, and only two months after Strongbow had married Aoife and taken the kingship of Leinster, King Henry II arrived in Waterford with a massive fleet of four hundred ships. This was a proper invasion, intended to bring the Irish church into line with the Crown and to subjugate the population to its rule. It was the beginning of an occupation which would last well into the twentieth century.

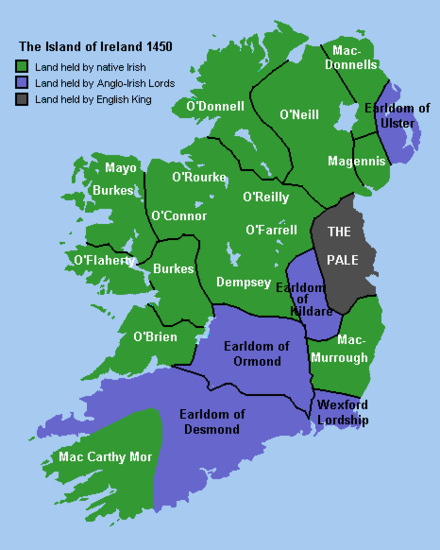

Although Henry II only stayed in Ireland for six months, he ensured that his power and authority there was unquestioned, securing fealty from Irish chieftains – including, eventually, the self-styled High King, Rory O'Connor, who was granted the province of Connaught – and conferring land on barons from among Strongbow and his own contingents, English nobles who were awarded Irish counties, such as Meath, Westmeath and Cavan, which were granted to Hugh de Lacy, one of the king's trusted advisers. Henry's son, John Lackland, who would become King John on the death of his father in 1199, presaging a new century which would be plagued by deprivation and bad governance, rebellion and unrest, and give rise to the legend of Robin Hood, was named Lord of Ireland. And yes, he was the same King John who signed the Magna Carta – not

Encarta, kids: that's a whole different thing.

An interesting and indeed important historical event around this time was when Rory O'Connor, former High King of Ireland and now content (without any real choice) to have Connaught for his realm, married off his daughter to Hugh de Lacy, which not only strengtened ties between Ireland and England but became the point in history to which the direct involvement of the English in Irish affairs can be traced. The status of Ireland was changed from a free independent land to that of a lordship of the English Crown, bringing it under direct rule of the English king. Meanwhile, John de Courcy, another English baron who had arrived with King Henry, set out for Ulster and took various towns there, setting himself up as the ruler of Ulster. He had done this, however, without the blessing or even the permission of the King, who then sent Hugh de Lacy to rein him in.

The story goes that de Lacy was told that de Courcy was such a religious man that the only time he would take off his armour and shield (which, it was said, he even slept in) was on Good Friday. On that most holy of days, he could be found in the church, praying, and defenceless. Caring, it would seem, nothing for the sanctuary of the church, de Lacy sent his men to apprehend the earl of Ulster, who was taken after a ferocious fight. Hugh de Lacy was then granted the earlship in his place by Henry. De Courcy would spend much of his life in exile, and after an abortive attempt to retake his holding in Country Down, but was repulsed and late imprisoned by the king.

In addition to their fierce knights and terrifying longbows and crossbows, the Normans were superior to the native Irish in that they believed in towns and settlements, and built castles, many of which survive today. Notable among these are Dublin Castle, which served as the centre of English power in Ireland right up to the Rising and until Ireland's independence was procured in 1922. They introduced the idea of towns and cities to Ireland, though their superior weapons and charging knights could become bogged down in the mazy Irish landscape, which the Irish, familiar with, could navigate much more easily and use to set traps for their enemy. The Normans also introduced the idea of proper commerce to Ireland, with trade guilds set up. These were basically clubs, but vital to be part of. If you were not, for instance, part of the baker's guild, you could not bake. If you weren't a member of the carpenters' guild, you couldn't be a carpenter. And so on. As a way of excluding Irish tradesmen, membership of any guild was restricted to those of English name and blood. The very first “No Irish!” sign, as it were, something that immigrants down the centuries would see and turn away from.

Dublin Castle today

Dublin Castle today

And so the subjugation of the Irish began in earnest: their lands were taken over by Norman barons and they were forced into serfdom to the lords. As the thirteenth century drew to a close, over sixty percent of the land of Ireland was occupied, owned and held by Norman lords loyal to the Crown, but essentially allowed a modicum of autonomy, as the feudal system was introduced to the previous independent island. Franciscans, Dominicans and Augustinian orders moved in to “civilise” the Irish Church, taking over the monasteries and building new ones, and stamping their authority – and the authority of the King and the Pope – on the abbeys and monasteries that had enjoyed such independence for so long.

In England, the reign of King John had passed by now and he had been supplanted by the weak Henry III and then by Edward I, who came to be known as “The Hammer of the Scots” (you've seen

Braveheart, haven't you?) for his implacable suppression of the Scots' attempt to gain independence. He further impoverished Ireland by taking thousands of fighting men and sending them to war against the Scots, at Ireland's expense. Scotland had her revenge though when the king's son and successor, Edward II, lost to Robert the Bruce at Bannockburn in 1314, and

his own son Edward Bruce then tried to take Ireland from the Normans, at the behest of the Irish in Ulster. Ireland sent a famous letter to the Pope,

The Papal Remonstrance, decrying the conditions the Normans foisted upon them, and asking His Holiness to intervene, but he never did. Edward Bruce landed in Ireland in 1315 and though initially he had many successes, and was in fact on the verge of complete victory, nature conspired to overturn his plans.

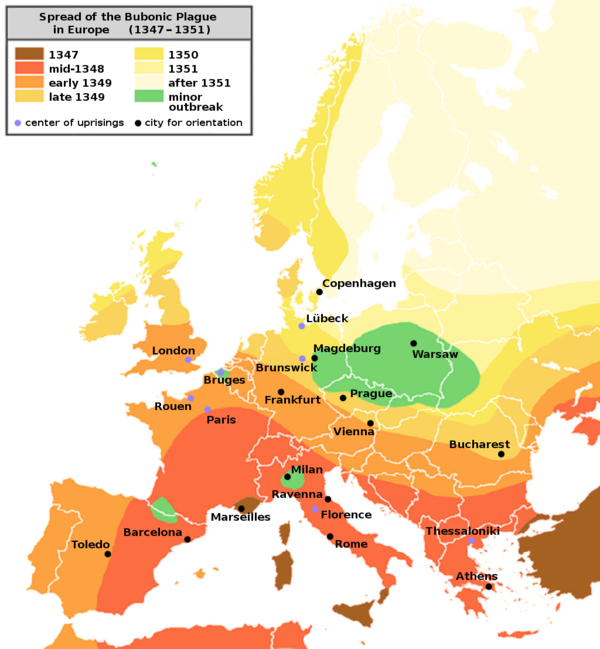

He failed, mostly due to the terrible famine that was sweeping across Europe at that time, and which had reached Ireland in 1316, but the power of the Normans was beginning to wane. Irish power was being re-established by the middle of the fourteenth century, by which time Ulster and most of Connaught were again under the control of the Irish chieftains, and even the Norman invaders were beginning to “go native”, adopting Irish customs and language and laws, intermarrying with Irish women and considering themselves, as the quote went, “more Irish than the Irish themselves”, resulting in the Statutes of Kilkenny, laws passed by British Parliament which made adopting Irish customs, language and laws illegal.

I'd like to digress here for a moment to recount a very funny story our history teacher told us, to illustrate how sometimes, winging it can be hilarious. He related how one question on the history paper at an exam was “What were the Statutes of Kilkenny?” and one clever dick wrote “The Statutes of Kilkenny were tall stone figures, twenty feet high, and Americans from all over the world came to see them”!

Yeah, well I thought it was funny. Anyway, back to the real text.

With the defeat of Edward II at Bannockburn, Robert the Bruce had achieved for the first time that which no other Celtic country could boast: he had taken on England and won. The mythical infallability and superiority of English forces developed an important crack, one the Irish would worry at and exploit over the next few hundred years. The power of the English in Ireland would be further weakened, as would all reigns and all kingdoms across Europe, by a force that not even kings or popes could stand against, and which was believed by many to be a punishment from God.

Newgrange is therefore more or less accepted as one of the oldest monuments in the world today. It is probably well known (but I'll tell you anyway in case you aren't aware) that it is more than just a simple burial chamber. It is of the type known as a “passage tomb”, due to its long narrow approach to the burial chamber itself.

Newgrange is therefore more or less accepted as one of the oldest monuments in the world today. It is probably well known (but I'll tell you anyway in case you aren't aware) that it is more than just a simple burial chamber. It is of the type known as a “passage tomb”, due to its long narrow approach to the burial chamber itself.

But seriously, it's a hard concept to get: how can you have one god who has a son and another part of him, each separate yet of the same being? Patrick explained this by picking a shamrock, and showing that though it has three leaves, they all rise from the one stalk. And so the people finally got it, and the shamrock became one of our most treasured plants, and indeed the emblem of our country.

But seriously, it's a hard concept to get: how can you have one god who has a son and another part of him, each separate yet of the same being? Patrick explained this by picking a shamrock, and showing that though it has three leaves, they all rise from the one stalk. And so the people finally got it, and the shamrock became one of our most treasured plants, and indeed the emblem of our country.

To add to this, the north/south split had already been well in evidence in Ireland, with the powerful O'Neill family ruling pretty much all of Ulster, and casting greedy and ambitious glances South, and if O'Neill (known as “The” O'Neill, to denote the head of the family and the man in power, to differentiate him from the many other O'Neills scattered throughout Ulster) believed himself king of Ireland (High King), while there was no actual king in the South, his authority was not acknowledged there, though his southern cousins did control much of it.

To add to this, the north/south split had already been well in evidence in Ireland, with the powerful O'Neill family ruling pretty much all of Ulster, and casting greedy and ambitious glances South, and if O'Neill (known as “The” O'Neill, to denote the head of the family and the man in power, to differentiate him from the many other O'Neills scattered throughout Ulster) believed himself king of Ireland (High King), while there was no actual king in the South, his authority was not acknowledged there, though his southern cousins did control much of it.

Yeah, well I thought it was funny. Anyway, back to the real text.

Yeah, well I thought it was funny. Anyway, back to the real text.

Hybrid Mode

Hybrid Mode