While most of the history of the Great Famine is steeped in tears, tragedy, pain and anger, death and disease, despair and emigration, and a burning need for justice - or if that wasn’t possible, revenge would do - it is illuminating to just recount the many ways people across the world came to the aid of Ireland, many doing the little they could (which quite often means more than huge donations from banks and corporations and kings) and everyone trying to help a country that was really teetering on the edge of extinction. Irish-Americans of course dug deep, and even future President Abraham Lincoln, at the time a mere Congressman, donated ten dollars (doesn’t seem much, but that’s about three hundred in today’s money, and that was a lot for a private individual to contribute to any cause) while the president at the time, Jame Polk, gave five times that much. Choctaw Indians, who had just been resettled, read, forced to leave their native lands on the horrible journey of despair which came to be known as “The Trail of Tears”, gathered together a huge sum at the time, 170 dollars, which you can see yourself is more than three times what the President of the United States gave, almost five grand today.

Every country helped. Russia, Italy, Venezuela, South Africa, Mexico, Australia, while the British Relief Association, on foot of a letter from Queen Victoria urging donations to help the Irish poor, raised almost seventy percent of the total given by the British, over £390,000. It’s also really heartening to see that in America, religious groups put aside their differences as Jews, Methodists, Presbyterians, Lutherans, Episocopalians all banded together to help raise funds and send ships of food and goods to Ireland, and in South Carolina it was said that "The states ignored all their racial, religious, and political differences to support the cause for relief.”

Let’s be honest here: you can’t see that happening today, can you? In fact, it doesn’t. Other than going back to Bob and Live Aid as I mentioned at the start, we don’t see such universal comings-together in the name of starving people. We have, unfortunately - and this very much includes we Irish, who should know better - got so used to famine in general and to seeing pictures of starving children on our television that we just ignore it; another humanitarian disaster, terrible, wish there was something we could do, poor kids, change the channel. Not only that, but sharp religious and political differences have never been so at the forefront of politics all over the world now that such setting aside of enmities and prejudices and old rivalries seems, and in fact is, impossible to envisage. You only have to look at the ongoing migrant crisis to see how a stream of human beings, dispossessed of their homes and fleeing war zones, elicits nothing more than lip service and a shake of the head. Times have most definitely changed, and not for the better.

There was, however, another, less noble and somewhat more sinister practice involved in some of the charity given, where certain groups used the offer of food as an inducement, or rather put a condition on it. This was called “souperism”, from the practice of Protestant Bible schools setting up soup kitchens, to which anyone was admitted and would be fed, as long as they were prepared to learn the Protestant way of things. It amounted in effect to blackmail, a case of “if you want to eat worship our god”, and became a bone of contention with Catholic families, who felt they were being asked to choose between their religion and their family, which they were. Those who accepted the deal were looked down upon by those who did not, their full belly no guarantee the Catholic Devil would not drag them all down to Hell for such betrayal. They were called “soupers”, or “the ones who took the soup”, and both became a real insult in Catholic Ireland, similar to “taking the King’s shilling”, i.e., adopting the English way.

It is however important to understand that, like a lot of claims made about this or that by this or that injured party, and meaning to do my own countrymen no disservice, the practice of “souperism” is reported to have been quite minimal; many, in fact most schools, even many of those operated by Protestants, offered food and relief to people without any condition attached, though because of either the hyperbole of newspaper reporting, the inbuilt, deep-seated hatred and distrust of Catholics for Protestants, or to help special interest groups fan up that hatred and outrage, or a combination of all three, and maybe more, the word went around at the time that all Protestant schools were engaging in this form of spiritual blackmail, and as a consequence, even if the school in question was not, Catholics feared sending their children there in case they ended up being corrupted and forced into the wrong religion. As well as this, with or without riders, Protestant faith does not observe Good Friday, and so their schools would serve meat soup on Fridays, when Catholics were supposed to abstain from meat. This was another reason why they were shunned by the Irish, and why many children went hungry, the health of their everlasting soul deemed more important than that of their temporary body.

To some extent, you could say the term “souper”, used not for those who provided the food under these restrictions, but for those who partook of it, became almost as much an insult as “collaborator.” The idea was of course that those who gave in and accepted the charity - even if it was a case of their doing the reverse of above, and putting the health of their children - their very survival, their lives - ahead of religious matters were seen as giving in, as bowing down and all but accepting the Protestant faith. That wasn’t true of course; these weren’t, to my knowledge, boarding schools, and the children’s parents could correct any erroneous notions put in their heads by the teachers by explaining they had to endure this in order to get food, but that what they learned in these schools was nonsense.

Nevertheless, the very act of crossing the threshold of a “souper” school made the parents responsible in the eyes of other Catholics, and traitors to their religion. They would be ostracised, in some cases British soldiers even having to be called in to protect them from their furious neighbours. How incredible, that even at death’s door with hunger, people could still find reasons to fight over religion. If it had been me, and Satan had opened up a soup kitchen, I’d have had my kids down there. But the Catholic religion teaches that the body is nothing but a shell, and everyone should be more concerned about how their soul will fare after death. Only here for a short time, not a good time, could be a motto for the Catholic Church, and its priests joined in the condemnation, loudly lambasting known soupers from the pulpit. With full bellies, no doubt.

Nice as it is, and a change, in the midst of so much horror and death, to talk about charity and kindness shown to the victims of the Great Famine, it is sadly inevitable that we have to return to the darker, more prevalent side of the crisis, and specifically to the ones who, it could very well be said, precipitated and then exacerbated the misery by refusing to recognise, or care about, the depth of the poverty of the people they demanded rent from. All they cared about was their pockets, and yeah, you’ll not be surprised to hear I’m talking about the landlords and the middlemen, the scourge and curse of the Irish poor, and almost the incarnation of evil with very little if anything to mediate their greed, lack of compassion or even humanity. Let’s shuffle into the rogues’ gallery to meet some of them.

Marcus Keane

Feared and hated by thousands as “the exterminator-in-chief”, Keane was the son of a landowner whose family had come over to Ireland almost with King Henry II, and had been in Clare since the thirteenth century. He worked as an agent for some of the bigger landlords - the Conynghams, the Vandeleurs and the Westbys - but had by degrees built up his own landholdings until he owned about 4,500 acres. Consider that: if each tenant farmer, as noted earlier, had a quarter acre to farm (they didn’t; many had larger, but not much. This would have been the average) then Keane’s landholding would have supported - in the loosest possible sense - over 18,000 families. He got married the year the Great Famine struck, 1847, no doubt a lavish wedding feast that could have fed most if not all of those 18,000. He would not have cared. From the epithet above, you can guess he was not a nice man.

A hardline Protestant, he refused the local parish priest, Father Michael Meehan, permission to build a Catholic church on his land in Kilbaha, as his master, the landowner and his father-in-law, Edward Westby, did not want such a focus for Catholic worship. In defiance, Father Meehan built a small mobile church called the

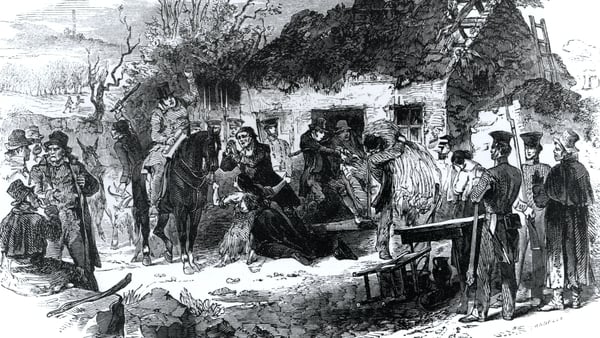

Little Arc on the foreshore, and this became a focus for resistance to the tyrannical landlord. But this was mild. Through 1847, at the worst heights of the Famine, Keane evicted twelve families from his land in Garraunnatooha, the most famous - or infamous - of these being Bridget O’Donnell and her family. Bridget was pregnant at the time, and her husband worked a small farm of five acres from Keane. He had purchased oat seeds from the landlord, grown the corn and harvested it, then had it confiscated by Keane’s agent, Dan Sheedy. Sheedy had then arrived with a gang to evict the O’Donnell’s. Owing to the trauma, Bridget had given birth to a stillborn baby and received the last rites from Father Meehan, though whether she survived, died or what happened to her afterwards is unknown.

Also unknown, and of some small comfort, is what happened to Keane’s body after he died. Supposed to have been interred in his own private mausoleum, he rather inconveniently (but not before time, if you ask me) died before it was completed, and so was instead laid to rest in the vault of the Burkes, where he had had the body of his governess, Margaret Barnes buried. When the new tomb was ready his son came to move the body but found to his dismay that it was gone, along with that of the governess. A search party found nothing, and it would be a full seven years before the two corpses would be discovered to have been buried nearby in another plot, with the nameplates removed from their coffins. Perhaps the ghosts of the victims of the Irish families he treated so reprehensibly had their revenge from beyond the grave?

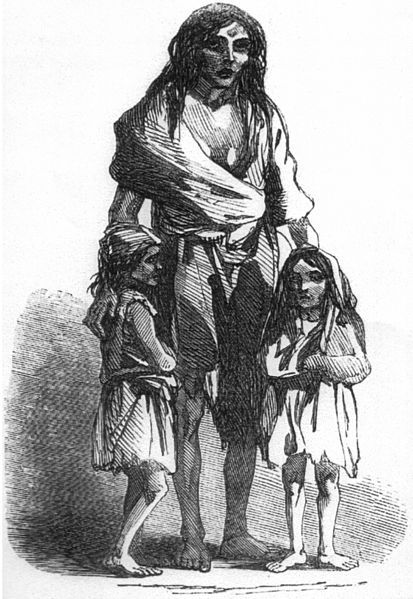

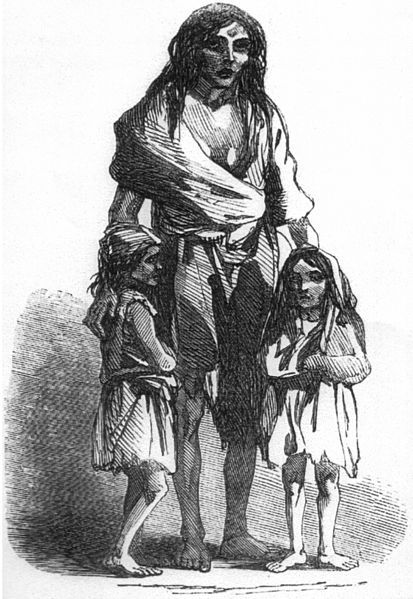

His kind of brutish, unprincipled, evil behaviour would not have been typical, in fairness, of every landlord in Ireland, but the few who were decent and treated their tenants well would certainly have been in the minority. Bridget’s plight came to national attention when an engraving of her appeared in the

London Illustrated News, the picture like something out of Dickens’

A Christmas Carol, where Scrooge is shown the spectres of want and ignorance skulking beneath the cloak of the Ghost of Christmas Present. The pathos and pity such a figure elicited threw into sharp relief the disgraceful practices of Irish landlords, Keane being accused of being over-zealous in his eviction of tenants from Klirush, especially in the local Poor House, from 1848 - 1849, and a parliamentary committee was convened to look into the allegations, which had been brought to British officials by the Poor Law inspector for the Union, Captain Kennedy. As a result, a reporter was despatched from the

London Illustrated News, and he brought back this harrowing account.

“It is a specimen of the dilapidation I behold all around. There is nothing but devastation, while the soil is of the finest description, capable of yielding as much as any land in the empire. Here, at Tullig, and other places, the ruthless destroyer, as if he delighted in seeing the monuments of his skill, has left the walls of the houses standing, while he has unroofed them and taken away all shelter from the people. They look like the tombs of a departed race, rather than the recent abodes of a yet living people, and I felt actually relieved at seeing one or two half-clad spectres gliding about, as an evidence that I was not in the land of the dead.”

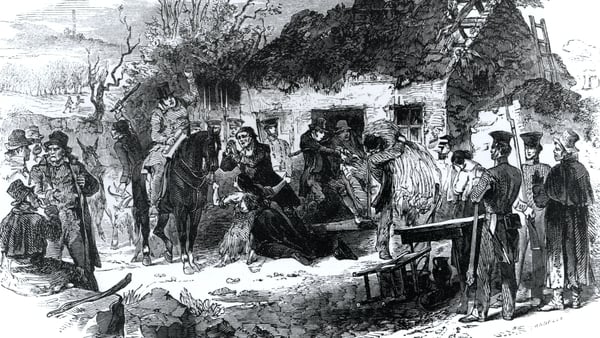

Perhaps it did English people some good to see the way their representatives were treating the Irish people in their power, perhaps they didn’t care, but the engraving of Bridget O’Donnell and her pathetic family remains one of the striking images of the Great Famine, akin perhaps to that picture of the GIs raising the flag at Iwo Jima, or the Chinese student facing the tank in Tiananmen Square. Even when the evicted tenants did their best to set up makeshift shanty towns, huts of mud and sticks called “scalps”, near to where they had only just recently lived before being thrown out by an uncaring landlord, they were not safe. This account tells of how one woman lost not only her second, lean-to home, but also her child, no doubt the work of the “wreckers”, bands of tough, young, ill-educated poor yobs who worked for the landowner or his agents, and must have been equated to the Yeomanry of earlier decades.

Having put together their scalp, the woman’s husband went off somewhere while she visited a “neighbour” about 100 yards away. While she was out of the scalp it was set on fire. She ran back to try to save her child, but was only in time to see them being ‘taken out of the scalp on a shovel, all burnt to death, by a man named Michael Griffin. I am sure that the scalp was set on fire by some person or persons, for it could not otherwise take fire’ Utter scum. Not content with destroying the family’s poor home and kicking them off the land, they burned down their makeshift one, and never bothered to check if anyone was inside. True, they probably did not mean to kill anyone, but I doubt the fact they did caused them any sleepless nights.

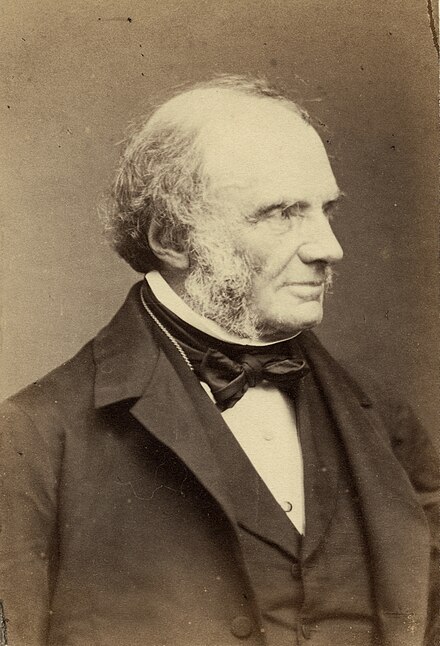

George Bingham, 3rd Earl of Lucan(1800 - 1888)

George Bingham, 3rd Earl of Lucan(1800 - 1888)

Another serious offender was a nobleman, an earl, who was so dismissive of and uncaring of his tenants that he snapped he “would not breed paupers to pay priests”, had over 300 homes knocked down, making over 2,000 people homeless in Ballinrobe, Co. Mayo, and even went so far as to destroy their only alternative means of support, the workhouse. He, too, earned the nickname “The Exterminator” among the Irish. For his crimes against humanity he was appropriately punished, being promoted from colonel to major general in 1851. He was not a popular man, enraging the local garrison by demanding their barracks windows be blocked up, as he snarled the men were looking at his wife as she took her walks in the garden of his house, which the barracks overlooked. On arriving in Ireland he dismissed his land agent, a popular man called St. Clair O’Malley, and immediately set about enforcing the kind of reputation he had enjoyed in the army, as a martinet and a bully.

One one occasion, his tenants in Castlebar, believing him to be in London, burned him in effigy, and then had to scatter in panic as he rode up upon them, shouting “I’ll evict the whole bloody lot of you!” An interesting fact here is that after returning to England, he was posted to the Crimea and actually led the doomed and pointless but very famous Charge of the Light Brigade. Odd to read that when he came back to Castlebar he was welcomed, the city illuminated in his honour. As a postscript, it seems his son was far better than his father, returning to Mayo and being much fairer with the tenants, providing education for Catholic children and allowing the tenant farmers to buy their land.

Denis Mahon

A major in the British army, he secured landlordship of Strokestown, in Co. Roscommon, by having its previous owner, his uncle Maurice, declared mentally unfit and taking over. His first move was to inform the tenants there that rents, which had lapsed during the tenure of his uncle, were now due, including all arrears, going back three years. Obviously nobody could pay this sort of money, and a strike was quickly organised, whereby everyone refused to pay. Mahon responded with mass evictions, but the families returned to their homes, he would have them evicted again, they would return, and the whole thing took on the complexion of a crazy game of roundabouts.

Mahon broke this cycle by ensuring those evicted were moved onto chartered “coffin ships” bound for Canada. Almost everyone on board died or were refused admittance, the news coming back to their families in Roscommon. This led to an attack on Mahon in which he was killed on November 2 1847, the murder sparking off a tinderbox of similar killings of landlords, and threats against others. Not surprisingly, the Ascendancy back in London were quick to jump upon this as a Catholic plot against Protestant landlords, without bothering to consider how brutal a man Mahon had been, and four men were eventually accused of his death, two hanged, one sentenced to transportation for life (which, given the coming years of famine, may very well have saved his life. Or he may have died over there, but at least he would have had more of a chance than those he left behind) and one who escaped to Canada.

The final word on evictions can perhaps be best left to the Bishop of Meath, The Most Reverend Thomas McNulty, who wrote, in a pastoral letter to his congregation:

Seven hundred human beings were driven from their homes in one day and set adrift on the world, to gratify the caprice of one who, before God and man, probably deserved less consideration than the last and least of them ... The horrid scenes I then witnessed, I must remember all my life long. The wailing of women—the screams, the terror, the consternation of children—the speechless agony of honest industrious men—wrung tears of grief from all who saw them. I saw officers and men of a large police force, who were obliged to attend on the occasion, cry like children at beholding the cruel sufferings of the very people whom they would be obliged to butcher had they offered the least resistance. The landed proprietors in a circle all around—and for many miles in every direction—warned their tenantry, with threats of their direct vengeance, against the humanity of extending to any of them the hospitality of a single night's shelter ... and in little more than three years, nearly a fourth of them lay quietly in their graves.”

Linear Mode

Linear Mode