There's an old Irish saying (not really, it's a joke but we should adopt it): "Important" in Ireland means "what's yer hurry? There's time for another pint!" and as for "urgent", see under "important"! Although the circumstances under which this journal - and all my others - have been left languishing for next to a year are far from funny, in a way it fits. At any rate, time to head back to that dark time in Irish history when the only people who weren't dying of starvation were the rich and the English.

Welcome back,

a chairde (friends) to the Great Famine.

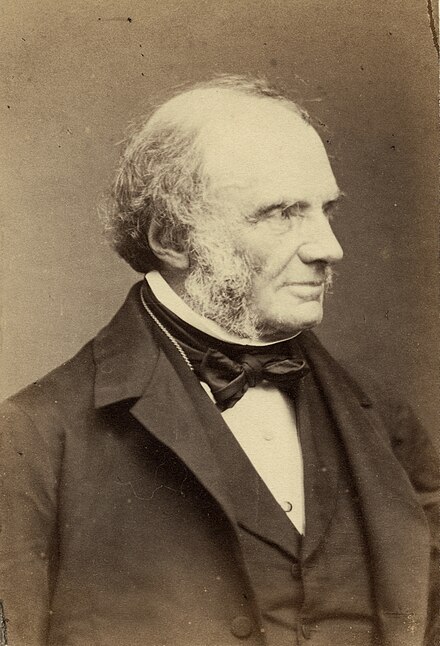

But first things first. Let’s, then, before we go into the Great Famine in detail, as I promised we would, look into this guy who took over from Peel, and so was surely at least partially responsible for all the deaths in Ireland at the time.

John Russel, 1st Earl Russell (1792 - 1878)

John Russel, 1st Earl Russell (1792 - 1878)

It will come as a surprise to nobody to read he was a rich bastard, born into one of the richest and most noble families in Britain, his ancestry stretching back to the seventeenth century, and despite - or perhaps due to - his father being Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, he had no time for the Irish. Few British politicians did, all of them being Anglican Protestants and the hatred of both Catholics and, as the main exponent of that religion, Irish, almost hard-coded into their DNA by now. Like a lot of the young aristocracy, Russell’s seat in the House of Commons was literally given to him by daddy, the Duke of Bedford instructing his cronies to return his son (never understood that phrase: someone who is standing for the first time for a seat can be returned - doesn’t something have to be somewhere first before it can be returned?) despite his not even being of age to take the seat. Wasn’t even interested in politics, and only entered due to a sense of duty. Fu

cking rich bastards. One law for etc.

But maybe I’m wrong here. Seems he authored the Sacramental Test Act, which sought to remove the restrictions on Catholics and Dissenters, allowing them to hold public office. Hmm. And the bill passed. He also argued against the tithes in Ireland, suggesting that a proportion of the funds should go to help educate the Irish poor. Yeah. Seems like I have got him wrong. At least in the earlier days - this was around 1834 - he does look to have supported the Irish cause as much as would have been possible for him. He also got through the Marriages Act, which removed the requirements for Catholics to only marry in Anglican churches, and even helped reduce the amount of crimes punishable by death in Britain, paving the way for the almost-abolition of the death penalty for any crime but murder.

In opposition at the end of 1845 he supported Peel’s attempt to overturn the Corn Laws, so it seems odd to me that, once in power, he refused to help the Irish during the Famine. Let’s see. Came to power, as I said above, mid-1846, and seems to have made some efforts but realised they have failed (probably worried that the cost outstripped the political capital he would have to sacrifice in “siding with the Irish” maybe) and with a small majority barely keeping his government in power, and a financial crisis also to deal with, he just turned to other things. I’m sure a million Irish understood.

Men at work: The Public Works

Men at work: The Public Works

Although the idea behind creating a system of public works was to allow people to earn money to buy food, there were a lot of drawbacks to this idea. Firstly, we’re talking here about people who could barely stand, never mind lift a shovel or pick, and not just the men: wives and children also worked. Apart from the child labour laws being entirely non-existent at this time, the simple arithmetic of it was that the more people in your family who worked, the more you got paid, and so everyone worked. Apart from anything else, would you want to be starving at home while your parents dug ditches or built roads? But that was all well and good until one bright spark decided hey, I’ve got an idea! Instead of paying these Oirish louts a day’s work for a day’s pay, let’s just pay them for the actual work they do. That will weed out the lazy and feckless among them, or Her Majesty isn’t Empress of India!

Great. So now by definition the strong got to eat, while the weak, unable to work, or at least unable to work as well as the stronger ones, would be paid less, or even nothing. It has been said, and I can see why, that far from actually creating relief these public works were all but slave labour, working people to death, and a percentage of the mortalities in Ireland at this time can certainly be put down to those who literally dropped dead at their work. Even if you did earn enough for a few scraps of food, you still had to travel some distance - on foot of course - with your stomach grumbling, no guarantee you would even reach the store before you just collapsed, both of hunger and weakness.

The other point about the works is that they were largely pointless, projects devised and put into operation for no reason other than to afford work to people. While this is all very philanthropic on the very skimmed surface - it would have been more Christian, would it not, to have given out bread free, as was happening in Europe? - it left Ireland with a bunch of roads and ditches and harbours and stuff which she did not need. They were, as Liam Neeson notes in the wonderful two-part documentary

The Hunger “roads to nowhere”.

The Repealer tries to Repel: O’Connell’s efforts to stave off the Famine

Leading a deputation including the Duke of Leinster, Lord Cloncurry and the Lord Mayor of Dublin, Daniel O’Connell, who saw the Devon Commission as a pointless and one-sided endeavour, made up entirely of landowners with no representation from tenant farmers, went to the Lord Lieutenant in November 1845 with a petition and ideas, including opening up the ports to foreign corn, the end of the use of grain in distilleries and the prohibition of the export of foodstuffs. He also asked for the practice of “tenant right”, in operation over the border in Ulster, which gave the tenant farmer the right to compensation for any improvements he had made to the land he worked, to be introduced in the South. But Lord Haytesbury shrugged and told him not to be worrying; things were not as bad as they seemed.

O’Connell also lobbied - perhaps over-ambitiously, to say the least - for the repeal of the Act of Union, as he maintained that an Irish parliament would have instigated his ideas, closing the ports to export and opening them to import, and providing relief and work for the starving people of his island. Needless to say, this was shut down, if not actually laughed at. The idea that the British would allow Ireland to leave the Union in a sort of nineteenth-century Eirxit, just to save a few million lives, was ludicrous in the extreme. It’s hard, under the evidence of such intransigence and apathy on behalf of the British, to challenge the words of John Mitchell, Irish nationalist, poet and repeal advocate, quoted at the beginning of this piece. If the Great Famine was not a deliberate attempt at ethnic cleansing and genocide, it’s difficult to defend the notion that the British used it to try to accomplish their goal of pacifying Ireland and reducing significantly the number of Catholics living there.

It’s also a little hard to comprehend why the British government did not order the closure of the ports, as this had been British policy a hundred years ago, in 1782-83, and it worked. But showing the innate pig-headedness and casual cruelty and lack of compassion of the Whig government, the Gregory Clause of the Poor Law stated that - hold on here a moment. This is what I don’t understand. I assumed this guy Gregory (William H.) after whom the Clause is named, was some ultra-hardline Protestant, but then I read that he was sympathetic to the Catholic cause AND a friend of Daniel O’Connell! So how then could he have authored a clause in the Act which prohibited relief to anyone with a farm of a quarter of an acre or more? That’s approximately 10,000 square feet, or 1000 feet by 1000. Try to picture that. If your sitting room or bedroom is about maybe 15 feet (let’s assume, for the sake of my poor maths, that it’s ten) then push ten of them together and you have one side of the farm, another ten across and that’s the size of the land you have to work on. That’s not a farm; that’s not even a plot. That’s an allotment, and not usually even of good land.

So the idea of the Gregory Clause was that if you had this quarter-acre or more of land you worked, and it became necessary for you to seek relief because you couldn’t grow anything on the land you rented from the fat bastard landlord as, you know, potatoes were being blighted and there was a famine on and all, you had to sell your land in order to qualify for the relief! It sounds to me like in order to get the money for food you had to sell your house. This ended up creating a phrase, “passing paupers through the workhouse”: in effect, you went in a man and came out a pauper, with everything taken from you. And who knew what piddling amount they would condescend to give you in relief? Very little, surely. Not worth the land you had spent perhaps your life working on, which now went back to the callous landlord, who could rent it to someone else.

And then the government passed the Encumbered Estates Act, in 1849, which allowed for the sale of these lands at a knockdown price. The lands were of course then bought by speculators, who didn’t want no stinking tenants fouling the place up and moaning about being poor and hungry: who wanted to hear that, even if they weren’t actually there to hear it themselves? One must maintain some standards, don’tcha know? So the tenants were often evicted - and could be, without the slightest cause or reason, and with no recourse by the tenants to the law - so that the new owner could raise livestock or whatever they wanted to use the land for. Between 1849 and 1854 over 50,000 families were evicted. That’s one-twentieth, or five percent of the lives lost in the Great Famine. I said it before, and I’ll say it again: bastards. No wonder we hate them.

Still, before get too anti-British, let’s consider the military response. Between 1846 and 1847 the Royal Navy transported supplies into Cork and other ports in Ireland, the government having realised by January that the idea of leaving the Irish to it was not working duh, and two days after Christmas 1846 Sir Charles Trevelyan, in charge of relief in Ireland, ordered all available ships to assist in the effort. Royal Navy surgeons were also despatched in February 1847 to assist in rendering medical aid and to ensure all burials were undertaken with proper health and sanitation procedures followed.

While the general perception has been that people starved as food was exported from the country - and it was - statistics now seem to back up the fact that less went out than came in, but that complications with financing the relief effort through the Poor Laws, and the need to feed cattle, resulted in there being less food for the starving families, making it necessary for food to be sold so as to enable landlords to pay the rates and thereby fund the workhouses. Father Nicholas McAvoy, Parish Priest of Kells, wrote in

The Nation in October of 1845:

On my most minute personal inspection of the potato crop in this most fertile potato-growing locale is founded my inexpressibly painful conviction that one family in twenty of the people will not have a single potato left on Christmas day next. Many are the fields I have examined and testimony the most solemn can I tender, that in the great bulk of those fields all the potatoes sizable enough to be sent to table are irreparably damaged, while for the remaining comparatively sounder fields very little hopes are entertained in consequence of the daily rapid development of the deplorable disease.

With starvation at our doors, grimly staring us, vessels laden with our sole hopes of existence, our provisions, are hourly wafted from our every port. From one milling establishment I have last night seen not less than fifty dray loads of meal moving on to Drogheda, thence to go to feed the foreigner, leaving starvation and death the sure and certain fate of the toil and sweat that raised this food.

For their respective inhabitants England, Holland, Scotland, Germany, are taking early the necessary precautions—getting provisions from every possible part of the globe; and I ask are Irishmen alone unworthy the sympathies of a paternal gentry or a paternal Government?

Let Irishmen themselves take heed before the provisions are gone. Let those, too, who have sheep, and oxen, and haggards. Self-preservation is the first law of nature. The right of the starving to try and sustain existence is a right far and away paramount to every right that property confers.

Infinitely more precious in the eyes of reason in the adorable eye of the Omnipotent Creator, is the life of the last and least of human beings than the whole united property of the entire universe. The appalling character of the crisis renders delicacy but criminal and imperatively calls for the timely and explicit notice of principles that will not fail to prove terrible arms in the hands of a neglected, abandoned starving people.”

It is fair though to say that the Famine opened hearts, and wallets, and many charitable

donations did give aid to the hungry. Perhaps surprisingly, English Protestants accounted for the highest amount of Irish famine relief outside of Ireland, Pope Pius XI issued an encyclical which called on the entire Catholic world to help in the relief of their Catholic brothers and sisters in Ireland, and a rough figure for donations - including about a half million from Britain - totalled in the area of £850,000. I mean, in real terms, that’s less than a pound per person who died in the Famine, but it does at least show that there was an appetite for aid and that Ireland did not stand entirely alone as the rest of the world looked on. And remember, too, that other areas of Europe - Belgium, France, even England - had suffered their own destruction of crops, though none of these hardships compared in any way to the Irish Famine, which is still seen as the greatest humanitarian disaster of the nineteenth century.