Timeline: 18th - 19th century

Perhaps it was the changing attitudes or techniques in painting by the eighteenth century, but it’s interesting that Thomas Stotthard’s

Satan Summoning His Legions pulls away entirely from the traditional image of the Devil as the goat-monster-demon, representing him as very human, almost heroic, in silver armour and with no hint of horns, tails, claws or even beard. If you were to look at the painting without knowing its subject, you might convince yourself it was, I don’t know, some Roman general or a hero out of Greek myth. It’s quite extraordinary, and I do find myself wondering how it was received, painted as it was in 1790, only a hundred years after the infamous Salem witch trials.

Well, reading a little about him I can see that despite the rather German-sounding name, he was in fact English, and worked as an illustrator as well as an artist, painted scenes from classical mythology, Shakespeare and famous figures such as George Washington, Margaret of Anjou and King George III, and was a friend of William Blake. So it would appear that the above painting was a departure for him, not something he would normally turn out, and in that manner I suppose based pretty much on the historical and military figures he had painted, thereby I imagine explaining why his Devil is so, well, human. I suppose he hadn’t either the taste for painting monsters, nor any real need to. Nevertheless, I would say his work stands as a very unique and almost - perhaps not intentionally - complimentary image of the Lord of Lies. Oddly, in a list of seventy-four of his paintings I can’t find this one, so perhaps it’s not one of his better-known or regarded works.

And of course I’m wrong. I’m not at all surprised; I am no student of art and couldn’t tell a Botticelli from a jelly botty, so no gasps of astonishment as I realise that this very ideal of Satan was in fact also used by another Thomas, this time Thomas Lawrence, who in 1796-7 produced the very same subject with the same title (I think these are both depicting a scene in

Paradise Lost by John Milton?) where Satan is again a powerful, classically-beautiful man, well-muscled and quite noble looking, with not a hint of the animal or the monster about him at all. Like Thomas Stotthard, he too seems to have been primarily a painter of portraits, which might go some way towards explaining why he painted Satan as he did; he had no skill, perhaps, or at least interest or experience in drawing fantasy monsters, demons or devils.

Francisco Goya seems to have painted two images called

Witches Sabbath, though the one above is called that, from 1797-98, while another is called, um,

Sabbath of the Witches. Both feature the devil as basically an anthropomorphic goat. That’s it: no human characteristics at all, just a goat standing and behaving as a man.

Again, I don’t know if it was intentional or accidental, but there’s a very popish look to Louis Boulanger’s 1828 work,

The Round of the Sabbath, which has the Devil (presumably) standing in the middle of and I guess officiating at a witches’ sabbath. He even has a crozier! That can’t be coincidence. Let’s see what I can find out about this guy. Well, not much on a general skim. Nothing about his religious leanings, though given that his father was a colonel in Napoleon’s Army, perhaps he had none. He was a great friend of Victor Hugo, but that doesn’t really help me. If the painting is meant to be a criticism of, or allusion to the power of the Pope and trying to tie him to evil via witches, then it works very well. If not, well, I don’t get it. I mean, why give the Devil - again, assuming it’s meant to be him, but I think it is - such a close resemblance to the Bishop of Rome?

In the very same year we have a far more traditional and accepted image of the Devil in Eugene Delacroix’s

Mephistopheles Flying Over the City, which I can only assume, given the title, is based on Goethe’s novel, which we will come to in due course. This Devil has the wings, the horns, the beard, the hairy legs (in fact, hair all over his body, a little like our blue friend from 1490 as envisaged by Fra Angelico) although it’s interesting to note that Delacroix has opted to provide his Devil - Mephistopheles - with wings more like those of the angels, or at least more like those of swans, in contrast to the bat-like ragged black ones favoured by Cornelis Galle I three hundred years ago. I guess he could be basing them on the description given by Goethe (I haven’t read

Faust, tried once, got bored) but he does agree with his fifteenth-century contemporary (or maybe with Goethe, or both) on the feet of the Devil, which are not cloven but again have claws or talons.

I find it interesting that in this depiction the Devil is looking behind him, as if being pursued, as if almost fearful; perhaps a representation of the idea of his always being hunted by the thought of what he did, how he Fell from Heaven? Or maybe he’s just seen something interesting. I also get a real impression of a sense of femininity about this figure; despite the beard, the shape of the body (though it lacks breasts or any female genitalia) just suggests a woman to me. Maybe it’s the way the creature has its hand raised, which reminds me of a female gesture. And once again, maybe it’s just my twisted mind, seeing things that aren’t there.

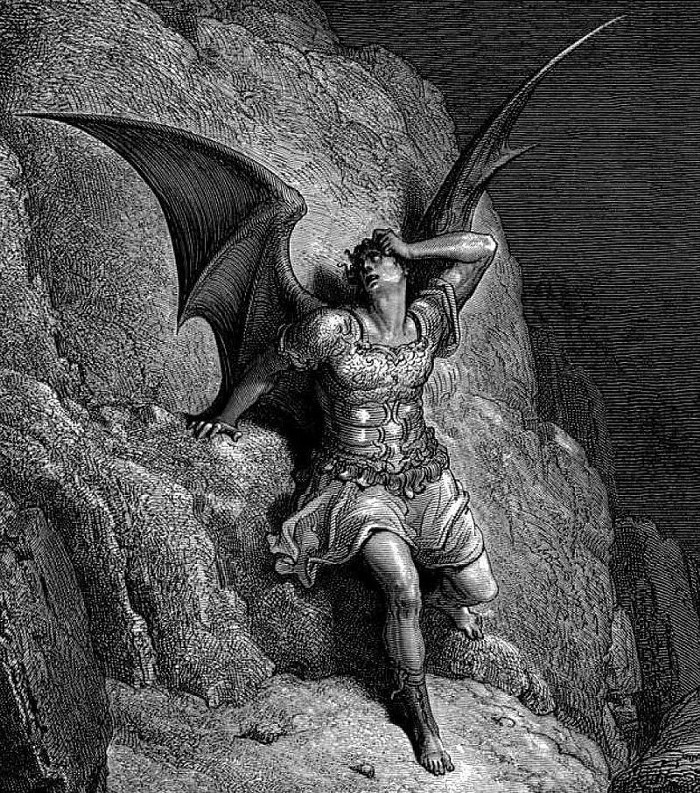

Ah but is it? Look at the picture above, created in 1866, and tell me this doesn’t look like a woman in distress, possibly being chased by someone and taking a breath, wondering how she’s going to give them the slip? It’s hardly classic devil imagery. I mean, yes, the wings, horns and kind of inhuman eyes are there, but the body, far from being covered in animal-like fur like our friend in the human soup from 1490 or even Delacroix’s slightly feminine Mephistopheles from four hundred years later, this is a far more human Devil. The fact that he is wearing what looks like the kind of thing a Roman legionnaire might have sported, essentially a tunic ending in what looks more like a skirt than anything, the bare legs and what could almost be breasts, adds to the feminine look. But what makes this one like a woman to me is the attitude almost of despair or panic; the hand pressed to the forehead in a gesture of fear, the way he’s shrinking back against the rock, as if trying to hide, the raised foot indicating flight or running, all speak to me of a Devil perhaps powerless and now on the run. Let me see what I can find out about this one.

Okay, well first, and interestingly, Gustav Doré was not only an artist but a comics artist, a sculptor and a caricaturist (well, you’d expect that if he drew comics, wouldn’t you?), a Frenchman who illustrated some famous works (including the most famous, the Bible) such as Poe’s

The Raven and Coleridge’s

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, as well as Milton’s Paradise Lost, the first book perhaps able to claim a sort of re-invention of Satan, or to put it in the words of Jagger and Richards, to attempt to gain sympathy for the Devil. This work though I can’t see among the list of his drawings, though the article does say

“his early paintings of religious and mythological subjects, some extremely large, now tend to be regarded as "grandiloquent and of little merit" at least according to the

Oxford Companion to Art. I’m not even sure if that is a painting though; from my very limited indeed knowledge of art I would hazard it’s an engraving? Anyway it doesn’t seem to have been regarded as very good by critics.

Ah. Looking a little further afield I find this is indeed from

Paradise Lost, and depicts Satan’s Fall from Heaven, which would, I suppose, explain why he’s looking pretty apprehensive, even scared. The person pursuing him - or perceived by him to be doing so - is no less than God, so I guess he

would be sh

itting himself. Doré also produced another painting (etching, lithograph, whatever) of him twenty years later, this time seated in council with all his demons in Hell, and he certainly looks more relaxed. He’s had time to settle in and get the place looking how he likes it, and he’s firmly established as the head honcho. If God was after him, he’s given up now and gone back to being praised by the angels, or whatever God does, and has left Satan to run things as he sees fit. So while it’s the same basic figure - hard really to get too many details as he’s drawn in the distance, all the demons clustered around him in the foreground - this one looks more in command, more a prince of Hell than a frightened exile fleeing Heaven.

Doré also painted one of Satan based on

The Inferno, where you can only see his top half as the rest of him is submerged in ice, and I have to say he looks pretty pissed off. Although he has the huge bat wings, the face is almost leonine, with thick curly hair and a thick beard, and so far as I can see, no real animal characteristics. If anything, he looks more like a figure out of Greek mythology, one of their gods or demigods. Minus the wings, of course. Dead giveaway, those wings.

I’m looking at this one by William Blake, produced sixty years before Doré’s efforts, and I have to admit it confuses me. First of all, there are three figures in his

Satan, Sin and Death: Satan Comes to the Gates of Hell (1808) and while one is clearly a woman, and therefore out of the running (if we take it that each of the figures represents one of the three in the title, then I guess she’s meant to be sin?), either of the other two figures could be him. One is a man, naked and without any of the usual demonic attributes - a distinct lack of horns, wings or even beard, and not a talon or claw in sight - Death maybe? Again, though, a very untraditional view of the Grim Reaper - while the other, whom I assume has the better claim to being Satan due to the presence of a crown on his head, seems to fade in and out of the figure as if there was some sort of superimposition going on. Either that, or the head at least is too far down on the body to be where a head usually is, and the arm seems to fade or not be completely drawn. All I can say is that if the figure on the right is Blake’s idea of Satan, then again he’s very human looking and not at all demonic.

His

Satan Calling Up His Legions, from about the same period, again shows quite a human figure, if surrounded by lurid red and yellow (obviously to represent Hell) while his later

Satan Smiting Job in the Sore Balls, sorry,

with Sore Boils does at least add wings, and bats wings at that, but still retains the basic, almost unsullied figure of a man, and quite a beautiful, angelic one too. Perhaps this is Blake’s attempt to show us what Satan has given up, what he was, and what he could have been had he obeyed God, with the wings there as a mark of what he has been changed into. Either way though, it’s hardly scary is it? William Hogarth’s even earlier (1735 - 1740) version of

Satan, Sin and Death seems to show The Devil as a kind of skeletal, dark figure (assuming he’s the one of the right) or else a warrior in that skirt-tunic again (if the one on the left) with red wings.