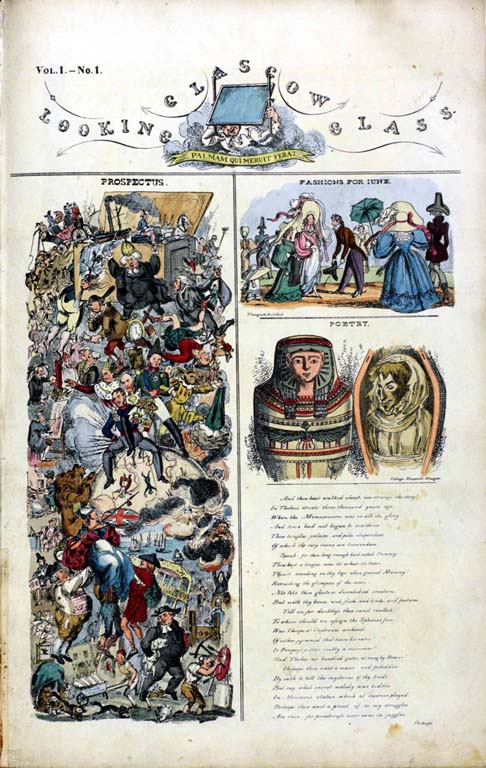

The Glasgow Looking Glass/The Northern Looking Glass (1825 - 1826)

The Glasgow Looking Glass/The Northern Looking Glass (1825 - 1826)

Though it lasted less than a year (in which time it was considered by the editors expedient to change the name)

The Glasgow Looking Glass holds a place in history as the very first publication in the world to feature only cartoons, which therefore makes it pretty much the first comics magazine. Launched by cartoonist James Heath, lithograph printer Thomas Hopkirk and his print manager, the interestingly-named John Watson on June 11 1825,

The Glasgow Looking Glass lampooned local and national politics, with a strong bias on those matters which might appeal more to a Scottish audience. Despite changing its name and trying to broaden its target audience a mere three months into its life, becoming the

Northern Looking Glass in August, the magazine failed to catch the public interest and sold poorly, folding before its one-year anniversary on April 3 1826.

Heath resurrected it four years later, with publisher Thomas McLean, under a new name:

McLean’s Monthly Sheet of Caricatures (sounds like

Herschel Krustofsky’s Clown-related Entertainment Show, doesn’t it?)

or The Looking Glass. This time the two aimed higher, looking to sell to a better class of reader, and were rewarded with a four-year run. For all its very limited success though, the (let’s just call it this okay)

Glasgow Looking Glass did start a custom later to be picked up by comics whole-heartedly, the serialisation of stories across several issues. This of course gives one the incentive, even the imperative to buy the next issue, lest they miss some important part of the story.

Heath began the rather dully-titled

Embarkation: Voyage of a Steam-boat from Glasgow to Liverpool, which did exactly what it said on the tin, but is notable for using self-referential comedy, as in it a passenger is drawn reading the magazine in which his strip is published, the

Glasgow Looking Glass. The second serialised story is

The Morbiade, more interesting at least as it’s about a riot and its consequences. The magazine is believed to have been the first comic to use the words “to be continued” at the end of the sequence, both as a marketing tool to sell the next issue and to assure readers the story was not over. Its most celebrated story though came in the fourth issue, with the

History of a Coat, perhaps the first cartoon to feature an inanimate object as the main character.

Macabre humour proliferated in

An Essay on Modern Medical Education, which shows students at a medical university mucking about, digging up corpses, stitching bodies back together, experimenting, watching skeletons walk through the corridors; all very darkly satirical, and maybe not without a note of truth in there somewhere. It is noted as being one of the most gruesome cartoons written at the time, quite graphic in the visceral depictions of body parts, experiments and even soldiers being sewn back up and sent back out onto the battlefield, surely some sort of comment on the pointless loss of life in war?

As the

Looking Glass closed its doors forever, across the Channel a French magazine was rising which would mirror it in some ways. I don’t know if it was the first French satirical magazine (probably not) but

La Caricature morale, politique et littéraire may very well have been the first magazine in that country to collect together political and moral cartoons. It did a whole lot better than its Scottish counterpart, running in total for thirteen years and constantly and ferociously lampooned the French king Louis Philippe. You know, given that the magazine could only be founded after relaxation of the French censorship laws following the July Revolution (what? I don’t know: pick up a history book! You want me to do everything for you?) it may just be possible that this was the first satirical magazine in France. Or not. Anyway it was a mixture of articles and cartoons, so not, I would think, an actual comic magazine like its Scottish contemporary, but it did give rise to one of the men who is acknowledged as all but a father of the comic.

But before we get to him, this is interesting. Despite the lax censorship referred to a moment ago, it seems

La Caricature, as it was usually known, pushed the king too much and was seized no less than twelve times, its editor thrown in jail and fined, and the magazine forced to close in 1835. Undaunted though, it was back open for business three years later, so my contention that it ran for thirteen years is incorrect - a thirteen-year period broken by a three-year one, so ten in all. Still very impressive. It seems William Makepeace Thackeray had something to say about the furore the magazine created:

Half-a-dozen poor artists on the one side, and his Majesty Louis-Philippe, his august family, and the numberless placemen and supporters of his monarchy, on the other.... The King of the French suffered so much, his ministers were so mercilessly ridiculed, his family and his own remarkable figure drawn with such odious and grotesque resemblance, in fanciful attitudes, circumstances, and disguises, so ludicrously mean, and so often appropriate, that the King was obliged to descend into the lists and battle his ridiculous enemies in form.

You know, I’m not sure whether he was siding with or against

La Caricature there, but he surely must have been thinking of his own king, George IV, who had been in a similar situation with the likes of Cruikshank and Gillray, though he had been less successful.

Honoré Daumier (1808 - 1879) was a sculptor and a painter, but in 1830 he joined the staff of

La Caricature, where a year later he was to draw his most famous and controversial cartoon, which depicted King Louis Philippe as a pear. Challenged on this, he drew a four-panel cartoon which showed the king transforming into a pear in stages. Eager to depose the hated monarch, the republicans grabbed the image and used it to mercilessly insult and depict the king on walls and in pamphlets. The cartoon,

Les Poires (the Pears, duh) has become one of the most iconic political satirical cartoons of all time. It says here.

But there was a darker, more serious side to his work too. In 1834 he drew a cartoon commemorating the bloody suppression of a protest, during which people were murdered in their own homes, including a baby killed. His sketch,

Massacre de la Rue Transnonain, 15 April 1834 so pissed the police off that they confiscated the original lithograph stone and a year later press freedom in France was abolished. You just have to love this guy though. Even thrown in prison for insulting the king, he continued to write articles and draw cartoons, telling everyone he was doing so “just to annoy the government”.

He attacked the corrupt legal system in

Le Gens de Justice, works so relevant still that they are often used by lawyers and judges and hung in courts of law, and he was a champion of the poor, like it seems many cartoonists of this era (and later) were, and continue to be. Yet you would have to think that few if any of these early cartoonists were paid well or made a living, as we have multiple reports of alcoholism, debt and poverty attending their lives. Daumier was no different; spent time in prison as mentioned but also struggled with debt and at one point had all his furniture confiscated to pay what he owed. You can’t help but think that the royal court may have had some hand in this - or at least tacitly approved it - given how much of a thorn he and his compatriots had become to Louis Philippe. Who would have thought merely drawing funny pictures could make you such an enemy of the state?

Still, like some of his peers he was not above (or below) mocking the ordinary man, if only gently. Similar to Gillray’s’

Elements of Skating and Newton’s

Sketches in a Shaving Shop, his

Les Baigneurs (1847) mocks people trying to swim. Perhaps harking a little towards Dickens’ Mr. Pickwick, his

'La Journée du Célibataire (1839) follows the adventures of a bachelor and was published as a text comic in a similar publication to

La Caricature,

La Charivari, while

Les Mésaventures de Mr. Gogo, (1838) appeared in yet another short-lived magazine.

There don’t seem to have been any happy endings for cartoonists or caricaturists or nascent comic artists around this time, and Daumier was another whose life ended badly, and pitiably. Sliding into financial ruin he lost his eyesight and was completely blind by 1873. Having refused the Légion d'Honneur three years previously, he died a pauper in 1878. After his death there were tributes from noted admirers. Famous novelist Charles Baudelaire named Daumier

"one of the most important men, not only of caricature, but also of modern art." His colleague Henry James said:

"It [presumably his art/caricature/cartooning] attained a certain simplification of the attitude or gesture which has an almost symbolic intensity. His persons represent only one thing, but they insist tremendously on that, and their expression of it abides with us."

Another caricaturist who worked at the same time as Daumier was Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard (1803 - 1847), who was usually known simply as J.J. Grandville, Jean-Jacques or just Grandville. His specialty was anthropomorphic animals, using the bodies of humans topped by animal heads, in an interesting style certainly. Whereas later illustrator Beatrix Potter would dress her animal characters, but retain their animal characteristics (squirrels would have bushy tails, paws and claws would still be used) Grandville seems to have obscured or omitted all animal traits below the neck, covering them in gentlemanly clothing or female dresses.

Unfortunately, he too came to a sad end, suffering badly from mental problems, and dying at the age of 44.

Brief mention must also be given to the already-nodded-at

La Charivari which, though not exclusively a comic magazine, did provide work for many of the more famous French cartoonists and illustrators, but more importantly must be one of the oldest and longest-running of its type, at least in its own county, as it ran well into the twentieth century, from 1832 - 1937, and was in fact the forerunner of the most famous of them all, the English magazine that dominated and tortured English and foreign politics all through the nineteenth century,

Punch.