Oh man! Can you believe it's been A YEAR AND A HALF since I last updated this? Let's sort that out now.

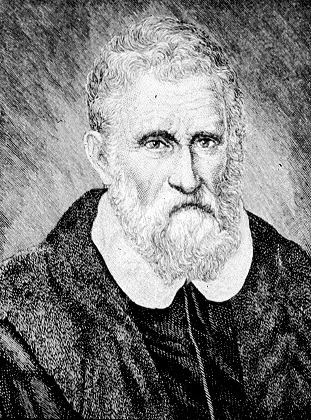

Let’s step away from the timeline now for a while, and concentrate on one of the great explorers of whom the title of this journal speaks. If any man can be said to have contributed to the creation of the map of the emerging world, certainly the eastern part of it, it was of course one Marco Polo. His exploits, his journeys and his traveller’s tales would enthrall his audience when he returned from Asia, the first* European to go there, and though he would not, unlike some of his fellow explorers, conquer the civilisations living there, or aid in their conquest, his name nevertheless resonates even now down the ages. Perhaps because of this lack of subjugation of nations, which was the usual result of such explorations (often, though not always, undertaken at the patronage and under the banner of different monarchs, who, like canny investors, wanted a return on their investment) Marco Polo is remembered principally as a traveller, an explorer and a teller of tales, and there is no animosity towards his explorations.

I: Like Father, Like Son

I: Like Father, Like Son

Marco Polo was born in 1254, into a time when Italy was still split into various kingdoms and states, most of which are now cities in the Italian republic. He was born in Venice, then called the Venetian Republic, a state which had been created six hundred years before his birth, and which would last another five hundred after. He was born into a mercantile trading family, but would not meet his father until he came of age at fifteen years old, as Niccolo Polo left on business while his wife was pregnant, and did not return until she was dead, and her son fifteen years of age. Marco grew up in a city, a country, a world indeed that firmly believed that the sun orbited the Earth, and that the latter was the centre of the universe. The brilliant astronomer Galileo Galilei would not be even born for another three hundred years, and religious superstition was well entrenched in Venetian daily life: it was even believed the entrance that led to Heaven, and the gateway to Hell, existed somewhere in the world, though given the state of thirteenth-century Italy, and especially Venice, it’s probably fair to assume none of its citizens expected to find either doorway where they lived. Well, possibly the second one.

In a time to soon, in historical terms, be ravaged by the worst plague mankind had ever suffered, as the Black Death raged across Europe in 1347, allowing the grip of the Church to tighten even more as the plague was seen as God’s curse on the world, Venice was not what you could call clean. Rats scurried to and fro with impunity, sanitation wasn’t even a vague idea in the heads of people, and medicine was, at best, rudimentary. Prayer was the order of the day, God was in charge, and the Church was all-powerful. Italians prayed no less than eight times a day, and even crossing the English Channel was considered a dangerous undertaking, not to be attempted lightly. Travel was slow; the fastest available mode was by horse, and you could expect a trip from Venice to Paris to eat up five weeks of your time. Ships, when they did launch, could be away for many years, and men could leave on a trading or exploration voyage as youths and return with grey beards. Marco Polo’s own travels would keep him away from home for twenty-four years, more than a third of the life expectancy at that time.

But Italy, like its earlier, more warlike predecessor, the Roman Empire, led the way, both in technology and in travel. Venetians saw travel as something normal, while the French, English and others feared and distrusted it, allowing Italy and its various city-states to become powerful and wealthy, and lead the world of mediaeval Europe. Italy, of course, would also become the centre for the great rebirth of ideas that would flourish in the sixteenth century, as art, literature, architecture and ideas all coalesced in the Renaissance. But far from being an idyllic centre of learning and art, a new cradle of civilisation, Italy was torn apart by war as city-state vied with city-state for power and control, and Venice was no exception. Her big enemy was Genoa, by coincidence the state from which another great explorer would rise, though his story would be vastly different to that of Marco Polo.

Venice would also become the banking centre of Europe, with some of the most advanced systems for finance in the western world, making sense of the often bewildering array of currencies and exchange rates, and helping in the process to fashion the city-state’s reputation and position as a leader in trade and commerce. It may also have been the first country, or as it were, state, to introduce marine insurance, mandatory there since 1253, one year before Marco Polo was born. Venice was so linked with trade and commerce that a little-known English playwright set some obscure play called

The Merchant of Venice there. Venetians also pioneered the then-original idea of partnering up with potential political enemies in the name of trade. Arabs, Jews, Turks, Greeks, even the savage Mongols, who could all be relied upon to attack Venice if the occasion demanded it and there was profit in it, became the trading partners of the city-state, old enmities and grievances set aside in the name of Mammon. Truly, as far as Venice was concerned, money talked, and made the world go around.

Considering the sight he would have seen of strange, foreign ships sailing into port from such far-flung places as Constantinople, Athens or Cairo, and also considering he had been born into a mercantile trading family, it’s no surprise that both the sea and the urge to explore were in Marco Polo’s blood from an early age. It will also come as no surprise at all that Venice boasted one of the best - and fastest - shipbuilding yards in Europe, turning out galleys at an incredible rate, at one point one new warship being launched every half hour. Marco’s father and uncle travelled east to Constantinople, the Crimea, Uzbekistan and Iraq, befriending the fierce Mongols and coming to know their ways, all against the explicit denunciations of these “tartars from Hell” by Pope Alexander IV, who had all but called for a Crusade against them. But Venetians seldom paid much attention to religious orthodoxy, and anyway, needs must. Forced out of Constantinople by civil and political unrest, the brothers Polo were constrained to travel through the Mongol Empire, unable as yet to return home. They were hardly going to upset the only people who could afford them shelter and guarantee them safety along the Silk Road.

Showing again pretty much contempt for the Pope’s views on the subject - and in fact, proving him to have been mistaken, or at best wildly misinformed - the Polo brothers met Kublai Khan, with whom Niccolo’s soon-to-be-famous son (of whose existence at this point he was still unaware) would spend over a fifth of his life. The Khan was known as the leader of the Mongols, great-grandson of the feared and legendary Genghis Khan, who had carved out an empire for himself across eastern Europe and Asia. Hyperbole proved to be just that, as the brothers remarked on Kublai’s manners, intelligence, interest in world affairs and courtesy. He was no savage, leading a cohort of demons bent on the destruction of Christianity, as Alexander would have it, but rather a man who wished to learn all he could about distant civilizations such as Europeans.

As a matter of fact, Kublai Khan astounded the Polos by insisting they be his ambassadors to the western lands, and particularly to the Pope, with an offer of an exchange of views and a discussion between his and their holy men of the nature of religion, with the hope that perhaps the Mongols could, if not be converted to Christianity, at least have it as an option. Not quite the sort of thing a “king of devils” would propose, and the Polos were somewhat overwhelmed at the scale and importance of the task with which they were entrusted, but unable to refuse. Apart from anything else, Kublai Khan guaranteed them his personal promise of protection so that they could return to their own country unscathed. Having faced many perils along the Silk Road on the outward journey, this was an undertaking they could not afford to pass up.

The apparent callous disregard with which Niccolo Polo essentially deserted his wife in order to embark on a trading mission with his brother shows how attitudes towards women were in thirteenth-century Italy. They were considered of no importance and of no use, other than for bearing sons, and were given no say in anything. To some extent, and given that slavery was certainly an accepted facet of life in Europe at this time, they could be considered slaves. They had no rights, nobody - especially their husbands - cared how they felt or what they thought, and it’s entirely possible (though you would like to think unlikely) that Niccolo just decided one day to head off to Constantinople with his bro and never even said anything to his wife. It’s certainly possible that he neither knew nor cared that she was pregnant. Whether he expressed any sorrow or guilt on his return to find her passed away is not recorded, but again it’s easy to think he greeted both this, and the news that he now had a son, with something of a typical Italian shrug. In point of fact, he quickly remarried and doesn’t seem to have had much interest in getting to know his estranged son.

But the Polo brothers’ mission had fallen foul of the death of the then-current Pope, Clement IV, and as usual, the election of his successor went on. And on. And on. So long, indeed, that they had to say

arrivedurchi , leaving Acre, in the Holy Land, where they had met the Papal Legate, Teobaldo of Piacenza, and returned finally to Venice in 1269. Here they waited for a further two years (!) before deciding they may as well head back to Acre and see who the new pope was. This time they would bring Niccolo’s now-seventeen-year-old son with them, intending to take him to see the Khan. Again, no mention is made of Niccolo’s new (and almost immediately pregnant - well, he was Italian!) wife, or what she thought about her husband fu

cking off to Asia again.