|

Born to be mild

Join Date: Oct 2008

Location: 404 Not Found

Posts: 26,996

|

I: Sketches in the fog

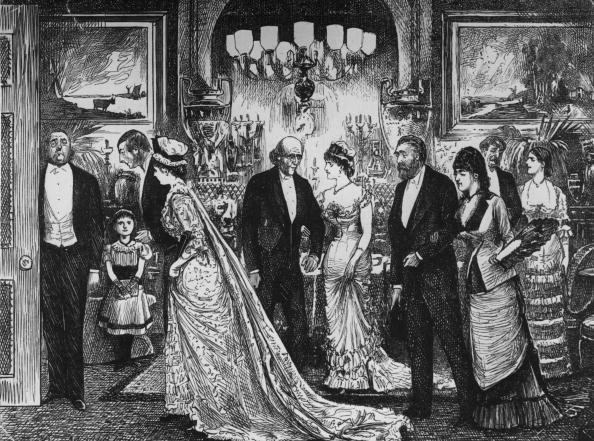

With their arrival in London the Dickens family increased again, Elizabeth’s fourth child born in 1816, Letitia Mary. Charles was now four years old, and beginning to form impressions of the world around him. Though he maintained he had memories from age two, they are rather vague and a little confused, such as his supposed recollection of a New Year’s (Eve?) Party where everyone seemed to be frozen in time:

“New Year's Day. What Party can that have been, and what New Year's Day can that have been, which first rooted the phrase, 'A New Year's Day Party,' in my mind? So far back do my recollections of childhood extend, that I have a vivid remembrance of the sensation of being carried down-stairs in a woman's arms, and holding tight to her, in the terror of seeing the steep perspective below. Hence, I may have been carried into this Party, for anything I know; but, somehow or other, I most certainly got there, and was in a doorway looking on; and in that look a New Year's Party revealed itself to me, as a very long row of ladies and gentlemen sitting against a wall, all drinking at once out of little glass cups with handles, like custard-cups.

What can this Party have been! I am afraid it must have been a dull one, but I know it came off. Where can this Party have been! I have not the faintest notion where, but I am absolutely certain it was somewhere. Why the company should all have been drinking at once, and especially why they should all have been drinking out of custard-cups, are points of fact over which the Waters of Oblivion have long rolled. I doubt if they can have been drinking the Old Year out and the New One in, because they were not at supper and had no table before them. There was no speech-making, no quick movement and change of action, no demonstration of any kind. They were all sitting in a long row against the wall - very like my first idea of the good people in Heaven, as I derived it from a wretched picture in a Prayer-book - and they had all got their heads a little thrown back, and were all drinking at once.

It is possible enough that I, the baby, may have been caught up out of bed to have a peep at the company, and that the company may happen to have been thus occupied for the flash and space of a moment only. But, it has always seemed to me as if I looked at them for a long time - hours - during which they did nothing else; and to this present time, a casual mention in my hearing, of a Party on a New Year's Day, always revives that picture.

His first proper memory of a person though (at least, the first he speaks of) comes at this time, when the family have moved to London, and he is being read to by his grandmother, Elizabeth’s mother, also called Elizabeth. Her stories are not of the fluffy bunny happy ever after type you would expect an ageing dame to regale her grandchild with, but tales of macabre terror and horror, calculated to chill the blood, and no doubt firing, if only subconsciously, the waking imagination of the young boy in that direction.

“My first impressions of an Inn, dated from the Nursery; consequently, I went back to the Nursery for a starting-point, and found myself at the knee of a sallow woman with a fishy eye, an aquiline nose, and a green gown, whose speciality was a dismal narrative of a landlord by the roadside, whose visitors unaccountably disappeared, for many years, until it was discovered that the pursuit of his life had been to convert them into pies . . . I had no sooner disposed of this criminal than there started up another of the same period, whose profession was, originally, housebreaking; in the pursuit of which art he had his right ear chopped off one night as he was burglariously getting in at a window, by a brave and lovely servant-maid (whom the aquiline-nosed woman, though not at all answering the description, always mysteriously implied to be herself).

After several years, this brave and lovely servantmaid was married to the landlord of a country Inn: which landlord had this remarkable characteristic, that he always wore a silk nightcap, and never would, on any consideration, take it off. At last, one night, when he was fast asleep, the brave and lovely woman lifted up his silk nightcap on the right side, and found that he had no ear there; upon which, she sagaciously perceived that he was the clipped housebreaker, who had married her with the intention of putting her to death. She immediately heated the poker and terminated his career, for which she was taken to King George upon his throne, and received the compliments of royalty on her great discretion and valour.

This same narrator, who had a Ghoulish pleasure, I have long been persuaded, in terrifying me to the utmost confines of my reason, had another authentic anecdote within her own experience, founded, I now believe, upon Raymond and Agnes or the Bleeding Nun. She said it happened to her brother-in-law, who was immensely rich- which my father was not; and immensely tall - which my father was not. It was always a point with this Ghoule to present my dearest relations and friends to my youthful mind, under circumstances of disparaging contrast.”

This account is written in 1855, for a compilation of ghost stories called The Holly Tree Inn, so Dickens would have had plenty of time to remember and refine his experiences at his grandmother’s knee, but the fact that he even remembers in such detail at such a tender age is pretty remarkable, and shows even then the kind of man he would grow into, a keen observer of humanity and of his surroundings, a man who completely exemplified the old adage, a writer writes always. I seriously doubt, had he for some reason really tried to, that he could have not written. It was just in his blood, it was part of him; it was his life.

This second description gives us a little more insight into the fearful woman whom he did not even recognise at the time as his dread grandmother, and whom in fairness it can’t be absolutely confirmed was that person, though various biographers agree the chances are that it was:

I remember to have been taken, upon a New Year's Day, to the

Bazaar in Soho Square, London, to have a present bought for

me. A distinct impression yet lingers in my soul that a grim and

unsympathetic old personage of the female gender, flavoured

with musty dry lavender, dressed in black crape, and wearing a

pocket in which something clinked at my ear as we went along,

conducted me on this occasion to the World of Toys. I remember

to have been incidentally escorted a little way down some

conveniently retired street diverging from Oxford Street, for the

purpose of being shaken; and nothing has ever slaked the

burning thirst for vengeance awakened in me by this female's

manner of insisting upon wiping my nose herself (I had a cold

and a pocket-handkerchief), on the screw principle. For many

years I was unable to excogitate the reason why she should

have undertaken to make me a present. In the exercise of a

something bad in her youth, and that she took me out as an act

of expiation.

Nearly lifted off my legs by this adamantine woman's grasp

of my glove (another fearful invention of those dark ages - a

muffler, and fastened at the wrist like a handcuff), I was haled

through the Bazaar. My tender imagination (or conscience)

represented certain small apartments in corners, resembling

wooden cages, wherein I have since seen reason to suppose

that ladies' collars and the like are tried on, as being, either

dark places of confinement for refractory youth, or dens in

which the lions were kept who fattened on boys who said they

didn't care. Suffering tremendous terrors from the vicinity of

these avenging mysteries, I was put before the expanse of toys,

apparently about a hundred and twenty acres in extent, and

was asked what I would have to the value of half-a-crown?

Having first selected every object at half-a-guinea, and then

staked all the aspirations of my nature on every object at five

shillings, I hit, as a last resource, upon a Harlequin's Wand -

painted particoloured, like the Harlequin himself.

Although of a highly hopeful and imaginative temperament,

I had no fond belief that the possession of this talisman would

enable me to change Mrs. Pipchin at my side into anything

agreeable. When I tried the effect of the wand upon her, behind

her bonnet, it was rather as a desperate experiment founded on

the conviction that she could change into nothing worse, than

with any latent hope that she would change into something

better. Howbeit, I clung to the delusion that when I got home I

should do something magical with this wand; and I did not

resign all hope of it until I had, by many trials, proved the

wand's total incapacity. It had no effect on the staring obstinacy

of a rocking-horse; it produced no live Clown out of the hot

beefsteak-pie at dinner; it could not even influence the minds of

my honoured parents to the extent of suggesting the decency

and propriety of their giving me an invitation to sit up at

Supper.”

The interesting word here - apart from the colourful description and exceptionally affecting picture of the terror a tiny child feels when taken to a place meant to be fun, but which is turned into a dark, forbidding realm of unseen and unspoken horrors when escorted there by a figure of dread, is his appellation of “Mrs. Pipchin” for the dark, mysterious figure, affording her the name of the cantankerous, cruel and spiteful keeper of a boarding house in Blackpool who would feature so heavily in the fortunes of poor young Paul Dombey Jr. in his Dombey and Son, and later come to represent a figure of opposition and an enemy to Mrs. Dombey. Of course, here Dickens is recounting as an adult, and can reference the character, but the point is that Elizabeth Dickens Sr. seems to have had so powerful an effect upon him that he remembered the experience when he was writing the novel, and looked back to those terrified days and that awful, at the time anonymous figure for inspiration.

There doesn’t seem to be all that much recorded about the Dickenses’ time in London, and in fact they only stayed there for two years before, as the Napoleonic Wars came to an end in victory for Britain, and navy work began to dry up, John was moved again, this time south to Kent, first to Sheerness for a few weeks but then to Chatham a few weeks later. Nevertheless, while at the former the Dickens family are said to have lived next door to the Sheerness Theatre, and it can hardly have escaped their attention and attendance, helping to further fire the imagination of the now five-year-old Charles and kindle his love of acting, plays and music, and of course, of writing. On moving to the larger, more bustling Chatham, also in the county of Kent, Charles and his family were introduced to a lively town bursting with interest, and made the subject of one of the many excursions undertaken by the title character and his friends in Charles’ first novel, The Pickwick Papers.

Another world was opening itself to the young boy, a world he had until then not really been aware of, but which was to drive and inform his life up until his death, and make him a famous and legendary figure long after he was dust. Charles began to learn to read, and with the help of his mother progressed to tackling the novels of DeFoe, Fielding and Goldsmith, as well as lighter, more fanciful fare such as The Arabian Nights, many of which would find their way into his own writings, in particular the latter in his recollections of Ebenezer Scrooge’s past as shown to him by the first spirit as the boy sits alone in the school at Christmas, with all his friends gone home for the holidays.

Charles had also begun to make his first friends, these being George and Lucy, the children of the neighbouring plumber, Mr. Stroughill, and inevitably, as a boy of five years faced with a pretty young girl, Charles fell in love with Lucy. He and his siblings and friends would also put on performances at this time, plays and comedies and farces, with all the seriousness and attention to detail as if they were to be played on the stage at the Royal Theatre, Charles giving the home-made amateur production as much attention as he would later afford his own professional writing. However all was not happiness in his world, and Charles had at this time begun to be assailed by pains and spasms in his side, which prevented him from being able to join in on the more boisterous games played by his friends and the local children, and being reduced to watching - and no doubt, observing - them as he lay on the grass, almost always with a book in his hand.

Performances of their little comic operas soon progressed to the small stage of the local tavern, the Mitre, where he and Fanny would sing and dance, their father having befriended the owner and their act no doubt drawing amused and admiring punters to the place to spend their money. Fanny outdid Charles in everything, being older and more versed in music and singing, but trips to the theatre and twice to London to see the great clown Grimaldi no doubt sent her brother looking in a different direction, that of authorship of plays. At eight years old, he wrote his first play, Misnar, the Sultan of India. No copies survive. His love of ships and the sea was heightened and helped when his father would take both he and Fanny aboard the Navy yacht named for the town, and they would see the workings of sailors as well as feel the deck roll and pitch beneath their young feet, smell the sea air and learn all about shipcraft.

But the dark spectre of John Dickens’ borrowings persisted and grew. While his friends the Newnhams, from whom he borrowed but as usual never repaid, did not seem to mind, even keeping in touch when the family moved away (with the debt, of course, still owing), Elizabeth’s brother was not so forgiving. Well, his new brother-in-law had stood, at Dickens’ request, guarantor and essentially borrowed a large sum - £200 - on behalf of the man, who then failed as ever to make the payments, leaving Thomas Barrow on the hook for even more than he had guaranteed. Thomas was so angry he cut off all communications with John. Debt would continue to control and all but ruin John Dickens’ life, and that of his family, ending for him - and them - in the cold, uncaring stone walls of a debtors’ prison.

__________________

Trollheart: Signature-free since April 2018

|