The Rights of (Catholic Irish) Man: Moves Towards Acceptance and Recognition

We’ve heard how much of an underclass Irish Catholics had become from the time Henry VIII established the Church of England and became an implacable enemy of the Pope, and more specifically from James II’s plantation of Ulster with Protestants, and the rise of the Ascendancy. For almost three hundred years now, Catholics had struggled to gain recognition and representation, rights and standing in their own country, and had been more or less laughed at and reviled. Taking up arms had not forced the British government to capitulate, and in fact they had little to no intention of doing so, as their own population looked to them to keep the “papist menace” at bay, none more so than the ruling classes of Ulster, who, though in power, felt like a man on a rickety raft in the ocean as the sharks swarm around him, closing in. Ulster Protestants were more than aware that they still made up the minority in Ireland, and beyond the border to the south was teeming with Catholics, all just itching to do them in while they slept. They must be kept down, brutalised, deprived of their rights, and given no chance to assert any sort of authority or raise their voices in government circles. It was their paramount mission.

To the northeast, though, too, another arch-enemy of the papacy watched developments with disbelieving and angry eyes, as the first Catholic Relief Act, called the Papists Act, was passed in 1778. Scotland had occasionally been an ally with Ireland against England, and, too, had sided with France against the auld enemy, but Scotland was very much a Protestant country. It was here that John Calvin had begun preaching his version of Protestantism, very much opposed to the idea of Mary, Queen of Scots, a Catholic, deposing Queen Elizabeth, a Protestant monarch. Presbyterianism was big here too, and there were few Catholics. But for all that, even more than Northern Ireland today, Scotland rang with the cry of “No Popery!”

So when the Papists Act allowed, under certain conditions, Catholics to join the army and own land, Scottish jaws slavered with rage, Scottish eyes bulged with hatred, and Scottish people rose in unison against this betrayal of their religious tenets. The fear was that although the Act applied at the time only to England, it was expected to be visited on Scotland too, and they weren’t having that! In response, a minor riot broke out on October 18 1778 in Glasgow, where the house of a family of Catholics who were celebrating mass was attacked, the windows smashed, the occupants chased out and the house taken over. Hey, sounds like those “Old Firm” matches between Celtic and Rangers to me! It wasn’t exactly a Scottish

kristallnacht, but it was telling that no law enforcement intervened, and the riot was only broken up when the rioters got bored and staggered off home. It was the first such riot, and really more a small display of the prevailing public feeling than an actual riot.

But a real one was on the horizon.

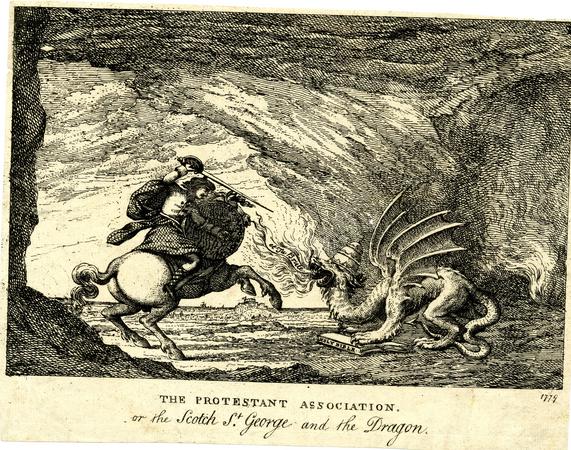

The Protestant Association

The Protestant Association

Created to combat the spread of the Catholic menace, the Protestant Association was basically a group of religious figures and politicians who fanned the flames of resentment against the papists, and scare-mongered for all they were worth. The Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge (SPCK) lobbied for the repeal of the Act, and tried to pressure the influential synod of Lothian and Tweedale, but Principal Robertson of Edinburgh University, where the synod was held, refused to be pushed, declaring that the SPOCK, sorry, SPCK was not going to force them to “deprive any person of his inheritance or subject them to civil penalties for conscience’s sake”. Frustrated, and afraid they would miss their chance to lobby parliament, which was soon to reconvene, the SPCK pulled in the support of the Committee for the Protestant Interest, also known as the Society of Friends of the Protestant Interest, to increase pressure on the synods, and later these two organisations merged to become the new Protestant Association.

With much distribution of inflammatory (and mostly inaccurate where not plain untrue) pamphlets, meetings and plenty of screaming and warnings, the Protestant Association quickly succeeded in its aim of turning the people of Scotland against the native Catholics, painting them as heretics and traitors who did not deserve any sort of tolerance, much less that shown in the Papist Acts. It was all but a call to holy war, and it spread like wildfire across Scotland. Town and borough councils quickly fell into line, petitions were organised and garnered thousands of signatures, and very soon a deep, entrenched resistance to any relief for Catholics rose right across the country. Some of the newspaper columns and pamphlets read disturbingly like something you might expect to see in a German newspaper around 1936.

“Have no dealings with them [Catholics]; neither buy from them nor sell them anything; neither borrow nor lend with them; give them no visits, nor receive any from them.”

“Let them [those against Popery] make lists of those within their bounds, containing their names, callings and places of abode, and publish it, that all men may know them.”

“Let each parish make a solemn resolution to drop all intercourse with papists, particularly bearing in mind that they will not in the future employ papists in any business whatsoever.”

“And that whosoever within their bounds acts contrary to this resolution shall be reputed a papist, and dealt with accordingly.”

Well, that’s nice and clear isn’t it? Sieg Heil, Jimmy, pass the jackboots! If you think senators and congressmen being intimidated by Qanon and Trump supporters is new, then listen to this extract from the account by Principal Robertson, denouncing the Protestant Association in the General Church of Scotland:

“I have been held out to an enraged mob, as the victim who next deserves to be sacrificed. My family has been disquieted; my house has been attacked; I have been threatened with pistols and daggers. I have been warned that I was watched in my going out and my coming home; the time has been set beyond which I was not to live, and for several weeks not a day passed on which I did not receive incendiary letters.”

One assumes that’s a metaphor, not that he was receiving actual bombs, but hey, put nothing past these guys. They were pissed, pissed as only those who hate and despise any dissenting voice can be pissed. They believed Robertson a Catholic-lover, and were more than likely ready to surround his house chanting “Hang Robertson! Hang Robertson!”

Yet for all the unrest and hateful rhetoric coming out of Glasgow, it was Scotland’s capital city that provided the first real spark for a full scale riot. Accusations of a house newly built being used as a Catholic chapel in defiance of the law in 1777 led to a fever of anti-papist sentiment which started as vague and random intimidation of Catholics on the streets of Edinburgh and which exploded into a full out attack on the home at the heart of their (imaginary) grievance, that of Father Hay, on January 30. Windows were broken and assistance refused from the Lord Provost, who even turned back offers of help from other quarters, giving tacit approval to the attacks.

And that was all the crowd, who swiftly became a mob of rioters, wanted to see.

February 2 saw the wholesale destruction of Catholic properties, their owners forced to flee, the authorities nowhere to be seen. The rioters returned the next day, declaring their intention to “compleat (sic) the destruction of every Catholic in the place, and of all others who had in any respect appeared favourable to their Bill.” Finally realising they could delay no longer, the city magistrates called in the army, and the enraged mob, trying to burn the home of their hated enemy Robertson, were turned back by an armed presence. With soldiers on the streets, the rioters drifted away, but they had achieved their objective. On February 6 it was announced that “the fears that had prompted such devastation had been justified” and the Relief Act was now “totally laid aside.” There would be no tolerance for Catholics, and the Protestants had won the day.

That was it for Edinburgh, as it was fun to terrorise unarmed Catholics (remember, the original Penal Laws forbade them owning or carrying weapons), scaring women and children, but the rioters were not about to go up against their own military, and while some, or many, of these men’s sympathies may have lain with the agitators, unlike today, they had sworn an oath to the King and would do their duty, regardless of personal opinion or affiliation. If not, they would likely have been court-martialled. But down the road in Glasgow…

Robert Bagnall was the most prosperous Catholic in the city, so naturally became the target for the anger of the mob that stormed through Glasgow on February 9. His crime, apparently, had been that he had “not been very moderate in his language or behaviour”, and his shop and house were burned while he and his family fled, sheltered by sympathetic Protestant friends. Once again, the authorities turned a very blind eye and nobody was prosecuted or arrested for the attacks. The government was humiliated to have been forced by the pressure of rowdy mobs and special interest groups to have to repeal the Papists Act, and voices within Parliament warned that what had happened in Scotland, and with no retribution whatever, in fact total success, could and most probably would be replicated over the border in England.

They were right.