By 1897, Tom Turpin of St. Louis had his “Harlem Rag” published. He is sometimes credited with being the first African-American to have a rag published. But Ernest Hogan seems to hold that record. The huge 250 lb+ Turpin is the first African-American to publish a rag with “Rag” in the title but that seems to be the extent of it. That’s not to short-change Turpin, he was known to have been playing that rag by 1892 and he opened the Rosebud Café in St. Louis which showcased a spate of ragtime talent. It was an exceedingly important watering hole for ragtime. “Harlem Rag” is a sweet, little piece and seems to have a bit of the Old West in it. Although I am trying to be concise, I would be remiss not have mentioned either it or Turpin:

Tom Turpin, Harlem Rag - Two Step (1897) - YouTube

By 1897, Scott Joplin came on the ragtime scene. Born in northern Texas about 1867 or so, Joplin showed musical talent at an early age. His mother, Florence, offered to perform chores for free to a white woman in town if she would allow Scott to practice on her fine grand piano. The woman agreed and listened to the boy play. She told some of her friends about the child prodigy and eventually word to go Julius Weiss, a German music teacher in town. He took Joplin under his wing and taught him music theory, classical music and opera. Joplin in particular loved the operas of Wagner.

Joplin joined minstrel troupe around 1893 before leaving for St. Louis and Chicago. By 1894, he was playing cornet for the Queen City Cornet Band, an all-black marching band that was the first marching band to play rags. They also played the classics and opera pieces and it is believed Joplin studied these pieces to get ideas for his own compositions.

The Queen City Cornet Band of Missouri. This photo was taken sometime around 1896. Some say the man on the far right clutching the cornet is Scott Joplin. My opinion is that the man does indeed appear to be him although he is believed to have left the band before 1896. Then again, the photo could be misdated or Joplin may have still been in the band and the historians are simply wrong or the man isn’t Joplin. Without an intense study of the original photo (if it still exists) no one can say.

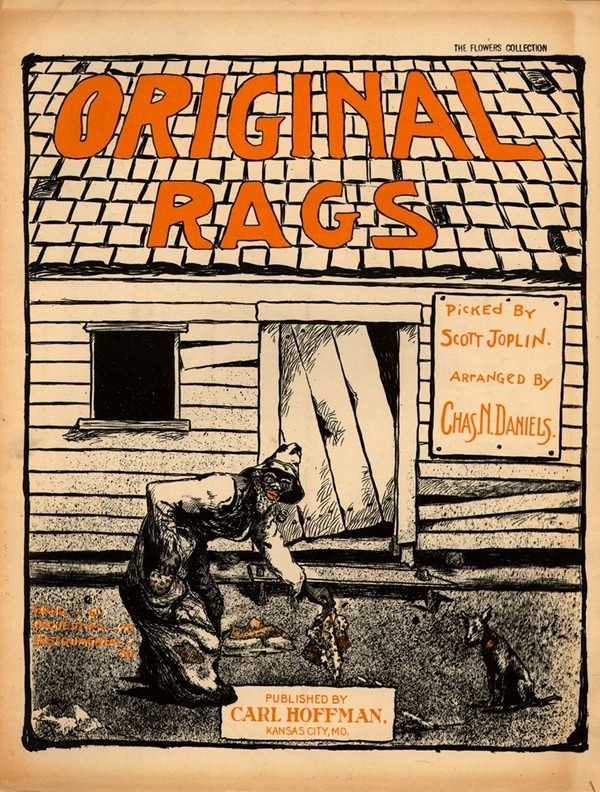

Joplin’s first published piece was “Original Rags” from 1897:

Scott Joplin - Original Rags - YouTube

Published by Carl Hoffman, Joplin didn’t get his due. He had to agree to let the house arranger, Charles N. Daniels, put his name on the piece as arranger despite having nothing to do with the arrangement. Some periodicals of the time that mentioned it also attributed the composition to Daniels and didn’t mention Joplin at all. The composition is clearly Joplin’s. His trademark style is all over it.

But Joplin’s big piece, the one he told friends would make him King of the Ragtimers, remained unpublished. He was turned away several times. Finally, a lawyer got Joplin in touch with the firm of John Stark & Sons of Sedalia, Missouri. Stark agreed to publish the piece as well as pay Joplin a royalty—an excellent deal which Joplin took. He had been working on this piece since at least 1894 when he first started playing parts of it for people. Now it was completed and published under the title “The Maple Leaf Rag.”

Maple Leaf Rag Played by Scott Joplin - YouTube

Maple Leaf Rag Played by Scott Joplin - YouTube

“The Maple Leaf Rag” piano roll. This sounds a bit fast. Joplin wrote on the sheet music that this piece was to be played slow, adding that “it is never correct to play ragtime fast.”

“Maple Leaf” became a gigantic hit, an enormously popular hit. By far, the biggest of the ragtime era. Joplin made a small fortune as did Stark & Sons. The country now knew the name of Scott Joplin. Whenever he showed up at a club (segregated, of course), the house pianist would break into “Maple Leaf” playing it very fast and embellishing it with all kinds of flourishes. Joplin always hated when they did that believing that they were trying to show him up (and they might have been) although he should have just taken it in stride. Even Jelly Roll Morton, a talented but hopeless braggart, who was a contemporary reverently referred to Joplin’s piece as “the perfect rag”—a praise he usually reserved only for his own compositions.

Joplin was a quiet, reserved man of high intelligence and perfect pitch. He spoke quietly in perfect, precise English. He hated the stereotype of black barnyard dialect. Those who met him found him personable although his conversation seemed to center almost entirely around music to the point where many thought him obsessed by it (nothing wrong with that). He never wrote at the piano but instead rode trains through the Missouri countryside holding manuscript paper and pencil and would start jotting down ideas as they came to him. He detested coon songs and said so in print but he seemed to be a man of few letters. We have little personal correspondence of Joplin so his views and aspirations remain somewhat of a mystery to us although he appears to have been perfectly literate. He was married once but his first (and only) child died in infancy and his marriage fell apart.

But Joplin had a dream and that was to turn ragtime into an art form. He planned to do this by bringing large helpings of classical music into the genre. He was not alone in this endeavor. Many of the black ragtime musicians were writing complex rags—heavy rags as they are called. Whites often went for the more pratfall rags or light rags. The money was in light rags and there were many excellent light rags and black musicians wrote and played many but they were also determined to turn ragtime into serious music and Joplin spearheaded this drive. In fact, he came to refer to his rags as “American Negro Classical Music.”